Several Catholic thinkers inclined towards integralism (Wikipedia definition: “Catholic faith should be the basis of public law and public policy within civil society.”) wrote interestingly in defense of European style cultural Christianity. Many American Evangelical elites disparage this concept, whose USA Protestant approximate equivalent is civil religion, as an unacceptable dilution of authentic faith.

But these Catholic thinkers explain:

The tradition of cultural Christianity recognizes—and embraces—key elements overlooked by liberalism’s transmutation of Christianity into global humanitarianism. As the French political philosopher Pierre Manent put it in describing his own country, we live in nations marked by Christianity—not to the exclusion of other religions, but stamped nonetheless by the Gospel and the Cross. Christian nations take care of the sick and the poor, preserve life from conception until natural death, incarnate their faith in holidays and festivals, and inspire public life with hope for eternity.

And:

Historic Christianity, especially Catholic Christianity, is a mass, public religion, and it has ever sought to encompass civilization. From the beginning of his public ministry, Jesus of Nazareth was drawn to the company of the masses, to weddings and funerals and other scenes expressing the ordinary joys, aspirations, and sorrows of ordinary people. We must not forget that even as the crowds turned against him when his teaching got hard, and even as they voted to crucify him, it was precisely the masses he sought, and seeks, to save.

To critics who complain that cultural Christianity is “insincere and hypocritical, tawdry and chauvinistic,” they respond:

The critics’ charges are false, their claims utterly alien to the great commission of historic Christianity. Intending to safeguard the purity of sincere faith, they in fact propose an unpardonable abdication of responsibility that owes more to an individualized, privatized and modernized account of the faith than to anything in the tradition. Cultural Christianity has dominated the Western world for the better part of two millennia, and we believe it is very much worth defending once more.

These Catholic writers are insightful in rejecting the privatization of faith often implicitly preferred by some USA Protestants, who prioritize more exclusive focus on evangelism or church purity, and who believe civic faith is intrinsically corrupt. Sadly, these Catholic writers do not cite as exemplars of cultural Christianity the prayers at USA civic events, or the Church of England’s bishops opposing assisted suicide. Instead, they cite mostly right-wing European nationalist leaders who cynically exploit symbols of Christianity, like Italy’s Matteo Salini waving a rosary at a political rally along with France’s Marion Maréchal and Hungary’s Viktor Orban. Why not include Vladimir Putin, who is a tremendous patron of Russian Orthodoxy?

More disturbingly, in light of their implied support for its contemporary application, they note St. Augustine “never wavered from the view that the expansion of Christianity with the assistance of temporal power belonged to the very providence of God.” Undoubtedly true, and in Augustine’s context arguably understandable, although USA critics of Constantinianism would vigorously disagree. Integralists argue for state advocacy today of religion, specifically Catholicism, even through coercion of persons outside that faith. Should non-Christians and non-Catholics be compelled to subsidize and live under the rule of a Catholic-themed regime? The integralist vision says yes.

These writers offer their integralist-inspired vision of cultural Christianity as the alternative to their favorite bete-noire, “liberalism,” which they equate with rabid secularism, sterile consumerism and human atomization. They omit classical liberalism’s gift of freedom of speech, human rights, equality before the law, widespread prosperity, technology and medical science, and an era of relative peace. Inquisitors no longer torture, witches are no longer burned, women have equal rights, civil life no longer has legally binding theological litmus tests, and historically Christian nations of the West no longer war against each other as they did for centuries.

But as Christians should profoundly understand, the world remains fallen, and even in an era of relative peace and prosperity, people fail to live as sanctified saints or build societies that resemble God’s Kingdom. The founders of classical liberalism rightly thought it a great victory for righteousness that societies could be relatively peaceful, tolerant and subdued, avoiding the zealotries of crusades and holy wars. America’s founders mostly were happy to construct a benign commercial republic, not a theocracy or a holy empire. People devoted to making money generally are less dangerous than zealots seeking to inaugurate God’s Kingdom on earth, often through rivers of blood.

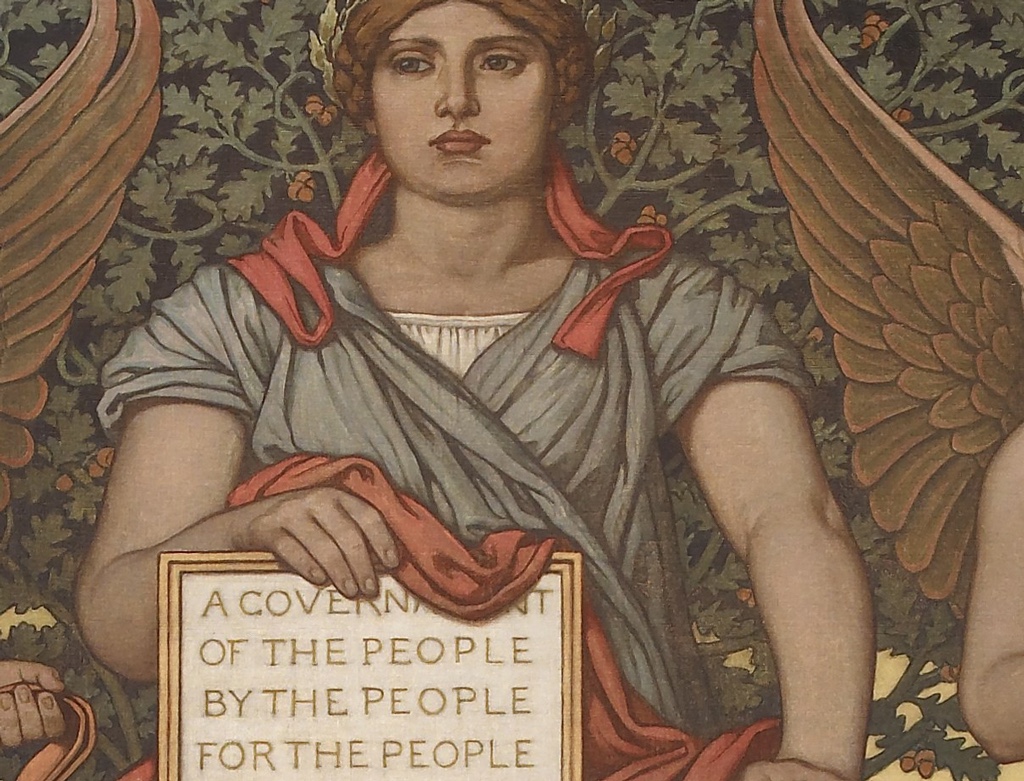

Even commercial republics need spiritual architecture. For America, mostly Protestant inspired but inclusive civil religion has generally served us well. It inhibits holy wars but invites religious inspiration and restrains ideological extremism. It reminds us of God’s watchful Providence and judgment. It summons us to care for the common good and godly human dignity.

American civil religion is different from continental European ethno-nationalist movements that sacralize their cryto-authoritarian politics with garnishes of Christian symbolism. A true cultural Christianity upholds God-given human liberty instead of baptizing coercion or promising unattainable regimes of holiness.

These Catholic integralist-friendly writers are right to lament amorphous humanitarianism, which they describe as liberalism, that pretends to function absent spiritual architecture. True liberalism, sometimes known as Whiggery, classically rests on biblical premises about humanity’s nature and purpose. But unlike integralism or other spiritual utopianisms, it knows the limits of fallen humanity and leaves redemption to God, who, unlike human systems, merits the trust.

Comment by Kerry Wood on November 13, 2021 at 10:52 am

The only quibble I have with your exposition is this statement: “People devoted to making money generally are less dangerous than zealots seeking to inaugurate God’s Kingdom on earth, often through rivers of blood.”

Much of the past 20 years of violence in Afghanistan was driven by economic malfeasance and corruption. Much of the damage done to our environment is from immediate profit motives trumping sustainability. The ongoing Facebook controversies show the hubris and terrible damage to humanity when profit means more than mental health. Therefore, I conclude that ANY and EVERY human system is corruptible and dangerous.

Comment by Marc on November 13, 2021 at 11:13 am

Today’s “liberals” have nothing to do with the philosophy of 18th century U.S. liberals and liberalism. We need to stop confusing the two. Today’s liberals are working to end free speech and the rest of our Bill of Rights. That’s what wokeism is all about. We aren’t allowed to say or even think certain things.

Comment by David on November 13, 2021 at 4:41 pm

No right listed in the Bill of Rights is absolute. If speech and the press were entirely free, there would be no laws against slander and libel. Shortly after the passage of the Bill of Rights (1798), we find the Alien and Sedition Acts that essentially had it a crime to criticize the Federal Government. The “Founders” were not so liberal. Of course, there is the old observation that yelling fire in a theater was not protected speech.

Comment by Miguel on November 16, 2021 at 7:56 am

Author jumps from Catholic integralists and civil religion to jihadism and theocracy. It reflects the almost universal bias and discrimination (inherent) Protestants have of Catholicism. We see you….

Comment by Loren J Golden on November 16, 2021 at 5:06 pm

Miguel,

To put it mildly, the Roman Catholic Church does not have a great reputation among non-Catholics when it comes to the history of Church/state relations.

Comment by td on November 17, 2021 at 5:56 pm

Loren golden, there is plenty of blame to go around here. US protestants have a long history of discrimination against “the catholics”.

Comment by Loren J Golden on November 21, 2021 at 8:24 pm

td,

Yes, there is a history of anti-Roman Catholic discrimination by Protestants in the United States, as well as in many European nations where Protestants have gained the power of crown or parliament. Yet no one at this time is suggesting bringing back a situation where Protestants would once again utilize the power of the state to enforce Protestant doctrine, whereas the “Integralism” that some Roman Catholics are proposing to reintroduce would so utilize the power of the state to enforce Roman Catholic doctrine, much as the Inquisition did from the Twelfth through the Nineteenth Centuries in countries where Roman Catholics were in power.