What does Gallup’s new survey showing fewer than half of Americans now self-identify as church members mean?

It means USA Christianity must prioritize what is now unfashionable: evangelism. The Church has many tasks but all are subordinate to sharing the Gospel.

This evangelistic task is not just a spiritual imperative for the Church. It’s a cultural, social and political imperative for the nation. Only revived religious institutions can counter polarization and political extremism while seeking social harmony based on a vision of divinely ordained human dignity for all.

Hyper individualism fueled by internet fantasies, “reality” tv, and faux online communities can only be displaced by revived congregations that are politically, racially and economically diverse. And while nondenominational churches are often strong engines for Gospel service, America needs revived denominations with sound ecclesiology and wider perspectives on social renewal.

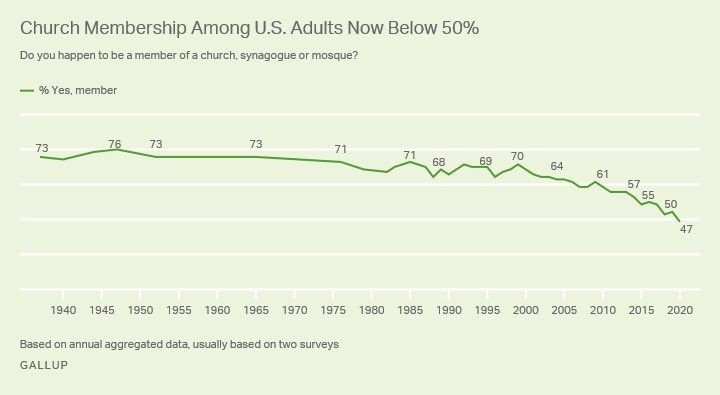

America is where it is today partly because once great denominations, both liberal and conservative, forgot their first task is to evangelize. Only 47% in Gallup’s new survey said they belong to a religious congregation, compared to over 70% from the 1930s to the 1980s.

It’s no great surprise, given that surveys show about one quarter of Americans now identify as religiously unaffiliated.

Gallup’s new survey shows over 70% of Americans still identify with a religious tradition, although apparently nearly a third of them don’t identify with any congregation.

The survey is about self-identification, not actual church statistics. Almost certainly, more people believe they are church members than actually are.

For example, the 2012 Yearbook of American and Canadian Churches counted nearly 160 million members of Christian denominations in America. Gallup found 61% of Americans identifying as religious congregational members about that time, equaling about 200 million. Even factoring in non-Christians and nondenominational Christians not captured by the Yearbook, self-identification clearly exceeds church data.

For historical context, it’s important to recall that 20th century church membership was higher than the 19th century. A 1986 study by Roger Finke and Rodney Stark from The Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion found that 14% of Americans in 1800 were church members. It was 26% by 1830 and by 1860 it was almost 39%. In 1890 it was 43%. By 1906 it was 50%. In 1916 it was almost 54%, and 58% in 1926.

The past was not always as religious as we imagine. The Second Great Awakening jumpstarted religion in the early 19th century. And, often helped by succeeding revivals, it kept climbing, as the historic Protestant denominations became more established, built great churches, started schools and publishing houses, and came to dominate much of American civic life.

Population growth and urbanization brought more people, previously isolated on the frontier or the countryside, into closer proximity to churches. The Catholic Church also became a growing force in the mid 19th century with waves of immigration from majority Catholic European countries.

Most Protestant historic denominations, having become “mainline,” began their 60-year decline in the early 1960s. Catholicism, although not numerically declining at the same rate, began declining as a share of population in recent years.

Evangelicalism, sometimes rooted in denominations, but increasingly nondenominational, began growing dramatically in the 1960s and continued until relatively recently. The largest Protestant and Evangelical denomination is the Southern Baptist Convention, which began declining about 15 years ago. Growing evangelical churches tend to be more Pentecostal and racially diverse, such as the Assemblies of God. Nondenominational churches are the fastest growing religious movement in America but their numbers are hard to quantify.

A 2015 Pew study found over 25% of Americans are Evangelical, nearly 15% are Mainline Protestant, 6.5% are black Protestant and nearly 21% are Catholic. Jews are nearly 2% and Muslims are 1%. The religiously unaffiliated are 23%, including 3% who are atheist and 4% agnostic, leaving over 16% as “nothing in particular.”

A survey released early this year, presumably conducted before the pandemic closed many churches, found 33% saying they attend church about weekly, and another 11% attending monthly. Nearly 30% said they never attend, and 25% said they seldom do. A 2019 Pew poll similarly found about 45% attend church monthly or more. Gallup surveys across decades found weekly church attendance from 37% to 39% in the 1940s, rising in the 1950s to 49%, falling to 38% in the 1990s, climbing again, and more recently declining.

Among all Americans, including the religiously, active denominational loyalties, like many historic denominations themselves, have plunged. A 2017 Gallup survey found that only 30% of Protestants identified with specific denominations, compared to 50% in 2000. Almost certainly that number has declined further. The fastest growing and largest congregations are almost all nondenominational.

Of course, we don’t know the pandemic’s full impact on religious participation. But very likely many churches that stayed closed for the last year, which is many if not most Mainline Protestants, will never recover. Some from those congregations may have moved to Evangelical or Catholic churches. And some will abandon regular physical church attendance altogether.

Religious belief among Americans continues with or without church affiliation or attendance. A 2018 Pew study found 56% professing belief in the God of the Bible. One third professed belief in a higher power they might call God. Ten percent rejected any higher power. A 2017 Gallup poll found 87% professing belief in God, not very different from year 2000. Sixty-four percent were “convinced” God exists.

Declines in church affiliation likely will further facilitate more esoteric and heterodox views of God and spirituality, with discordant political and social implications. Although a steady minority of Americans continue their church attendance, the nominal religionists who previously retained a denominational affiliation continue to detach from institutional religion.

Some Christians may celebrate the decline of nominal religion as clarifying. Now the true believers are more readily apparent! Supposedly. But even nominal religious affiliations at least connect the ambivalent and uncertain to a wider community of faith. The ongoing retreat of historic religious traditions in favor of spiritualized individualism is bad news for social harmony in America.

Christians and churches tempted to barricade themselves within their own silos against cultural adversity can’t successfully evangelize and can’t effectively serve wider society. Across four centuries American churches have nurtured the nation’s democracy and wider civil life by offering transcendent themes that override tribalism and hyper individualism. Democracy and society are now suffering from the churches’ retreat.

Only the churches’s full return to their evangelistic vocation will restore their vitality and renew America’s democracy.

Comment by David on March 31, 2021 at 10:52 am

It is refreshing to see an accurate account of religious belief in early America. Too often, people imagine it to be epitomized by the Pilgrim marching to church through the snow with a long gun in one hand and a Bible in the other.

A more sober observation is that of a 1750 visitor to Pennsylvania:

“Besides, there are many hundreds of adult persons who have not been and do not even wish to be baptized. There are many who think nothing of the sacraments and the Holy Bible, nor even of God and his word. Many do not even believe that there is a true God and devil, a heaven and a hell, salvation and damnation, a resurrection of the dead, a judgment and an eternal life; they believe that all one can see is natural.”

A major flaw of religious surveys is that people tend to give “nice” answers rather than truthful ones. There was a study carried by, I believe, the Catholic Diocese of Los Angeles. This found that their members claimed to attend services twice as often as they actually did and also donated half of what they said.

Even though large numbers of Americans live their lives as atheists with no religious practices whatsoever, they are very reluctant to call themselves that because of the prejudice against non believers. So, the surveys probably bode far worse for denominations than they appear.

Comment by Gary Bebop on March 31, 2021 at 8:19 pm

Mark, thanks for trying to trying to kick us awake and get us back into the field. Remember when Lyle Schaller was trying to light a fire under the church with his own statistical kindling? Did it work?

Comment by bob on April 2, 2021 at 6:07 pm

In a cuddle-Christian culture many join a church in order to have a church to stay away from. In nominal Christianity the controlling word is not the noun but the adjective “Nominal, i.e., in name only.” Consumer Christianity (now an annoyingly popular term) points to the celebrity Christ with his fans rather than the crucified Christ with his disciples. Such data, which has been available for some time in national trends, can give status quo complacency a bucket-of-ice water drenching and fresh incentive toward evangelism that actually…evangelizes, or a return to the inertia reflected in Hezekiah’s attitude when confronted by Isaiah toward the end of his reign about spiritual faults that would lead to disaster for his children. Outwardly the king burbled, “Gawd’s will be done,” while inwardly he shrugged, “Who cares, if the hammer falls on the kids but not me.” (2 Kings 20:19).

Comment by Rebecca on April 2, 2021 at 10:10 pm

Just to let you know, here are three books on colonial Christianity: “The Shaping of America, Volume 1, Atlantic America,” by D W Meinig, which gives the locations of Protestants before their trip to America, and their placement in America after being relocated. Another book is “Between Two Worlds,” by Malcolm Gaskill, about the English, especially the Puritans both in the Old and New World. Another book is “Sex in Middlesex,” which is about the laws on sex (adultery) both here and in Europe. And it also mentions that in order to become a member of a Puritan Church, you had to do a lot more than attend church on Sunday, although pew sitters were welcome. The Quakers and all the rest of the denominations had strict rules regarding church affiliation, and they excommunicated people for all sorts of things. Most of the people in America today, white or black cannot trace their ancestry to colonial days because their ancestors came later, and the religious tests were not as great for them.