Earlier articles focused how contemporary thought has tried to make the individual self sovereign over all reality, and the incoherent and disastrous consequences that this has had for law. Closely tied to this moral and legal catastrophe is the idea of moral relativism, which holds that there are no universal moral precepts.

Dominic Legge, Director of the Thomistic Institute and Assistant Professor in Dogmatic Theology at the Pontifical Faculty of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C. discussed moral relativism – which, as Pope Benedict XVI noted, is becoming the basis for dictatorship – from a Thomistic perspective, at George Mason University on March 2.

He began be saying that “the great sin of our age in the minds of many of our contemporaries is to be judgmental. You could even perhaps describe it as a kind of capital vice for postmodernity.” This postmodern moral precept is sustained by the belief that moral judgments are “arbitrary and subjective.” They cannot be known to be objectively true as proven facts are objectively true. Legge asked to what extent making a judgment is a sin, and how this relates to truth and law.

Legge observed that few people would actually say that no judgments should be made. Most people accept basic truths of mathematics and science. Legge asked how Thomists address the issue of making judgments.

A Thomist Analysis of Moral Judgments

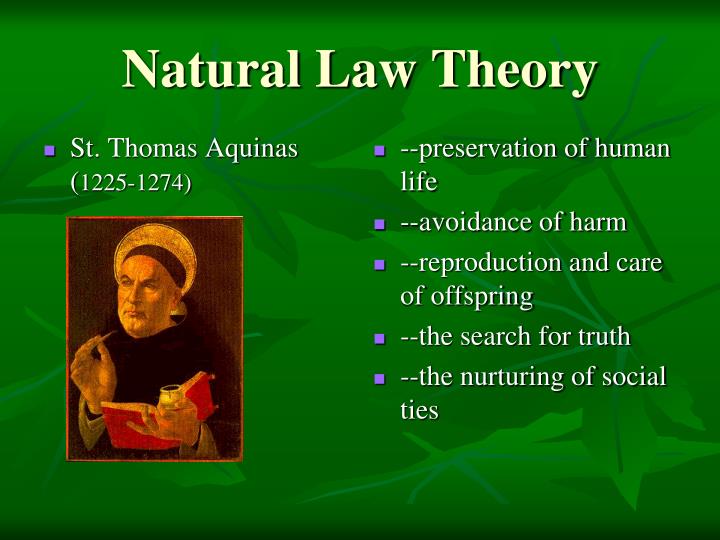

According to Aquinas – and behind him, Aristotle – the act of judging begins with “simple apprehension;” one is made aware of what a thing is. Secondly, there is “judgment,” which “involves joining and separating things.” A statement of what is true about something apprehended is a judgment. (“This dog is angry,” was given as an example). This for a Thomist, Legge said, “is one of the fundamental aspects of being a rational person.” This is not high philosophy, but “recognizing reality around us.” Natural science would not be possible without it.

The kind of “judgment” which is controversial in our day, however, is judgment about guilt. This is seen inescapably in the law. Fact and law are brought together “in what is technically called a judgment.” This is a final determination of what happened in a case, how the law applies to it, and a court order concerning what should happen as a result of the judgment.

Legge said that when people think of morality applying to law, they typically think of applying the prohibitions of traditional sexual morality to law. But really all laws have a moral basis. They at least claim to be enacted for a moral reason. Environmental regulations were given as an example; there are laws or regulations concerning the tolerable level are carbon emissions. Such a law may indeed be based on a factual assessment of what carbon emissions will do to the environment. But the assessment of what results are acceptable are assessments of value. People certainly make moral judgments about polluters.

Legge noted that penalties are imposed, and considered to be just, even if it is not to be expected that the person will commit the same crime again. A ninety year old murderer is still punished, even if it is not to be expected that he will ever kill again. This implies that the criminal act itself is believed to be wrong in itself. “Most laws contain implicit judgements,” Legge said. This supports what Aquinas says is “the essence of a moral judgement;” that “some things are good, and therefore to be protected or done, and other things are bad, and therefore to be avoided.”

Legge believes that Americans in particular regard the law “as a moral teacher.” One aspect of this is that people tend to regard what is legal as also being moral. The use of marijuana, for instance, is considered to be moral if it is legal.

The morality instructed by natural law, however, does not see a great difference between what a thing is, and “what is good for that being.” This is the judgment that Thomist/Aristotelian morality makes. But, Legge said, this morality applies only to actions, not to intentions. It is God who judges “the thoughts of the heart.” The “Christian virtue of charity” requires that we should love and “presume the best of our neighbors.” Love, however, involves a desire for the neighbor’s salvation, and thus his or her repentance.

The distinction between judging actions and intentions means that Thomists judge actions, not persons. This is distinct from the law of the state, which does sometimes judge intentions. In the private world, however, to judge what a person’s intentions are is to make “what Aquinas calls a rash judgment, which could be a sin.”

There is thus a difference between the objective moral status of an act, and the subjective guilt or innocence related to the act. Errors of fact may not be wrong (e.g., believing one owns a bag of candy that in fact belongs to a neighbor), errors of principle (e.g., that stealing is acceptable) are culpable.

The Relativist Alternative

Having described Thomist morality, Legge then evaluated the modern denial of morality (of which expressivism would be one variety). It holds that actions cannot be wrong in themselves. He observed that one can find moral relativism of different kinds on many college campuses. Among these are cultural relativism, in which morality is determined entirely by cultural forces – the culture into which one was born and raised. Historical relativism holds that morality depends entirely on the moral precepts “of a particular historical period.” Another form of relativism held in the legal profession is “legal positivism,” which says that morality is identical with whatever the law of the state says at a particular time.

What unites all doctrines of relativism is the denial of universal, unchanging moral precepts. This means that they have an “internal contradiction,” Legg said. They must make the claim that “there are no truths that hold always and everywhere is a truth that holds always and everywhere.” He believes that all forms of relativism “have this hiding in them somewhere if you look hard enough.”

Secondly, while there may be disagreement about certain topics (slavery, homosexuality, etc.), there is broad agreement on an essential morality (murder, theft, adultery, lying). Thirdly, the fact that certain cultures have rationalized things that are gravely wrong does not mean that there are no morally wrong things. Finally, relativism – as noted above – entails that “all moral claims are historically or culturally conditioned.” But if this were true, moral reform would not be possible. People challenge prevailing morality in the name of a higher morality. If this is not just another morality with equal value to what it is attacking, it can only be a claim to a universal morality.

Legge added a practical consideration, that “in practice, there are no moral relativists.” He said that moral relativism practically involves making a moral judgment against “judgmental” people, which is hypocritical. This, he believes, is becoming increasingly clear even to the general public in our day. It is unsurprising to Thomists, since Thomas taught “that moral judgments are judgements about what is good. And there is an unbreakable link between being and goodness … To make judgments is part of what it means to be rational.” People in fact “make judgments all the time.” However, some people “camouflage their judgments in the rhetoric of relativism.” Instead of this, Legge said, judgments should be brought “out into the open” and questioned in terms of the common good.

Legge quoted Pope John Paul II, who lived under both Nazism and communism as saying:

“totalitarianism arises out of a denial of truth in the objective sense. If there is no transcendent truth in obedience to which man achieves his full identity, there is no sure principle for guaranteeing just relations between people … Their self-interest as a class, group, or nation would inevitably set them in opposition to one another, if one does not acknowledge transcendent truth, then the force of power takes over, and each person tends to make full use of the means at his disposal in order to impose his own interests or his own opinion, with no regard for the right of others.”

Legge observed that denying truth results in a denial of democracy, which results in a denial of freedom. He believes that in this John Paul II was “prophetic.”

A free, democratic society must be based on truth and judgments flowing from it. The denial of truth results in what Pope Benedict XVI called “the dictatorship of relativism.” Legge said that “if you adopt relativism, you will be forced into a dynamic that is not governed by reason. And without rational discourse, there can only be appeals to ideology or to political power, but not appeals to the truth. There will still be judgments there, because that’s inevitable, but they will not be subjected to rational analysis. But they will be imposed by acts of will or by acts of power.” He quoted the words of Jesus to the contrary, “you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.”

A questioner asked how far absolute truth and morality can apply to particular opinions. Within a group of committed Christians, for instance, there might be different opinions about environmentalism. Legge responded that first we must concede that “there is an objective order of truth.” But “as you descend into the particulars, the moral truth of the matter is harder to discern, and it’s more subject to real disagreement.” The is the reason a political structure is important – to resolve conflict.

But Thomist thought does not leave all particulars to opinion and political arbitration. It attempts to derive both negative precepts (what we must not do, as the Ten Commandments specify) and positive precepts (what is required of us). The negative precepts are easier to derive than positive precepts. Understanding the practical meaning of “thou shalt not commit adultery” is easier than understanding the practical meaning of “love your neighbor.” The former is always wrong, whereas doing the best thing for your neighbor depends on many circumstances that vary with individuals.

Another questioner asked if it is not necessary to separate fact and value judgments in the interest of civil peace. Here Legge responded that the liberalism of the Enlightenment tended to bracket off questions of ultimate good, and focused instead on evils to be avoided. But Legge said that “in the end, it is not really possible to define what is bad without reference to what is good.” He cited abortion as an example. The question of whether an unborn child is a person cannot be “bracketed off,” with the claim of neutrality, because the law must take a stand on whether or not unborn children can be killed. If the decision is that they may be killed, the law has effectively declared that unborn children are not persons. Fact and value cannot be separated, Legge asserted, because being itself is good, and so the mere assertion of being carries with it a value judgment.

Another questioner asked if liberalism is compatible with Thomism. Integralists, he noted, claimed that the political order should explicitly recognize Christianity as correct, and mandate that the state act within its precepts. Legge said he does not believe that Thomism is necessarily incompatible with liberalism. However, rights should not be understood as absolute, individual rights based on moral autonomy, but rights as embedded in a “political order as oriented to the common good.”

Legge said that God “makes us good, first by the gift of being itself,” which we didn’t deserve. And then by his grace, which makes the individual good. The reason for God loving me is not so much me, as it is that God’s goodness and love.

Comment by Rebecca on March 13, 2021 at 11:54 am

When the movement to have America accept homosexuality began, it was decided that the legalization of homosexual marriage would get rid of the three serious objections to that life-style. Homosexuality used to be considered immoral, illegal, and insane. It used to be against the law for immoral people to get married, and homosexuality is immoral. It used to be that the marriage couple could not be insane, and homosexuality used to considered a mental illness. And, marriage was between one man and one woman in order to make it legal. This is an example of how people go about using the legal system to change the morals and judgments of society. Was it Marx who said we will use their rope to hang them?

Comment by Naomi P Wade on March 14, 2021 at 5:51 pm

The church cannot participate in this folly., It is still immoral, as other things are. We cannot put them in jail. They cannot be ostracized. But, they should not ask the church to help them in their wrong endeavors. It’s like a thief asking the minister to drive the car while he robs the bank. Common sense has got to be in this whole conversation. They have made a ‘choice’. They need to understand it is not the ‘choice’ of us all. They cannot direct all of our lives just to justify their own ‘choice’. It IS possible to love the person without loving &/or participating in what they do. The church has got to remain a vessel for the word of God & HIS truths. It does involve deep humility– the acceptance of people without mocking, without mistreatment. THEY have got to respect the ‘acceptance’ of the others view, also. Do not ask of others what you know they cannot do. IF they truly KNOW the living God– they would not need to make everyone else participate in this. They would have respect for the friendship/fellowship that must be involved. It is much bigger than just ‘accept all I do’ or else. Much deeper. There is always a need for ‘moral’ judgement. Every decision made is based on a necessary ‘judgement’. There cannot be law &/or order without ‘judgement’. God made them – man & woman. WE cannot change that.