Former Defense Secretary Robert Gates’ new memoir has gained lots of media for its critique of the Obama Administration. Based on the excerpts, he was exasperated by the administration’s sometimes crass political calculations. He found Congress to be incompetent. He hated much of his job almost from the start. At night he went home to an empty house and ate frozen dinners, as his wife remained at their home on the West Coast during his term as Defense Secretary. Apparently, and again understandably, Gates at the time was frustrated that admirals and generals often got personal chefs but their superior, the Secretary of Defense, was on his own.

Gates is a very distinguished public servant who spent much of 4 decades in government. He was CIA director when I worked there, and I shook his hand once at his departure ceremony at the end of President George H. W. Bush’s term. He did attend a United Methodist congregation in Northern Virginia where I had friends. Later, after he left the area, I was told he attended a non-denominational church.

No doubt many of Gates’ critiques are factual and justified. As a long-time veteran of Washington, Gate’s chagrin and seeming surprise over political calculations by a White House or Congress seem somewhat misplaced. Maybe the publisher pushed for such emphases. No Congress or White House has ever been any other than supremely political, as it is central to governance in a democracy. Gates’ dislike for his job is understandable but his acceptance of the office is less so, as he had to have known all the pressures, chicanery, incompetence, prevaricating and hypocrisy that any holder of high office will encounter in the administration of his or her duties. It’s also unfortunate that Mrs. Gates didn’t live with her husband in Washington, DC at a particularly grueling time when her companionship presumably would have been helpful. In the evening, by himself, Gates dutifully wrote letters to the families of fallen service members.

In general, people who hate their job shouldn’t stay in that job unless economic necessity compels it. Every high office is a special honor. Serving as Secretary of Defense, especially during two wars, is especially hair-raising. No doubt Gates returned to Washington, DC, at President George W. Bush’s request, out of a sense of duty, and remained in place after Obama’s reelection out of duty and commitment to continuity. But service without joie de vivre, even if undergird by great competence and dedication, can often be ruinous.

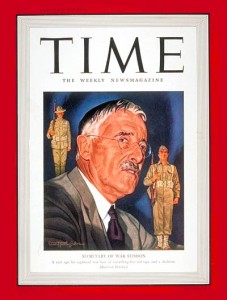

One of America’s great unsung heroes is Henry Stimson, War Secretary during all of World War II, and like Gates, a Republican serving under a Democrat, appointed to create a sense of bipartisanship in far more dire times. Already age almost 73 by the time of his appointment after a lifetime of service, he had been a friend to Theodore Roosevelt and served as Secretary of War to William Howard Taft. Later he was Secretary of State to Herbert Hoover. Under FDR he presided over America’s largest ever military force, consuming about one third of the economy. By all accounts he was super competent and worked seamlessly with the Congress and President Roosevelt, who respectfully called him only by his last name.

In the wild chaos during which America went from virtually defenseless to having the world’s most powerful armed forces, Stimson must have been frequently frustrated. Congress then as now was egotistical and prickly. FDR could be fickle and was supremely political. Stimson spearheaded the Atomic weapons program, about which FDR told his successor Harry Truman nothing, leaving Stimson with the duty to inform the new President after FDR’s death. It was largely Stimson who presided over the when and where of the weapon’s deployment, a steep responsibility. Yet Stimson mostly served without public complaint. His memoirs were highly acclaimed but not critical. Stimson was a lifelong practicing Presbyterian whose faith was deep but private.

Stimson left office at age 78 and lived another 5 years. His 5 years as War Secretary, full of crises no predecessor had ever experienced, must have drained him. Yet he seems also to have thrived in his work, and maybe it prolonged his life. Joy and gratitude in every vocation, no matter the adversity, are virtues sometimes hard to attain but always rewarding.

Comment by Daniel on January 9, 2014 at 10:22 am

Good Lutheran theology in your article title. A nice piece about how men bear up in trying times.