Recently deceased Civil Rights leader John Lewis wrote in 1998 for The New York Times about forgiving his old segregationist nemesis George Wallace:

Although we had long been adversaries, I did not meet Governor Wallace until 1979. During that meeting, I could tell that he was a changed man; he was engaged in a campaign to seek forgiveness from the same African-Americans he had oppressed. He acknowledged his bigotry and assumed responsibility for the harm he had caused. He wanted to be forgiven.

And:

When I met George Wallace, I had to forgive him, because to do otherwise — to hate him — would only perpetuate the evil system we sought to destroy. George Wallace should be remembered for his capacity to change. And we are better as a nation because of our capacity to forgive and to acknowledge that our political leaders are human and largely a reflection of the social currents in the river of history.

Lewis concluded:

I can never forget what George Wallace said and did as Governor, as a national leader and as a political opportunist. But our ability to forgive serves a higher moral purpose in our society. Through genuine repentance and forgiveness, the soul of our nation is redeemed. George Wallace deserves to be remembered for his effort to redeem his soul and in so doing to mend the fabric of American society.

Wallace was the Alabama governor who infamously proclaimed “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, and segregation forever!” He had begun in politics as a relative racial progressive but shifted to racial demagoguery to win elections. A lifelong active Methodist and church leader, he did not allow Christianity to inhibit his ambition. His wife’s death by cancer started an inner transformation.

But more decisively, Wallace’s paralysis from a 1972 assassination attempt, followed by years of physical torment, brought him spiritual reflection and empathy. His daughter recounts that while in the hospital he was visited by Shirley Chisholm, the first black woman member of U.S. Congress, which profoundly affected him.

In 1979 Wallace visited the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, where Martin Luther King Jr had pastored, and offered his apologies. As his daughter recounted, he told the congregation: “I’ve learned what suffering means in a way that was impossible. I think I can understand something of the pain that black people have come to endure. I know I contributed to that pain and I can only ask for your forgiveness.”

Wallace also began phoning old adversaries, especially black people, whom he had wronged during his political career. As his son recounted, “His own suffering and purification that brings and the enlightenment that brings, and his realization that some things he had done and said could have caused others to suffer, bothered him, concerned him as a Christian.”

Lewis, who was beaten by Wallace’s Alabama state troopers in 1965, got a call from Wallace and later recalled:

He was very candid, very frank, I thought. He literally poured out his soul and heart to me. Uh, it was almost like a confession, like I was his priest. He was telling me everything. That he did some things that was wrong, and that he was not proud of. He, he kept saying to me, “John, I don’t hate anybody. I, I don’t hate anybody.”

Lewis, who attended a Baptist seminary and was an ordained Baptist minister, of course understood the imperative and power of forgiveness for individuals and society. He also appreciated the mystery and majesty of Providence. He saw Wallace and other foes as part of a larger cosmic drama in which righteousness prevails through conflict and suffering:

Whether at the bridge in Selma, at a bombed church in Birmingham or on the schoolhouse steps, George Wallace and I were thrust together by fate, by our personal conviction and principle and by what I like to call the spirit of history. The civil rights movement achieved its goals in the person of Mr. Wallace, because he grew to see that we as human beings are joined by a common bond.

As a leader in the largely clergy-led Civil Rights Movement of 1960s, Lewis like MLK understood that persuasion and forgiveness better achieve lasting justice than do violence and vengeance. Wallace and the nation were convicted by appeals to conscience. MLK and his colleagues, who read Reinhold Niebuhr, were Christian Realists of a kind. They sought justice but knew demands for complete justice were unachievable and destructive. Approximate justice, sought by sinners against sinners, must be ameliorated by mercy.

On this topic Jordan Ballor recently cited Jewish political theorist Hannah Arendt: “The freedom contained in Jesus’ teachings of forgiveness is the freedom from vengeance, which encloses both doer and sufferer in the relentless automatism of the action process, which by itself need never come to an end.”

Absent forgiveness, there’s no peace among persons or within societies. This message, exemplified by Lewis extending mercy to Wallace, is much needed today, when zealous activisms dogmatically demand justice without mercy. All advocacies across the spectrum must recall their own limitations before waging their political wars. Reinhold Niebuhr warned:

The peace of a democratic community therefore depends upon some ultimate realization that our conception of justice is not quite as final as we imagine. It is made from our perspective and colored by our interest. If we do not realize this fact we become more & more fanatic in pressing for our solution of the problem, in asserting it is the only possible solution and in regarding our opponent, not merely as our opponent, but as an opponent of the common good.

There can be no common good without societal forgiveness and mercy, which Lewis knew well.

Comment by Rev. Dr. Lee D Cary (ret. UM clergy) on August 3, 2020 at 8:15 am

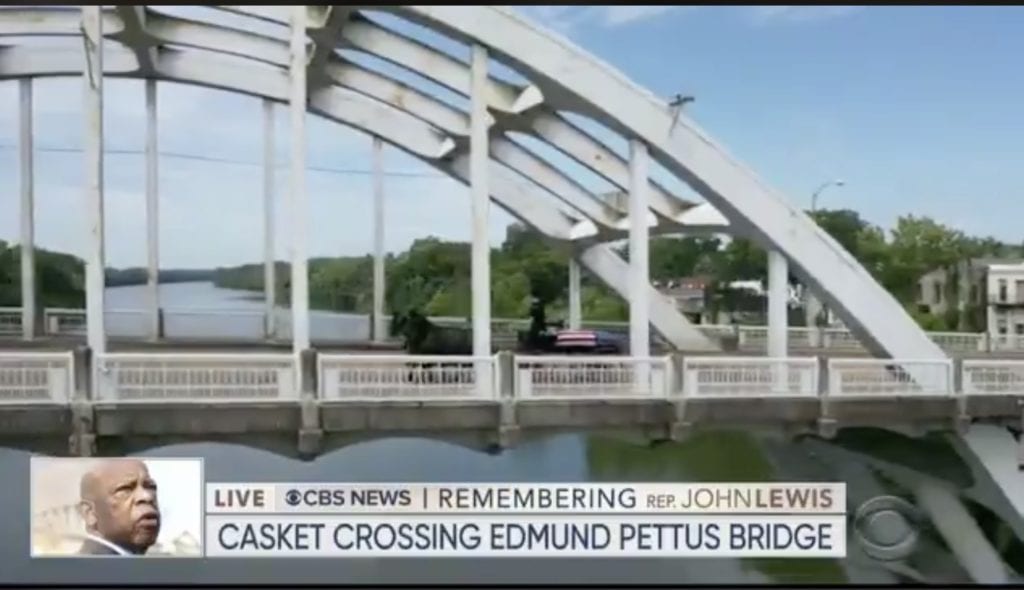

The sad thing about John Lewis’ life is that he never made it alive across the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

The old MLK-led Civil Rights Movement moved on long before Lewis did, but he continued living in it.

So, when a “new civil rights movement” emerged in Black Lives Matter he assumed it was just an extension of the old, and along with his political party, he fully aligned himself with it.

Hannah Arendt, quoted above, in her book “The Origins of Totalitarianism,” wrote:

“The force possessed by totalitarian propaganda…lies in its ability to shut the masses off from the real world. The only signs which the real world still offers to the understanding of the unintegrated and disintegrating masses – whom every new stroke of ill luck makes more gullible – are, so to speak, its lacunae, the questions it does not care to discuss publicly, or the rumors it does not dare to contradict because they hit, although in an exaggerated and deformed way, some sore spot.” (p. 353)

Lewis kneeled to a cancel culture movement that does not stand for what he once boldly marched.

Comment by Jim on August 3, 2020 at 9:18 am

Very well put Lee. Lewis could have offered the same climate of forgiveness that George Wallace exhibited. Instead, he opted for the storyline of victim hood through out his life.

Comment by Donald on August 9, 2020 at 7:42 am

The virtue signalling of various denominational leaders, captains of industry and of course the political opportunists of our present age manage to combine extreme self-righteousness along with their crocodile tears of guilt-laden confessions. They are nauseating to watch, hear or read. The sermon on Wealth Redistribution noted on this page is only the most recent example of such posturing. Thanks for reminding us about the imperative to forgive those who have wronged us…and to seek it from those we have wronged.