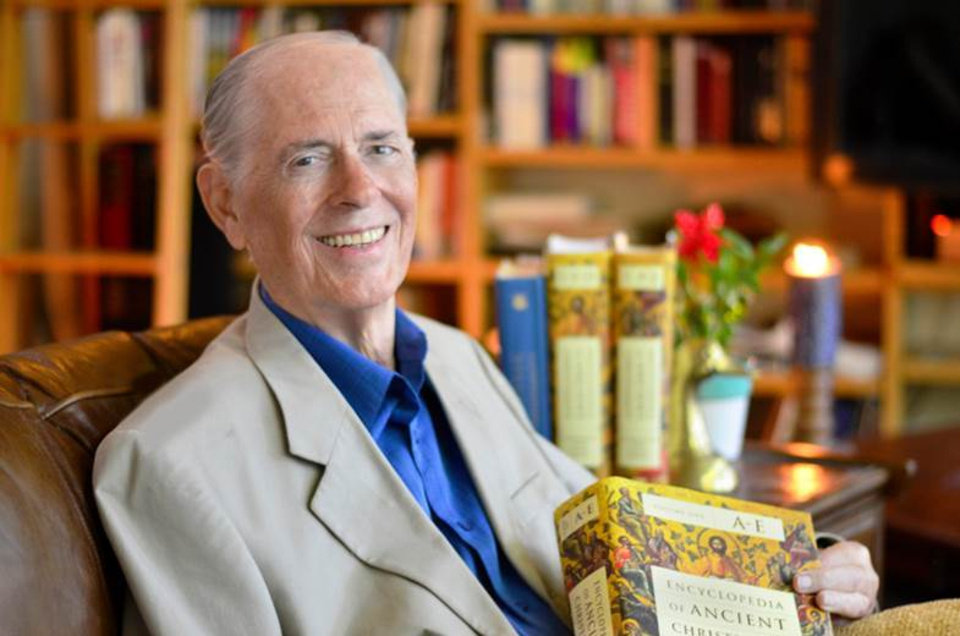

Editor’s Note: Below is the transcript of an interview with the late Dr. Thomas Oden from March 2006. He spoke with Institute on Religion & Democracy (IRD) President Mark Tooley and former IRD staff members Jim Tonkowich and Alan Wisdom. Dr. Oden, who helped to found IRD, passed away in December 2016. Dr. Oden is remembered as one of the most respected and best known theologians of Church renewal.

During the interview, Dr. Oden discussed his recently published book, ‘Turning Around the Mainline: How Renewal Movements Are Changing the Church’ (Barker Books, February 2006). He examined the roots of the Evangelical and orthodox renewal movements in the Mainline denominations, the major themes of these movements, and the concerns they faced, including property rights. His tone and his conclusions were positive and upbeat in spite of some difficulties.

IRD: Tom, in a nutshell, your new book, Turning around the Mainline: How Renewal Movements are Changing the Church, tell us something about the thesis of the book and what it is about:

ODEN: God is at work in the Church today and in surprising ways many of us have watched Mainline Christianity absorb the secularization process so completely that we have become almost demoralized about whether it can be renewed. But I think God is at work in the Church to show us that there is a lot of life left in the laity that sings the hymns of the Church, the prayers of the Church, and in our confessional tradition, and we always have the testimony of the Holy Scripture to rely on for the truth, and that is being recovered in the Mainline today. When we say the Mainline, of course what we are talking about is the group of churches that have liberalized during the twentieth century, and in an increasingly and accelerating way. Since about 1960 each decade they have more and more absorbed a kind of liberal secularization in culture, but in this book I’m trying to describe and archive and account for the texts that have borne the witness of the Renewing and Confessing movements. There are about twenty-five of them in the United Methodist tradition, there are at least that many in the Presbyterian, PCUSA, the Presbyterian Church of the United States of America. There is at least a dozen in the Episcopal Church. Now, these varied renewing and confessing movements, I’m trying to describe them, how they relate to each other, and what they mean ecumenically.

IRD: What’s been the response?

ODEN: It’s a little bit early to assess response for the simple reason that reviews do not come quickly. I’ve had favorable reviews thus far, but this book is just out so we don’t really have much of a record yet of formal response. However, informally, I know that a lot of people are reading it, and I can tell just by the quality and tenor of the response that it is meeting their needs and that it is hitting its mark in certain ways. And I’m gratified by that.

IRD: Do you have any examples?

ODEN: Yes, take for example the growing interest in Church property issues. Now this is not where we’re focused on in the Institute on Religion and Democracy, but it is an issue that’s out there in virtually every local church. Almost every locality is going to go through some kind of a discussion about who has legitimate right to the church property. Do the bureaucracies that have a claim upon the discipline and the rules of the church, they think of themselves as monitors of it, do they have a right to enter into a local church situation and control authority? Now I’m just saying that this is an issue that is, I’ve got three chapters on this issue, and there’s a lot of material in there, I believe, that people are finding thoughtful historically. That is, each one of these denominations, United Church of Canada Episcopal Church, Angelical Lutheran Church of America, United Methodist Church, and so forth. All of these churches have a confessional history, which is based upon the Apostolic testimony, upon the Scriptures. And they have a polity and a disciplinary process that has grown out of that and reinforced over literally centuries. Now whether the contemporary Church can abandon, simply abandon that language, that tradition, that ethos, is a serious question for how local church properties are going to be used and what the legitimization is for bureaucracies to run contrary to the commitments of the standards of doctrine and the standards of polity of the denomination and get off scot free and they have nobody question them. This is an issue that takes its own form in each of these denominations, and they’re very analogous in other words, what’s happening, the struggle of Lutherans, ELCA Lutherans, is almost identical to the struggle of the United Church of Christ in America and the United Church of Canada.

IRD: Yeah, and it’s even more complicated by state law.

ODEN: Yeah, exactly.

IRD: You talk in the book about the new ecumenism. Can you say a few things about that?

ODEN: Classical Christian ecumenism has emerged out of the Apostolic Witness, trying to define where the boundaries are for classical Christian doctrine, for classical Christian teaching. Now, that decision making process occurred by consensus, according to Scripture. In other words, it was all a debate about exegesis, every council that met, the conciliar process, ecumenical conciliar process, layer after layer, century after century, was a discussion about Scripture, and about what it meant. For example, when the Church ecumenically decided that it is simply not New Testament teaching to say that Jesus is not quite God, or almost God, or in Aryan way, I mean that in terms of the Aryan controversy of the fourth century, that became a definitive statement that subsequently the entire ecumenical tradition has honored and been accountable to. What happened in the twentieth century is, I call it, the old ecumenism because it is wearing out, it is losing its identity, it is becoming the fuse in its understanding of itself, its doctrinal integrity is being washed away. But the ecumenism that we’ve become accustomed to in the twentieth century is simply a dying ecumenism. We know that, for example, the instruments of that ecumenism, that is World Council of Churches and National Council of Churches, are unable, really to support themselves as institutions by support from the churches. It’s a little bit like the United Nations. The United Nations cannot get its funding from its members; it simply doesn’t collect its pledges from its members, so it is with the National Council of Churches and World Council of Churches. So where do they get their funding? They’ve got to go to the big international corporations that they’ve been complaining about for thirty years as having all of these demonic characteristics, and now they’re on their dove, especially if they have a liberal agenda politically. Now, back to the question of the New Ecumenism, the New Ecumenism is grounded in the truth of the Ancient ecumenical movement. It makes its appeal to that form of consensus formation based on Scripture that we find very clearly and repeatedly illustrated in the early Christian centuries so that crisis after crisis the church went through, it solved problems consensually. But consensual always is a reference to Scripture. The modern ecumenical movement, which I believe is an old, and a dying movement, had vitality for about fifty years. It was born in 1948, I believe it pretty much expired by the time it had its World Assembly in Zimbabwe, which was in 1998. That’s fifty years. Now, it still is continuing, but what is happening with the New Ecumenism, I guess is your question, what is the New Ecumenism? It is the discovery that is occurring profoundly between Catholics and Protestants, between Orthodox and Catholics, between Orthodox Catholics and Protestants, between Pentecostals, that we are accountable to the same Scripture, the same Lord, we have the same history of exegesis of that Scripture that instructs us even today, and it is the truth that is told by the Gospel. The truth of the New Testament testimony that is an expression of Old Testament promises. Promises of Israel are fulfilled in Jesus Christ. So interpreting that in each new historical situation is what ecumenism is all about. But when it forgets its Scriptural center and identity, which it arguably has, and it becomes essentially the pursuit of a certain kind of political idealism. Especially utopian, especially focused on statist answers to political problems, which I regard as extremely dated. In other words, the statism and the pacifism that is characterized in a great deal of, let’s say typical modern ecumenical literature. And by modern, keep in mind I mean that old ecumenical movement that’s dying. That ecumenical movement is being replaced by something much more vital, and I believe this is a work of the Holy Spirit. I think the Holy Spirit is creating a new ecumenical reality, as an ecumenical reality that is grounded in personal faith in Jesus Christ. It can take Pentecostal form, it can take Catholic form, it can take Orthodox form, it can take charismatic form, it takes many different forms. But it is a much more diffused ecumenical reality, but it’s clearly Christological, which is a problem for the modern ecumenical movement because the modern ecumenical movement has decided that it cannot affirm as one voice the Lordship, the sole Lordship of Jesus Christ, can’t do that because it wants to expand its arena so that it’s inclusive of the interreligious dialogue. So what used to be called Christian humanism is now just interreligious dialogue, or at least it is largely moving in that direction, the tendency is in that direction. So you have a tendency of amnesia, doctrinal, dogmatic amnesia in the ecumenical ethos that we have understood from the twentieth century. Twenty-first century is an entirely different matter, there is a new ecumenical reality occurring.

IRD: I wanted to ask the basic question: is it possible to turn around the Mainline, as your book title implies? Many people get very discouraged, they see membership loss of one to two percent per year that’s gone on for forty years now in almost all of these denominations. They see the average age of current members being well into their fifties, even upper fifties, well past the age of child bearing, and they begin to despair, they begin to think it’s a downward spiral, it’s just inescapable. Do you think that it’s possible to turn this around, and how could we see a turning point?

ODEN: For us humans, it is not possible. For God, it’s a synch, it’s easy. This is what the Holy Spirit does. The Holy Spirit makes possible what we conceive to be impossible. All of the sociological evidences seem to be counter to a turnaround of the Mainline, I’ll admit that. What then, is happening? First, you have a very deliberate, intentional, ecumenizing of renewal movements. This can be documented. In fact, this is what I’m trying to do in this book, in this archival in a sense, it is trying to provide documentary evidence for a consensus of persons who share classical Christian teaching in the modern world with vitality and a capacity to appeal to young people, and a sense of history, and a sense of the future. It’s God’s future and it seems to me that renewing and professing Christians today by and large are not in a despairing mood. Now, some of us who have worked and slaved and hassled Church renewal problems for decades, we’re tired. We would like to see a different vote occur at the next General Assembly. I mean, we are very weary. The Holy Spirit is not weary. I think that what is happening is deeply personal in terms of the relationship of persons to Jesus Christ. That’s what is transforming the Church, and it’s also against all the odds, transforming the United Church of Christ in America. I mean, there are congregations that are becoming accountable to the word of God in Scripture. The same is true in the United Church of Canada. Think of the enormous vitality that is emerging out of the United Church of Canada partly because of its demoralization. Put it this way, I think the Spirit is simply destroying some institutions, forget about it. We’re not going to try to revive those institution as such, that’s not our goal. Rather, our goal is to see the oneness of the body of Christ that is grounded in the truth. The only basis of ecumenical promise is the truth of Jesus Christ. God the Father made known through the history of the Son, His incarnation, His teaching, His life, death, resurrection, ascension, and coming again, and that all empowered by the work of the Spirit, of this standard triune theology. I mean, you can find it not only from the Scripture, but you can find it again and again referred in the second century, third century, fourth century. So when I use the world ecumenism, I really am talking about authentic, ancient ecumenism upon which post-modern ecumenism is emerging. It is post-modern in the sense that it is already taken seriously the death of modernity, and I think as long as we are fixated on trying to revive that Church that existed in accommodation to modern consciousness, we probably are going to feel that despair that you can so easily tap into. But that’s not where the Spirit is leading us, I don’t think.

IRD: You spoke of the confessing movements in different denominations, could you say that more? What are these movements like, what’s new about them? If someone wanted to become part of a confessing movement, how does that happen?

ODEN: You go to a church that confesses Jesus Christ as Lord and Savior. If you were a late person, you participate in everything that I am going to say is going to be absolutely familiar to you. You are going to be participating in a community that is reading Scripture, that is vitally praying for the love of God in the world, you are going to be worshipping in a community, you are going to be in a ethos in which there is an ethic of service that arises out of your understanding of God’s ministry to humanity. So I think you have to put yourself in a context in which it is possible for the Spirit to work. Let me give you a kind of radical illustration of this. If I were going to understand Islam and Islamic reality, I would put myself in an Islamic community. I would go and learn the Qur’an, I would learn what it means to pray within that community, I would be a participating and engaged person within that community of faith. Now that is actually happening within Christianity. It is actually happening within the Angelical Lutheran Church of America. It’s happening within what we call the Episcopal Church of the USA, which is in such inner conflict and strife right now. Profoundly happening, there are signs of renewal and the emergence of confessing communities in every one of these denominations, and that is really what this argument, or this, it’s really in part it’s a historical narrative, of how this has emerged. It’s taken twenty, thirty, forty years to emerge, and it has only emerged with any public visibility in the last, I would say ten or twenty years. In other words, renewing and confessing movements do not have a record of popularity where we can say, well, we come out with a series of victories, legislative victories, although we indeed are having some of those. We are actually having some of those, and it’s very unsettling to the established liberal bureaucracy and the elitism of that ethos for us to, you know, win some of these victories, we are in fact doing that. But I don’t really want to give the impression that the renewal of the Church and the confession of Jesus Christ is dependent upon the vote of a particular legislative assembly. That’s not to say that the vote of that legislative assembly is unimportant, I believe it to be extremely important, but not it’s penultimately important, and I think to hold our churches accountable, as I believe we are doing in our ministry of advocacy, we are just saying to our lay people and our clergy and our leadership and our church we are here to stay, we are not going to be schismatic of if you frighten us enough, we are going to leave. That’s a part of the heart of the turnaround. It is not intimidated, it is confident of the truth that is proclaims, and I think that that is what most unsettling for those who have a real deep, deep relativism at the heart of their ethics. They just can’t quite imagine anybody having confidence in the truth. If it’s God’s truth, that’s even worse.

IRD: Protestants have often been accused of lacking historical perspective, and I think you’re someone who has an unusual amount of historical perspective, both from your studies of the ancient Church as well as the course of your career. You started out your training, your early academic career more or less at the high tide of liberalism in the Mainline denominations, the point in which it seemed to be triumphant. I wonder if you can give us some sense of historical perspective of how things have changed in that period and maybe some reasons why you see hope in the changes that you’ve witnessed over these decades.

ODEN: Pentecostals are reading the history of the Holy Spirit in a way that they haven’t done before. The history of Pentecostalism has been a history of me and the Holy Spirit right now. But now, they are discovering that there is a history of the Holy Spirit. Lutherans are discovering that it’s not just the doctrine of justification by grace through faith that Luther taught, but that Luther taught the doctrine that Paul taught Augustine and Basal and Athanasius and Christenson and the great classical Christian tradition. So Lutherans are discovering that the truth that they are committed to, truly and rightly committed to, is a truth that’s Catholics and Orthodox and Methodists and Salvation Army people can all affirm. So there is a growing historical awareness of the, I would call it the unity of the ecumenical tradition. We’ve had so much emphasis in historical studies on diversity, I don’t mean sociological diversity, I mean how the Church has been conflicted. So Church history then becomes a history on how this movement merges, another movement emerges conflicting with it, and in the midst of all of this conflict, you don’t get a sense of the unity of the work of the Spirit in history. That is being recognized, and I believe that is a work of the Spirit, that it is being recognized.

IRD: But for the Christian in the pew, there is very little sense of history. Do you think so?

ODEN: I think yes and no. In the sense of reading history, you’re right, but in the sense of sharing honestly and deeply in the hymns of the Church, the liturgy of the Church, the prayers of the Church, the great preaching of the historic Church, I think that laymen are just eager for their clergy to lead them in this direction, and of course the clergy, being instructed by contemporary seminary education, of which I have been a part for my entire life, is not prepared to do that, not very well prepared. What the seminary wants to teach is politics, power, and relevance, egalitarianism, I mean I’m exaggerating here, but there’s a very, very strong concern that is anti-historical, that is presumptively prejudiced against a historical study, and wants to dismiss it on the grounds of it’s being inconsistent with the modern worldview. Take Bultmann for example. If Bultmann, essentially, and Tillich, who these are people that I at one time was very deeply indebted to in my younger history as a theologian, but both of them were saying that the great task of the Church is to listen to the world and accommodate to the assumptions of modern worldview. That’s what I learned in theological school. I had to unlearn it, it took me a long time.

IRD: Following up on that point, almost fifty years ago you began your theological career on the theological left, I guess you would say, and then you came to Orthodoxy later over the next twenty years. How would you summarize that journey and how would you relate it to turning around the Mainline?

Oden: Well I at least can tell my own story as an example of a life that is turned around. I grew up in a pious family in the United Methodist Church, very liberalized but pious, and I had the best education that I could have gotten at that time in theology. But I was never adequately instructed in the revelation of God in history as a tested by Scripture, as manifested concretely in Jesus Christ and is empowered by the Holy Spirit. I’m just using categories that I should have known how to use, to communicate, fifty years ago. Well, I wasn’t prepared. Now, I’ve tried to tell that story in my book called, The Rebirth of Orthodoxy. I’ve got a chapter there that really recounts how my own personal turnaround is just one tiny, tiny little example of thousands of biographies that the Holy Spirit has turned around, and I see this as having institutional effect. Now maybe not what we want yet. It is not what we want yet, we’re not going to get that institutional turnaround that we pray for, you know, at the next General Assembly of the PCUSA, or at the next General Conference of the United Methodist Church, or the United Church of Canada. It is not going to happen legislatively, but it is indeed happening, I believe, in a subtle, incremental sense. And incremental, that’s just the way the Spirit works often. The Spirit sometimes turns things around rapidly, but I think that the way in which the Spirit has worked in my life has been very, very slow. I mean, I’ve been slow, I could have been swifter if I had been more attentive.

TONKOWICH: We talk about this here in Washington with regard to legislation, that legislation is downstream from culture. That the culture needs to change and then Congress gets around to passing a law, essentially rubber-stamping what is already going on. Is that the sort of…

ODEN: I don’t want to put it quite that way, Jim, because it seems to me putting it that way says it is our task to change culture. And I think that the better way to put it is that God is at work in culture, profoundly to do what God wills to do. Despite our resistances, despite our sin, despite our guilt, and I think there are many evidences that that is occurring, and this is in a sense an evidentiary presentation. I’m presenting evidence that God’s spirit is enabling Jesus Christ to be truly confessed in the modern world, and precisely within the institutions, the deteriorating institutions of the Mainline. In such a way that those institutions are being affected, maybe not fundamentally yet, but they are in the process of being affected. And when I say turnaround, it’s not like a quick turnaround, I mean the metaphor on the cover of the book is a very slow process. I mean you’ve got a little bitty tug boat there with a ship that may weigh who knows how many thousands of tons, but it’s a process of movement that is actually occurring. And I think the measure of that movement is the anxiety of the liberal elites. They know we are here, and they are very disturbed about what we are doing, and I would put it a little differently. I think what they are disturbed about is what God is doing, and all we are doing is just pointing now and then to what God is doing in the world and in the Church.

IRD: Why do you think it’s important to turn around the Mainline? Is there something particular in that heritage that is valuable to the universal Church to have that revived?

ODEN: Right. What State did you grow up in?

TONKOWICH: Maryland

ODEN: Maryland, okay. Now, in your hometown, there are churches there with histories, and those churches arguably have been, many of them, or some of them, have been, what’s the proper word here, is it taken over? Something like that, by an ideology that is alien to ancient ecumenical Christian teaching. And that ideology has become prevalent in the bureaucracy that pretends to speak for all of us. Now what are the reasons the Institute on Religion and Democracy exists is to make it clear, as far as we are able, that there are voices, determined and committed voices, within these churches that are saying we have an entirely different understanding of justice, of the historical process, of God’s mercy and love, and we see you representing through the media to the political order. So, one of the reasons we’re here in Washington is that we want that witness to be modified and critiqued. We are critical, and we hope that we can continue to be critical with charity, and with a sense of mercy, and due process, and political fairness. But we will be heard, we are being heard. And we’re determined to keep on doing it. It’s not determination and that confidence, we have it. And I think we are facing people in a defensive bureaucracy that definitely don’t have it, and they’re mystified by us. They just don’t get it, and are expecting any intelligent person to accommodate to the assumptions of the modernity. That’s, I mean, that would be the intelligent thing to do, but that’s not what we’re doing. We are accountable to the word of God in Scripture, as it has been interpreted by history of interpretation of Scripture.

IRD: Now, given the evidence that you’ve worked on and put together, what would you say to the person who’s in a Presbyterian church, or an Episcopal church, and looking at what’s going on in the denomination, perhaps even within their own parish, and saying what in the world am I doing here? How would you respond to that person?

ODEN: That person can always pray, stand before God, confessing an intercession for the Church and for the society. So there’s no barrier to intercession. That person can also become incrementally grounded in the classical Christian tradition and its teaching. That person can stand as a beacon of a testimony, wherever that person happens to be, in whatever church to the truth that God has been made known in Jesus Christ. There’s no inhibition to that. If you are a pastor in a liberal church, one of the great things about the liberal tradition is that you have freedom of the pulpit. So far, pastors in liberal churches to say to me, “I’m afraid to preach scriptural convictions,” they’re not very scriptural and not very convicted if that’s the case. I want to encourage that person, and there are many of them, many of them, to not peremptorily think that an act of separation from a corrupt organization is necessarily a morally justifiable act. Simply separating yourself from an organization that you can see has wheat and tears in it, calls for you to go back to the teaching of Jesus and learn from Him that as long as we have this body of Christ, the people of God, we will have wheat and tears. That is, we will have weeds, we got weeds in the Church, we got a lot of them. We got so many of them that it almost seems like there’s nothing but weeds. But, our task is to work patiently and incrementally in the vineyard, in whatever vineyard we are. This is a clear mandate for both Luther and Calvin that you are called to serve where you are, not to necessarily pretend to create a new situation in which to serve, but, “Do what is at hand,” as Luther says.

Comment by MikeS on May 20, 2017 at 1:39 pm

Yes, there are always wheat and tares. But what are people supposed to do when (from the point of view of traditional Christianity) the denomination becomes institutionally committed to being tares?

Comment by Paul R Buckhiester on June 3, 2017 at 8:28 pm

Aryan or Arian?