Article originally published at ChristianHeadlines.com and is re-posted with permission.

by Jim Tonkowich

Sitting on my bookshelf collecting dust are far too many unread books. You too, huh? This being Lent I pulled one off that–no surprise here–turns out to be a treasure: Alan Jacob’s book Original Sin: A Cultural History.

“What’s wrong with the world?” someone asked G. K. Chesterton who famously replied, “I am.” And what’s wrong with me? Original sin in the form of the guilt that is removed, according to Church tradition, by baptism and in the form of a twisted will that we battle every day, all life long. “I don’t understand my own actions,” wrote St. Paul to the Romans (7:15), “For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate.” From Original Sin flows all of our quotidian unoriginal sins.

But how, asks Jacobs, was it possible that Adam and Eve sinned? If they were perfect and innocent, how was it that they toyed with and finally committed the great act of disobedience? Was there some flaw or sin behind the eating of the forbidden fruit? Was Satan really so compelling a debater? How was the Fall even possible?

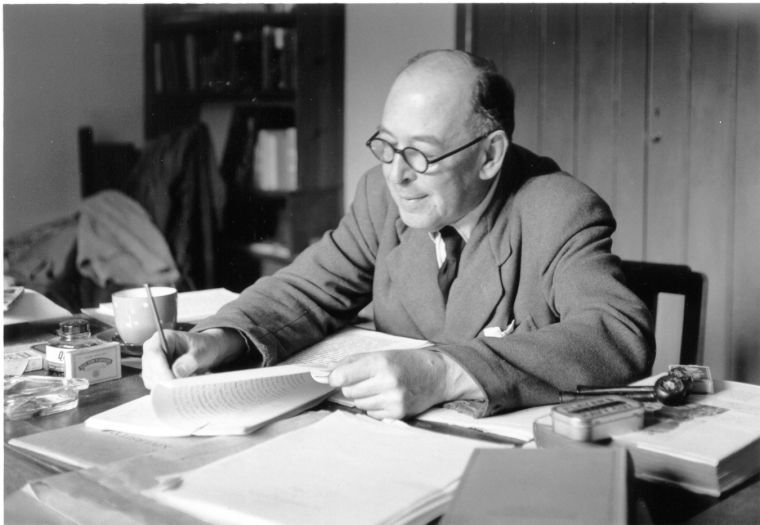

For help, Jacobs turns to C. S. Lewis. In his science fiction novel Perelandra, Lewis replays the temptation of Eve far from Eden on another new world, on Venus. On Venus, a planet of seas and floating islands, Lewis’s hero, Dr. Ransom, meets “the Lady” who is the Eve of her world. He also meets his nemesis, Dr. Weston or, more accurately, the body of Dr. Weston animated by the devil even as the devil animated the serpent in the Garden.

In tempting the Lady to disobey God, Weston begins with reason. But, Jacobs points out, “Disobedience simply makes no sense to her.” The Lady tells Weston, “To walk out of His will is to walk into nowhere.”

Then Jacobs adds, “Sensing that the condition of her mind makes further argument pointless, the tempter changes his tact, and interestingly, he begins to tell her stories.”

Jacobs goes on, “But what is especially interesting here is Lewis’s suggestion that before the rational mind can be convinced by argument, the imagination must be shaped and formed so that the person responds in a certain way–with certain feelings–to an argument. Only after he has told many, many stories does the tempter return to direct persuasion.”

While literacy seems to have fallen on hard times in our culture, the telling of stories and the hearing of stories has not. In fact, at Wheaton College, where Alan Jacobs teaches English, a group of students recently boycotted a lecture by a woman who had been a lesbian prior to her conversion to Christianity. That may be her story, the students insisted, but it is not nor should it be everybody’s story. Every story is different.

Hollywood, television, what passes as the news, popular novelists, and thousands of advocacy groups contribute story upon story. While there are voices decrying violence in our world, the stories told at the movies and in video games make us increasingly comfortable with carnage. The story of “funny, charming, winsome” Ellen DeGeneres and her relationship with Portia de Rossi hints that “Love is love,” “Love makes a family,” and “Marriage equity” and undermines logic and Natural Law reasoning about marriage. Photos of polar bears apparently clinging to the last ice flow in the Arctic color how people treat even the hard science that indicates that the Arctic won’t be melting away any time soon.

Stories, not arguments, shape imaginations and imaginations shape feelings and feelings shape the way we hear the arguments. If stories convince us that certain positions are absurd or foolish, reason, logic, and data will look foolish, mean-spirited, and absurd.

Which means that the battle today is not for better arguments (important as they are), but for better stories.

Let me quickly add that I do not mean better stories alone as though narrative preaching or the next Narnia movie or some combination of images will turn the culture on their own. They won’t. Jesus is the divine Logos, not the divine narrative. We are still obligated to give a reason for the hope that is in us (1Peter 3:15). Narrative will never supplant apologetics.

Nonetheless having said that, as C. S. Lewis knew, as G. K. Chesterton knew, as Alan Jacobs knows, and as every good preacher knows, good stories capture imaginations so that the reasons for our hope, our faith, and our way of life can be heard, heeded, and received.

A good story can change people’s hearts so let’s get writing.

Comment by cleareyedtruthmeister on March 29, 2014 at 5:27 pm

Very good article that helps explain why we are in the shape we are in today.

Except in those increasingly rare individuals who have learned to subvert emotion to reason and realism, the capacity to empathize with a character, be they villain or hero, is what drives affection, and affection is what drives the political and cultural ethos.

Thus, as Christians, we must learn to read and write the “good” stories, the kind that C. S. Lewis was masterful at contructing, in order to counter the depraved secular narratives so prevalent today.