Politicians are after the next election, “but Anglicans should be after the next generation,” exhorted Archbishop Stephen Kaziimba of the Anglican Church in Uganda. “God is calling us to an active faith.”

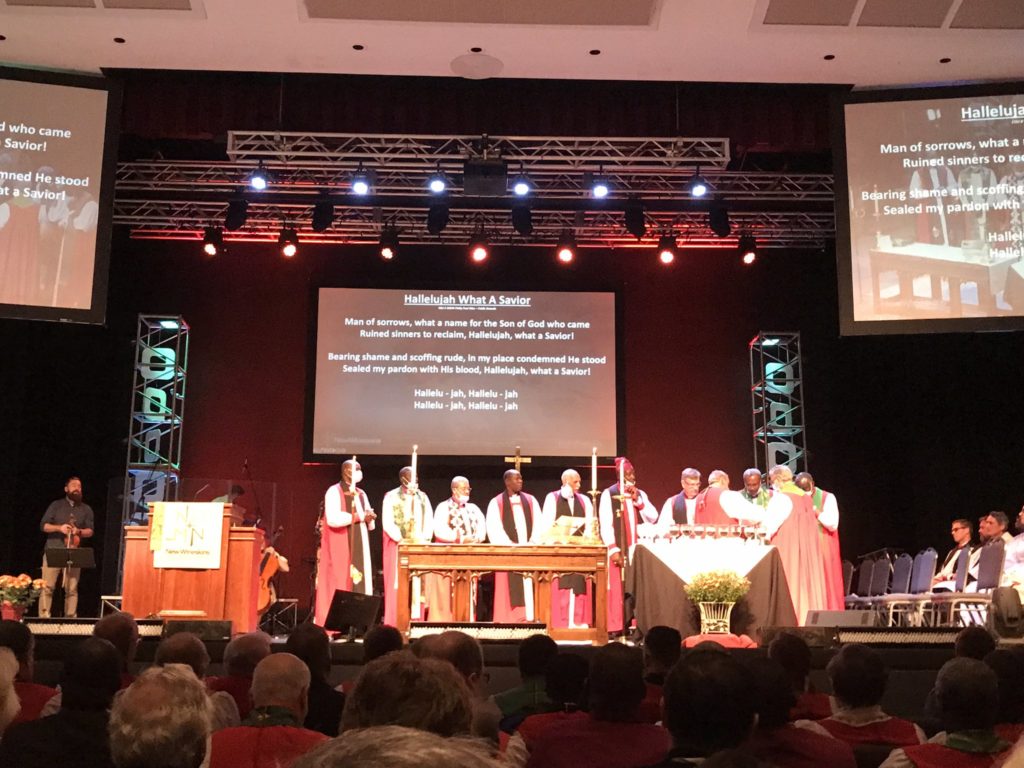

Kaziimba spoke at New Wineskins for Global Mission, a triennial gathering of mission agencies, relief and development groups, seminaries, clergy and laity. The conference drew more than 2,000 registrants (an increase from 1,200 in 2019) to the mountains of western North Carolina September 22-25. A parallel youth event drew 218 children and young adults.

Begun in 1994 as a gathering of the Episcopal Church Missionary Community, New Wineskins has grown across 10 conferences to become a vibrant pan-Anglican event that includes participants from many Anglican provinces and other Christian traditions. I spoke with Presbyterians and Lutherans, among others.

Themed “One Mission”, the conference centered upon the Great Commission and the scripture Malachi 1:11: “My name will be great among the nations from where the sun rises to where it sets.”

Meeting a Need

Kaziimba preached at a concluding service of Holy Communion, but his message – that Christians receive an individual calling from God to missionary work both here and abroad and should accept this as an act of obedience – pervaded the conference.

Those called to Christian missionary work need not have their “ducks in a row”, several speakers insisted.

“It’s through our need that we earn the right to enter into that struggle with others,” conference speaker Gwen Adams shared in a plenary session presentation.

Adams, author of Crazy Church Ladies, shared in a conference plenary session about her work as Executive Director of Priceless, an Alaska-based anti-trafficking organization. Priceless was begun out of a women’s group from a local church faced with a growing awareness that sex trafficking was not just a third-world problem, but that it was thriving in Alaska.

Jesus, Adams noted, models need in Biblical accounts of dining at people’s homes, asking the Samaritan woman for water at the well, and in sending his disciples to obtain the donkey upon which he enters Jerusalem.

“He shows up with needs and allows those to whom he is ministering to meet that need,” Adams explained. “It removes a power imbalance, tears down barriers to friendship, and builds a foundation for trust to form.”

For Adams, this meant admitting the limits of her own knowledge and experience, asking a previous victim of trafficking – one who was expressly not interested in Christianity – to educate her.

“You’re right, I know nothing,” Adams admitted to the woman about her lack of qualifications to lead an anti-trafficking effort. “Would you teach me what I do not know?”

A deeper relationship formed, and knowledge from the woman helped shape not only Adams’ organization, but also Alaska’s anti-trafficking policies and the training of law enforcement.

An Inefficient Love

Interspersed with teaching, missionaries offered testimonies from their mission fields of Turkey, Sudan, Uganda and Honduras, among others.

“Love doesn’t conform to the world’s standards of efficiency,” shared “Jacob Knox” (a pseudonym) in sharing his family’s missionary work in a majority-Muslim context, recounting a woman who faced shame from a divorce and came to belief in Christ and was baptized. “This makes perfect sense when we think about how the heart of God works.”

Knox spoke of gradual, sustained effort to build relationships, with unexpected opportunities arising in a way that could only be credited to God’s providence. Among these was an invitation to speak privately with Islamic scholars at a leading university about the Gospel.

Knox was among many at the conference who minister in countries where Christian mission work is either discouraged or outright prohibited, and where new believers can see negative familial or legal consequences for a decision to follow Jesus Christ.

A significant number of mission workers at the New Wineskins conference wore red lanyards, indicating that they should not be photographed due to the sensitivity of their mission field.

Disciple Making Disagreement

The conference was not without disagreement. A presentation by Contagious Disciple Making author David Watson during the conference’s opening night promoted a Disciple Making Movements (DMM) strategy. Known as the Discovery Bible Study (DBS) Method, Watson’s strategy calls for world-wide rapid church multiplication.

Several groups with a longstanding participation in New Wineskins expressed concern at Watson’s claims and doctrinal positions, among them officials with Anglican Frontier Missions (I serve on the board of AFM) and Trinity School for Ministry, an evangelical seminary in the Anglican tradition.

Watson’s methodology is of great interest, and I positively received his emphasis on scripture study. That being said, the claimed vast number of new converts and churches planted through his DBS method could not be verified (Watson insists these numbers are audited). Puzzlingly, Watson claims his mission strategy, among other things, has led an entire Islamic-majority nation to Christ. No one at the conference whom I spoke with was aware of what this unnamed nation could be.

Lay leaders from my own Anglican parish attest to the usefulness of DBS while cautioning against a preoccupation with numbers. Watson presented significant doctrinal positions that affect how mission work is done, including a suspicion of theological training. I would argue that learning theology is not an impediment to serving God.

‘Drinking from the Firehose’

New Wineskins is unique in whom it brings together: energetic workers from varied backgrounds across the Anglican tradition, united in their eagerness to share the Gospel in a world desperately in need of it. Nearly two dozen pre-conferences were hosted by various Anglican ministry groups.

It is, as New Wineskins Executive Director Jenny Noyes characterized, like “drinking from the firehose” for three solid days of programming that moves at a brisk pace. “I hope that your hearts have been broken that you have met Jesus in this place, and that you have received healing.”

The presence of the Holy Spirit was felt by participants whom I spoke with, many of whom were ministering in challenging contexts and in need of the fellowship and refreshment made possible by the conference. To my knowledge, New Wineskins is the only recurring gathering that continues to bring together members of the Anglican Church in North America and orthodox members of the Episcopal Church, and it is inclusive of different forms of Anglican churchmanship.

“Be faithful in the task you have now,” shared “Luke and Abby Michaels” (pseudonyms), cross-cultural workers in North Africa with Anglican Frontier Missions who quoted from Galatians 6:9. “Persevere, and do not grow weary of doing good.”

Read More:

IRD’s coverage of the 2019 New Wineskins conference is viewable here. 2016 is here and 2013 is here.

Comment by MJ on October 1, 2022 at 7:48 pm

The Episcopal Church Missionary Community was actually started in 1974 by the Rev. Walter Hannum and his wife Louise in Pasadena, California. They were a gracious and hospitable presence for Episcopal and Anglican students at Fuller Seminary for many years.

Comment by Jeffrey Walton on October 3, 2022 at 10:30 am

That’s good to note, Mark. I’ve adjusted the text to read that it was begun in 1994 as a conference of the Episcopal Church Missionary Community, since the organization itself (also known as New Wineskins) is older than the conference. My understanding is that the name of the organization was changed in 2006 to mirror the existing conference name.