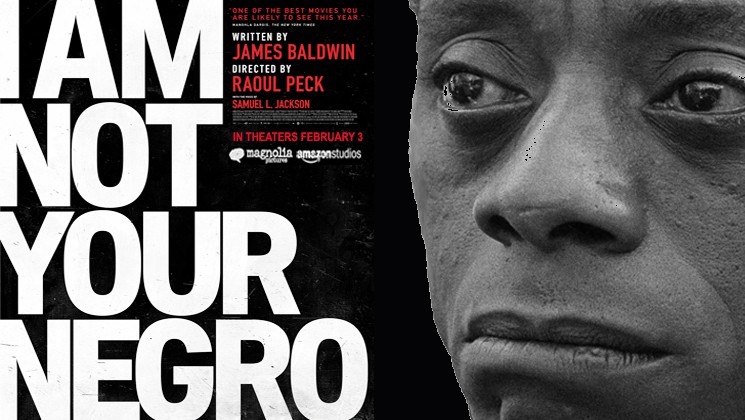

The new documentary about literary intellectual James Baldwin called “I Am Not Your Negro” reflects mainly on his friendship with three assassinated black leaders, MLK, Malcolm X and Medger Evers. Baldwin’s comments on race during his mid 20th century life are juxtaposed onto contemporary American 21st century racial relations.

This juxtaposition provides a grim picture somewhat at odds with Baldwin’s professed optimism. “I can’t be a pessimist because I’m alive,” he said. “I’m forced to be an optimist.” But the film has little room for hope, stressing racial sins without offering redemption. Baldwin died in 1987, so we can’t know with certainty what his current analysis would be.

A prominent novelist and erudite social commentator during the Civil Right Movement, Baldwin mixed easily with white and black celebrities of the 1950s and 1960s. Clips of his television appearances from that era are captivating. One clip shows his triumphant appearance before the Oxford Union in Britain but sadly omits his debate opposite, William F. Buckley. Baldwin, a spellbinding raconteur and polemicist, was overwhelmingly voted the winner.

In his words narrated for the film from an uncompleted manuscript, Baldwin contrasts his own lack of Christian confidence with MLK’s faith and his own lack of anti-white fervor with Malcolm X’s fiery racial rhetoric. Raised partly by an abusive preacher step father, Baldwin briefly himself became a teenage Pentecostal preacher before losing his faith. The film mostly omits his spiritual bio but notes his rejection of Christianity, seeing both black and white churches as hypocritical.

Only once mentioned in the film is Baldwin’s fairly open homosexuality, which made his sometimes sexually charged novels controversial. Fearing scandal, black civil rights leaders, including MLK, kept some distance from him. Robert Kennedy reportedly derided Baldwin as Martin Luther Queen. Apparently Baldwin’s own career was largely unaffected, despite an extensive FBI file. He spent much of his adulthood living in France, hosting entertainers, writers and fellow public intellectuals, white and black, American and European.

Citing his early mentorship by a white woman teacher, Baldwin rejected animosity against whites even as his literature and commentary focused on white racism. The film includes his critique of iconic Hollywood productions that reflected racial injustice and the inability of American whites to acknowledge their past and current prejudice. At one point, a circa 1960 fluffy scene of Doris Day is contrasted with the photo of a lynched black man from decades before. Non Hollywood news footage shows angry white demonstrators, some flashing swastikas, protesting integration.

Baldwin’s commentary of 50 years ago is backdropped against recent scenes of high profile police shootings, as in Ferguson, and of white politicians insincerely expressing regrets. The obvious implication is that American racial injustice perseveres, unabated. Baldwin’s reluctant optimism is recalled but not vindicated.

Likely at odds with Baldwin’s purposes, which arguably never entirely escaped the Christian faith of his youth, the film unapologetically adopts our current era’s morose and despairing assumptions. The exaltation of grievance and victimhood does not allow for atonement or meaningful progresss.

Baldwin seemed to anticipate some form of social salvation through repentance. MLK of course was more confident in his Christian expectation that righteousness prevails. MLK also subscribed to the Puritan vision of a nation under divine scrutiny and judgment, for which divine mercy was available. This notion of American Covenant, which channeled political reforms by religious and not so religious alike across centuries, has been subsumed in recent public parlance by the bleak outlook of relentless identity politics.

The creator of “I Am Not Your Negro” is so focused on this bleak outlook that he almost completely overshadows the embers of hope that glimmered even in Baldwin’s more macabre reflections. Yet the embers still sparkle if viewers look closely.

No comments yet