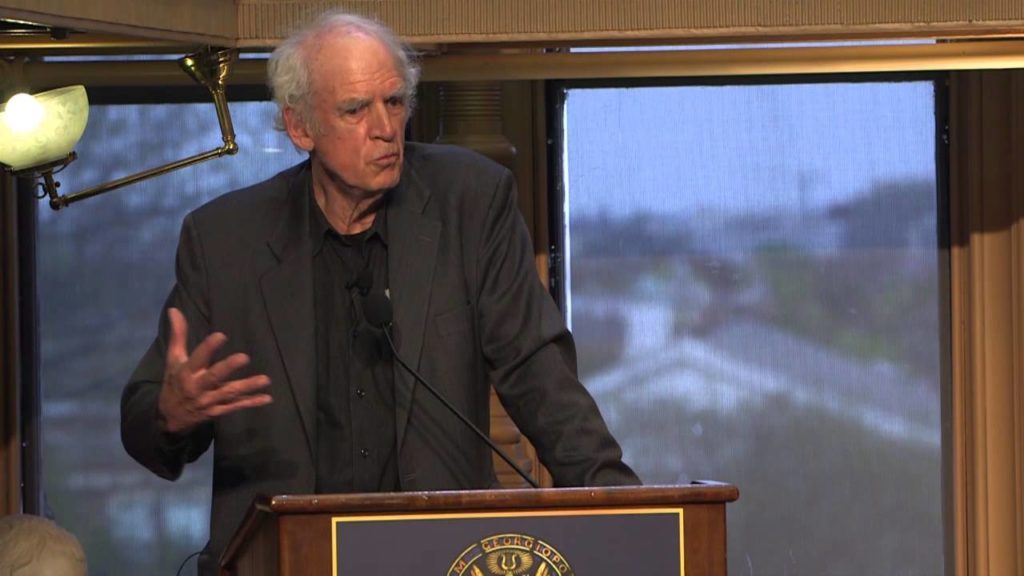

Renowned philosopher Charles Taylor argued that openness and solidarity will save pluralism from the corrosive powers of populism. The author of the widely influential book, A Secular Age, stated his beliefs to a virtual audience hosted by the Berkley Center for Religion, Peace and World Affairs at Georgetown University on June 11, 2020. Drawing from his book, Taylor used his philosophical views to advocate against nationalism and traditional religion in exchange for pluralism.

Taylor lays the groundwork of his philosophical argument by first explaining that, in the Middle Ages, essentially everyone accepted the fact that they lived within a morally ordered cosmos. Today, however, societies share the natural science view where man-made contexts make and shape an individual’s reality. Because everyone shares this understanding, Taylor refers to it as the immanent frame.

Because the secular imminent frame does not judge a faith as more valid than any other, it does not prevent the possibility of true faith, according to Taylor. Catholic modernity, for example, is about “practicing Catholicism in a way that makes sense within contemporary society.” Taylor concludes that the secular age is therefore one packed with opportunities for making better religious narratives, ultimately leading to pluralism—secularism’s crowning jewel.

However, societies respond to the secular immanent frame differently, and populism—not pluralism—is sometimes the result. People who feel neglected by elites are specifically prone to the populist mindset, and Taylor uses the United States and President Trump as a contemporary example of this sentiment.

But on the other end of the western world, the communist regime suppressed Catholicism in Poland for so long that, upon liberation, many people felt that Poland’s lost identity must be reasserted through an ethnoreligious homogeneity. Tayler argues that Poland’s populist reaction consequently affirmed the rule of the majority without a concern for minority rights. Likewise, the cultural evolution of Pakistan shows a dramatic reaction against secularism, holding one of the narrowest notions of Sharia law and trying citizens for blasphemy on death row. If the secular immanent frame and its product of pluralism causes negative experiences, Taylor concludes, societies will crave an ethnoreligious homogeneity.

Taylor then offers two ways to prevent populism, the first of which is openness. Because the examples Taylor gives show how “populism is fueled by a tremendous fear of losing the national identity,” this fear must be mitigated. Cultivating an open attitude towards change is, according to Taylor, one of the best ways to do so. This openness necessitates letting go of “narrow” religious and political beliefs, but Taylor did not draw a line between narrow and open beliefs. So, while fear-driven populism can lead to many injustices, the price of a “healthy pluralism” might be just as high, depending on who sets it.

Taylor’s second method to prevent populism is solidarity. Using the Black Lives Matter protests as an example, Taylor argues that the wide-spread reaction to George Floyd’s death happened because of the solidarity already created through the coronavirus pandemic. This reaction, Taylor assumes, is “wonderful.” People are mobilizing for justice because they share a sense of solidarity with their marginalized neighbors—a pure and binding feeling that was not present before the pandemic.

On the international scale, this pandemic-driven solidarity could help nations cooperate and address expansive problems together, such as climate change and poverty. Solidarity, Taylor concludes, makes large-scale justice possible.

While Taylor’s prescriptions for world justice seem optimistic, he points out the simple, small-scale fact that pandemic-driven solidarity reminds people that they were made for relationship. This reminder, Taylor says, also helps “revitalize a healthy pluralism.” Even with the rise of big data and artificial intelligence, the psychological temptation to reduce human beings to mechanistic patterns becomes more difficult amidst the solidarity aroused by the pandemic.

Taylor threads this back into the problem of populism: there is not one single, stagnant national identity for any society. People are complex, changing, and need relationship more than strict, mechanistic patterns. Solidarity reminds people of this fact, inviting them to affirm pluralism over populism.

In sum, Taylor contends that the secular immanent frame creates an opportunity for vibrant pluralism. For this pluralism to be realized, however, people must be open to change. If openness fails and populism makes it impossible to cast off narrow national identities, solidarity can transform the stress of a society into a revitalized pluralism.

Comment by Ken Webb on June 30, 2020 at 6:41 pm

“The natural science view where man-made contexts make and shape an individual’s reality… ultimately leading to pluralism—secularism’s crowning jewel… packed with opportunities for making better religious narratives,” would be very attractive if not for the stubborn insistence of orthodox Christianity that reality is fixed/given, true faith has an objective object, and plurality of truth seems to be an oxymoron. Since Jesus used the definite article “the” to specify his status as “the way, the truth and the life,” it is frightening to me to consider making an attempt at a “better religious narrative.” Many of us still find the best place to stand is on the foundation of the Apostles, Prophets, and Christ Jesus the Cornerstone. That is religious narrative enough for us. I love the study of philosophy, and have often second guessed my choice to pursue an M.Div. and D.Min as opposed to philosophy degrees, but after 30 years in ministry I think I did the right thing pointing to a trustworthy Bible, the God who holds reality together, Jesus who addresses our deepest need, and trying to nurture the family of faith. At births, deaths, weddings, sick beds and grave sides there is little comfort in new narratives or truths that are mere cultural trends.

Comment by Timothy on July 1, 2020 at 2:24 am

Author Kate Cvancara deserves a medal for racking her brain to analyze the great philosopher. Reminds me of several philosophy classes I took at my private university back in the 1970’s. I walked away from secular philosophy. A strong nation needs populism and pluralism to some degree, grounded on spiritual/moral foundation. My question for Dr. Taylor is ‘where do you draw the line?’

Comment by John on July 3, 2020 at 11:38 am

The problem with his analysis is the history of secularism. It aims at displacement of religion, all religion but especially the great religions that have shaped world civilization since about the 6th century BC. It relies heavily on the scientific method, and puts aside the fact that modern science is based on presuppositions that arise out of the Jewish and Christian faith in a creator God who has ordered a a universe,, and Greek philosophy which produced an abstract view compatible with this biblical faith. The Enlightenment view rejects both the biblical view and metaphysics and displaces its with a godless view, that of scientism. Lewis Mumford called it a new worship of Apollo, the god of Reason, but is also evokes other gods, Aphrodite and Mars. Which is why the French Revolution quickly developed on a war against Christianity. That war has not ended.

Comment by Bill Lang on July 3, 2020 at 11:47 am

In going through this article I find that Taylor’s arguments to be a reiteration found in similar light through the ages. Secularism seems to be no more than the temptation, “you shall become as the gods” while usurping God. He is clearly echoing Fletcher’s Situation Ethics as the core of his philosophy.

His citing of the reaction to George Floyd loses validity when one considers that it was not solidarity but rather instigation by outsiders who sparked the many riots while being bolster by the media and the cowardliness of leaders to stand up for law and order.

The true philosopher is to be above prejudices. Nor should he be swayed by popular folk philosophy.

Comment by Peter james on September 14, 2020 at 12:38 am

It doesn’t feel like the opposite of populism is presently a healthy pluralism. Pluralism rewards those who outflank it’s current state, with little tolerance for those that don’t get in line. We all fear when the pluralist might come knocking seeking a infraction, perhaps asking “have you been drinking outside of our well?” We are all afraid to say there’s no such thing as race, though we know it’s true. Our pluralism is regulated and audited by the profiteers, leaving perhaps this version as the best the immanent frame can muster.