This is Part 3 of a four part series. Here are links to Part 1 and Part 2.

IRD: Before we get ahead of ourselves, I want to ask something else about Davenant Trust. It’s not merely academic in scope, is it? You all are committed to a revitalization in the pews as well, correct? I mean, we’re living in an era of impoverished revivalism, relativism, apostasy, hyper-confessionalism, or dramatic pilgrimages to Rome and the East. Does the Reformation with its irenic champions actually have something good to offer people outside of academic and historic curiosity?

Dr. Brad Littlejohn: Absolutely. As part of my involvement in another organization while in Edinburgh, I helped organize a day-conference called “Addressing the Gap Between Professor, Pulpit, and Pew,” which I think aptly summarizes one of the things that the Davenant Trust is about. We live in an age of the radical democratization of theology. To be sure, your average Joe, be he or she generic non-denominational evangelical or even stubborn Reformed presbyterian, remains happily anchored in the practical, with little inclination, and little time to spare, for digging into or disputing about the intellectual underpinnings of his practice. But among those with any sort of bookish disposition, or even any fondness for debate, or for questioning, “Why do we do things this way? Could we do better?” the rise of the internet has facilitated the emergence of a vast class of amateur theologians, or perhaps we might say amateur theologizers. Of course, I am not about to offer clichéd elitist lamentations about this state of affairs, since obviously it has been in many ways a rich gift to the church, without which, indeed, I myself might never have pursued the advanced studies I did, and without which I would not have half of the friends I do.

However, the problem is that while it does not require very much special training or practice to offer fairly thoughtful theological opinions, it does take training and a great deal of time to become conversant with the history of theological traditions. And contrary to popular opinion, these are usually profoundly relevant to the pressing disputations that occupy us today. This includes such matters as how to serve the poor, what to think about our nation’s wars, what just exchange looks like—ethical questions of deep concern to myself and many of my generation. Lacking the insights of the past as we venture into such complex questions, we risk, at best, laboriously reinventing the wheel, and at worst, stumbling headlong down a path of reasoning that the tradition has already carefully investigated and signposted “Dead End.” So we want to encourage thoughtful young Christians in the pews and on the blogs to start learning to reason with the tradition on such questions.

Of course, the issue of conversions to Rome and the East is another big issue. Some of these happen among prominent intellectuals, to be sure, but probably the largest proportion comes from this intermediate class of “amateur theologizers,” who know enough to ask a lot of the right questions, but not enough to know that there are some compelling answers that have been offered. Lacking such compelling answers in their own churches, they prematurely determine that their Protestant tradition is bankrupt, and jump ship.

So we aim to provide people with some of those compelling answers. Thanks to the same digital revolution that has democratized the theological landscape, it is now easier than ever to get all sorts of robust intellectual resources into the hands of any Christians who want to read them, and that’s one of the things we’re out to do.

IRD: Do you think we have a sort of Protestant historical amnesia when it comes to differences in Roman Catholic theology and how it’s evolved since the 1500s?

Littlejohn: To be sure. I think for many of us, at least those who grew up in more confessionally-aware backgrounds, we started out with an inquisitorial bogeyman of arch-Tridentine Catholicism, the foil for all our good Protestant doctrines, and then went through the disorienting experience of encountering modern post-Vatican II Catholic theology. It seemed so much cooler, more cosmopolitan, more Protestant than what we’d been taught to expect, and so we asked, “What was the fuss all about? We should talk to these people. We should learn from these people.” For some the vertigo was sudden and intense enough that, aided and abetted by the likes of Flannery O’Connor, Evelyn Waugh, and John Henry Newman, they stumbled straight into Catholicism themselves, often lurching rapidly back behind Vatican II in their sympathies. Of course, the reality is that neither the Cardinal Carafa bogeyman or the winsome watered-down de Lubacian are accurate pictures of Catholic theology, which is in fact in a state of enormous flux and internal tension.

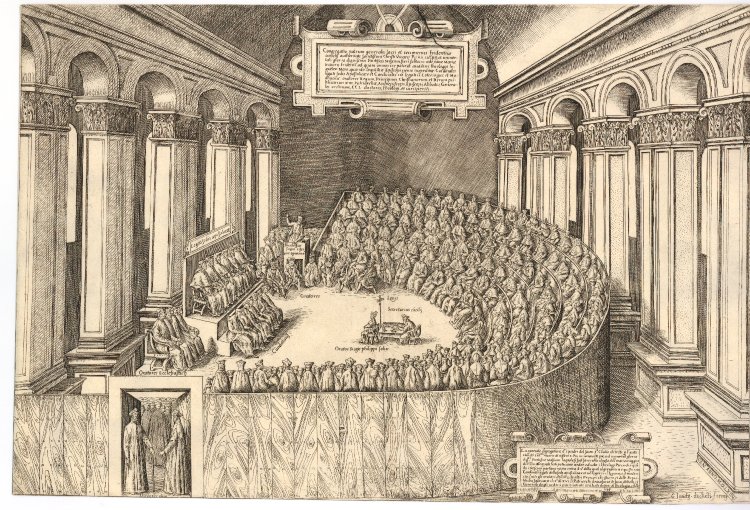

If we are to engage properly with it, and thus understand and articulate why we are Protestant, we need first to make a serious attempt to understand the contours of Catholicism on the eve of the Reformation and how these set the terms of Luther’s evolving protest. We must then come to grips with how Trent simultaneously embraced and repudiated many of the reforms being called for. There is of course immense 16th– and 17th-century polemical literature to guide us here; the difficulty is that sadly, a good deal of it does indulge in the sort of lurid bogeyman sketches that became the norm for many later generations, but there are also very learned, acute, and even irenic treatises penned by the Reformers themselves and their heirs that are too little read. Once we have a better sense of what was at stake then, we will be in a much better position to appraise the significance of the various changes in Catholic doctrine and practice since that time, and how they should and should not affect our prospects for ecumenical rapprochement.

No comments yet