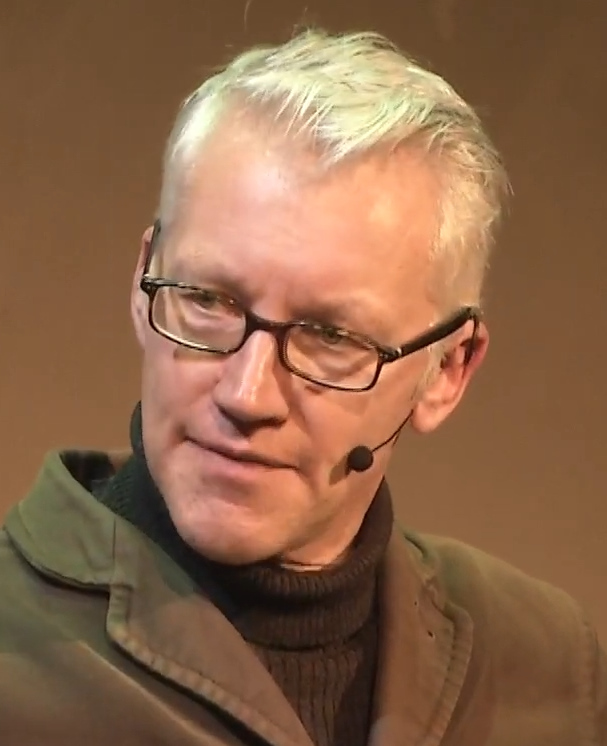

Tom Holland, a historian of empires, wrote Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World (2019) and challenged the predominant secular narrative of moral progress. In this telling of history, the modern world we know is the result of centuries of work towards emancipation from religious superstition. Although himself an atheist, Holland argues this progressive historiography fails to consider that our moral categories themselves are the result of Christian influence.

Holland recently discussed Dominion on an episode of the Ploughcast, part of Plough Quarterly published by the Anabaptist Bruderhof community. It was hosted by Susannah Black and Peter Momsen, editors of Plough.

The interview began with a discussion of the role of moral imperatives in the justification of empires. An empire, in contrast to a nation, is a body which unites disparate peoples into some kind of unity, whether it’s justified by “might makes right,” a religion or another ideology.

“Persia is the first empire that effectively moralizes its own imperialism,” says Holland. “So it sees the world in terms of good and evil, of light and darkness. And that obviously is a huge influence on Christianity, and indeed Islam. And there’s a tendency in the West to see ourselves as the heirs of Greece and of Athens, but I think we’re at least as much the heirs of Persia… the idea that simply because America is a democracy and because Athens was a democracy, therefore there’s a straight line of descent from the two is very much complicated by the fact that actually, it’s Persia that provides the model for Christian and Islamic imperialism.”

Though Holland is an atheist, he confessed that the final chapter of his book is “an acknowledgement that it’s ridiculous to imagine that I can stand outside. Because the central claim of the book is that the West is just completely Christian. That you don’t have to go to church or believe in God to be shaped by it so profoundly as, in effect, to be Christian. So to that extent, I would say I’m absolutely Christian because I think it’s impossible to be in the West and not to be shaped and influenced by it.”

But how did Christianity alter the preceding Roman and Greek worldview, which the West’s perspective also draws from? Holland illustrated the difference by looking to “the core symbol of Christianity… the cross” which “had important significance in the Roman imagination as an emblem of their power, and their authority to inflict torture… to suffer on the cross for the Romans is the worst possible death. It’s the most humiliating; it’s the most agonizing.

Holland continued: “And the humiliating character of the death is precisely what then serves to affirm the dignity of Rome as an imperial power and the master, as someone who can inflict this suffering on the slave. Christianity obviously radically, radically reconfigures that. And the idea that the cross can serve as an emblem of the triumph of the slave over the master or the victim over the victimizer or indeed the provincial over the imperialist is so destabilizing. But it’s hard to put into words just how profound a cultural upheaval it represents.”

Black described the “empire” created by the rise of Christianity as “an empire of the mind… although not a political empire, there is almost an invisible empire which I would say corresponds to something like what Christians think of as the Kingdom of God, that’s been permeating through the West over the course of Christianity’s rise.”

Holland then discussed the way that many of the social movements in America post-WWII, despite being outwardly secular, are in fact heavily laden with religious baggage. During the African-American Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and ‘60s, Martin Luther King, Jr. and other leaders utilized distinctively Christian rhetoric to advance their cause. But later movements for feminism, gay rights and other ideas of social justice have maintained the same Christian underpinning with different, ostensibly secular language.

“It seems to me that essentially the culture wars, arguments over theology, where one side isn’t recognizing the fact that actually it’s a theological argument because the fundamentals of antiracism, of gay rights, of Trans rights, of feminism are all rooted in the Christian assumption that the first shall be last and the last shall be first. The idea that it’s better to be the victim than the victimizer,” Holland reflected.

The conversation concluded with a discussion of philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, known for being the first philosopher to realize the inescapability of the Christian morality that permeated Europe. As European elites fancied themselves more and more secular, Nietzsche saw through the ruse that liberal-democratic values could ever function without Christian influence. His words continue to describe the progressive Left in America, which despite its apathy or hostility to Christianity, still depends upon it as an ungrateful heir.

Comment by td on November 18, 2021 at 9:27 pm

Poor, poor atheists. And the woke. The woke can’t see anything except through the prisms of race, slavery, and class. When can we just start calling them Marxists? Maybe they’re not economic Marxists, but they are definitely adherents to a Marxist worldview.

Comment by Newsflash on November 19, 2021 at 9:51 am

Wow, internet reports ‘Man bitten by dog.’

Thanks for the article. It’s nice to see that even atheistic academics are honest enough to see the reality in front of them once in a while.

Maybe next week we will hear that someone will say, ‘wow, traditional moral values are important to a functioning society, especially for the poor.’

Comment by David on November 19, 2021 at 4:12 pm

The question is whether Christianity was simply the most successful of the pagan mystery cults. Traditional Judaism rejected the notion of an afterlife and this is even mentioned in the Gospels. In his epic survey of European culture, “The Western Tradition,” Eugene Webber made the point that the chief characteristics of Roman-era mystery cults were life after death for members only and a ceremonial meal. To observant Jews, the idea of eating human flesh and blood even symbolically would have been disgusting. The magical nature of this was shown by the popularity of drawing curtains about the communion table during the consecration in the earlier centuries. This still survives in the Eastern Orthodox church with the iconostasis screen.

Christianity soon became polytheistic with a great mother goddess (Mary) and a host of demigods (saints), all the objects of worship. Indeed, some locally venerated saints in Europe predate Christianity. Then there was the adoration of relics. Kenneth Clark noted that one saint, martyred for refusing to sacrifice to idols, was represented by an idol herself. Of course, Protestants rejected many of these practices, though they were of long tradition.

Christianity is connected with feudalism, divine right monarchy, and indifference to slavery—matters rejected in modern times. It is difficult to say that morality is better in the West than in other places. Even the priests that traveled with Cortez in Mexico mentioned that the Aztecs had good morals, though they obviously rejected their religion. Are Christian morals actually better than those found in Buddhism, for example? Japan has lower crime rates than many Christian countries.

Comment by Barbara on November 19, 2021 at 9:48 pm

We certainly are still experiencing Friedrich Nietzsche’s influence in the West. Nietzsche’s book “God Is Dead,” is all about replacing Christianity with atheism and Islam.

Nietzsche believed that Christians are too weak to take over the world and run it from the top down, and to use the force necessary to bring totalitarianism back into Europe.

Comment by Barbara on November 20, 2021 at 5:06 pm

Hmm, I see I renamed Nietzsche’s book “The Antichrist,” by calling it “God Is Dead.” Anyway, Nietzsche’s anti-Christian influence in the world can even be seen in the liberal Christian denominations today with their rejection of right and wrong and a worldly idea of justice, instead of God’s justice, and in so many other ways. Nietzsche was for a totalitarian state and hated democracy. The liberal religious of today think like him, but use propaganda to get the common people to think they are on their side, when actually they are for top down government with real overlords and not Jesus as king.

Comment by Rev. Dr. Richard Allen Hyde on November 22, 2021 at 10:42 pm

Y’all need ti fix this paragraph:

The interview began with a discussion of the role of moral imperatives in the justification of empire. cultures and traditions while also professing a universal and borderless brotherhood of man. An empire, in contrast to a nation, is a body which unites disparate peoples into some kind of unity, whether it’s justified by “might makes right,” a religion or another ideology.