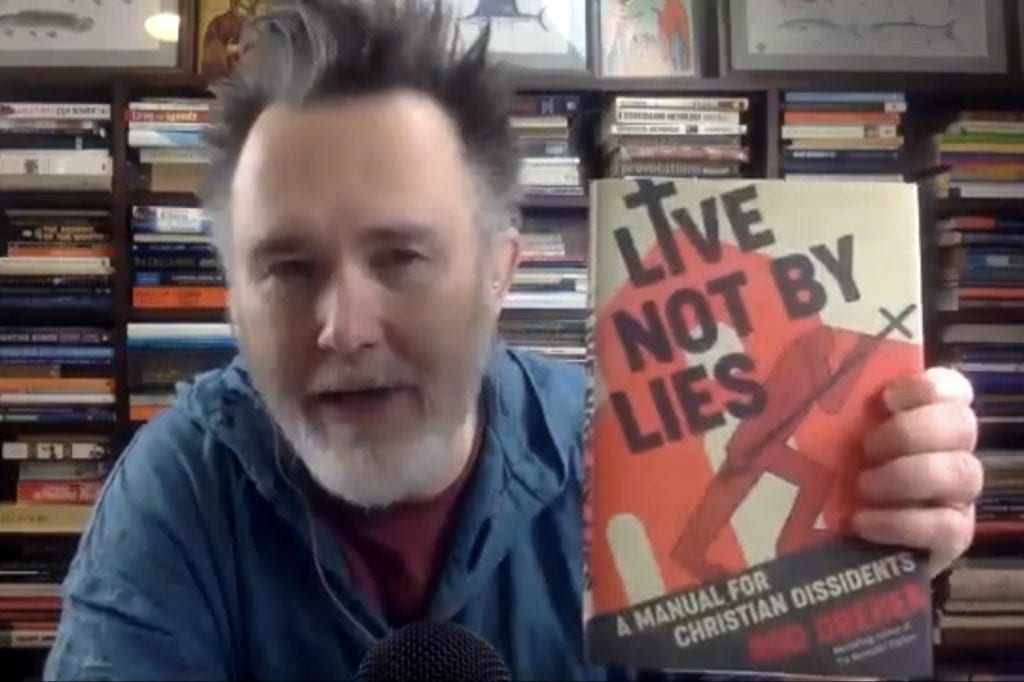

Here’s my chat with commentator Rod Dreher on his new book Live Not by Lies: A Manual for Christian Dissidents, which recalls survival of Soviet Bloc Christians and lessons they offer today. He’s not suggesting our times equal theirs but does propose that their willingness to sacrifice for faith is instructive for all times. It’s a hard but needed message.

Tooley: Hello this is Mark Tooley, president of the Institute on Religion and Democracy, speaking to you today from an undisclosed location in Northern Virginia outside the nation’s capital, with the great pleasure of talking to commentator and writer Rod Dreher about his new book Live Not by Lies: A Manual for Christian Dissidents, addressing how Christians survived under the old Iron Curtain during the Cold War and lessons that their survival offer today’s Christians in America and throughout the West as there is increasing social hostility towards Christianity. So, Rod, thank you so much for joining this conversation.

Dreher: It’s great to be here, Mark. And you know, it’s a very 2020 thing there you are in an undisclosed location. I’m in a very disclosed location here in south Louisiana, and we have a hurricane striking us in about three hours and everybody here is like, yeah, whatever.

Tooley: Like a minor event compared to everything else.

Dreher: Yeah, it does. But no, thanks for having me on. My book Live Not by Lies has been out for almost a month now and it’s doing really well. And I’ve been so grateful to hear good things from Christians all across the spectrum — Protestant, Catholic and Orthodox — who find the stories that the former dissidents from the Soviet bloc tell in this, in my book to be really helpful and clarifying.

Tooley: Well, your book is especially appropriate for us to examine at the Institute on Religion and Democracy, which was founded during the Cold War specifically to express solidarity with persecuted Christians, about whom American churches too often were silent. And often American churches were making excuses for the persecutors. So, tell us a little bit how you relate their struggles and survival to contemporary times for American Christians.

Dreher: Well, you know, it’s something that you have to be careful with because I don’t want in any way to suggest that what American Christians are going through in this country in 2020 that it is the same as what the persecuted church in the Soviet bloc had to endure. We don’t have gulags; we don’t have secret police coming to kick our doors down and to torture our leaders. But there are parallels. And the people who tipped me off to this were people who had come to America and to the West, generally speaking, from the Soviet bloc who escaped communism, but who have lived long enough now to see certain aspects of the totalitarian ethos taking root here and want to warn us about it. For example, they believe that an ideology is suffusing all aspects of life increasingly, especially in major institutions of civil society like universities, the media, corporations, and so forth. And this ideology is making it impossible to speak your mind without fearing that you’ll be fired, that you will be ruined in terms of your personal status, and you’ll be cancelled, as they say. And this ideology has certain aspects in common with Marxism, and what they want us to do is to wake up and realize that one reason we don’t see it as totalitarian or we don’t identify so-called social justice as totalitarian is because it doesn’t have the same aspects of hard totalitarianism, as under the Soviets or as in George Orwell’s 1984. But it doesn’t make it any less totalitarian that it’s coming to us in a softer way and for therapeutic reasons.

Tooley: Often, what is called the “church of woke” is cited as a force that’s inside institutional Christianity, but also obviously is in secular society and in effect is becoming in some ways the new state religion in America, advocating this intolerance and cancel culture that you mentioned. So, in many ways it’s a religious force, isn’t it, that we’re attempting and having to resist?

Dreher: Absolutely. It’s a pseudo-religion in the same way that Bolshevism, and in fact Nazism, were pseudo-religions that appealed to very broken societies in Germany and Russia in the early part of the 20th century. I think that when a society ceases to believe in God, that doesn’t mean it becomes completely secular and believes in nothing. It has to be something that will appeal to the spiritual nature within human beings and to their psychological need for a sense of harmony and a sense of meaning and purpose. Hannah Arendt in her great book The Origins of Totalitarianism, published in the 1950s, went back and looked at Germany and Russia to find out what it was about those societies that made them susceptible to what the totalitarian tried to offer. And she found a number of things that really do resonate with people in our society today. Most importantly, mass loneliness and optimization. She found that the people in those societies coming out of the First World War and in Russia, the Bolshevik Revolution, that people were desperate for something to give them a sense of solidarity, a sense of meaning, and a sense of purpose. And totalitarian ideologies were fit to order. And I think that we see now in this country, so much of this weakness is moving into the churches and is behaving in a parasitic way on traditional Christianity. By turning itself, in some ways, and to an ultra-Christianity, to use the term that Rene Girard used. They’re becoming more Christ-like than Christ himself in terms of standing up for victims. And of course, this is not real Christianity. But we seem in the churches today to be particularly vulnerable to these pills.

Tooley: Now I would be especially familiar with this phenomenon among the Protestant evangelical churches, but so it must be an equivalent among the Catholic and Orthodox churches?

Dreher: Oh sure, yeah. I’m familiar with the Catholic world because I was Catholic for so many years, and you see it in Catholic universities, especially you see it in Catholic publishing houses. I remember going a few years ago to a Catholic university on the east coast and being told in conversation with one of the theologians there that he could not mention, none of them could mention, in class what the Catholic Church actually teaches about homosexuality, or even quote Pope Francis without fear of being hauled up on charges dismissed by the administration. So, that’s how it’s playing out there. In the Orthodox Church, I’m an Orthodox Christian, it’s not as prevalent, but there are rising voices, especially on the east coast and institutions who are trying to turn Orthodoxy into a sort of Byzantine Episcopalianism. So, it’s something that we always have to watch for. But I think the thing that is even more difficult is the way that the people themselves, the laity, are being categorized by the broader culture, by the media culture. And when they don’t hear anything from their leaders from their pastors or other leaders within the churches, then they assume that it’s okay to believe this woke stuff. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve heard ordinary Christians, even those who are part of conservative churches, wonder what in the world are they to think about the new claims for transgender identity because they get zero instruction or guidance from their pastors. We just don’t seem to be able to talk about it in the church and any way beyond sort of a shallow moralism.

Tooley: So, under this “church of woke,” certain issues regarding their human sexuality can be discussed and certain issues regarding race cannot be discussed. I suppose the aspects of American and Western history can’t be discussed, or accepted in completely condemning fashion. Are there other topics that are now a taboo?

Dreher: Those seem to be the main ones. And I, frankly, I’ve been really shocked by how quickly race has rocketed to the forefront of these taboos. You know, when I wrote the book, it was all about sexuality. That was the thing that we couldn’t talk about within churches and in the public square without being demonized. But since the George Floyd killing this summer and the rise of Black Lives Matter, it has been extraordinary the extent to which we can’t even bring a Christian witness to criticize this new ideology. I mean, of course, we should all as Christians be against racism, but Black Lives Matter seems to make it such a, seems to centralize race in a really un-Christian, and even anti-Christian, way. But if we try to push back on that, even from a Christian point of view, we get smothered by people saying that deep down, we’re racist. And I think that I’ve seen it happen so often that well-educated and well-informed Christians seem to fall silent when they’re accused of racism. We’re so used to being called bigots from the homosexual side, pro-gay side, though we didn’t see the race thing coming at all. I have to tell you, Mark, that a few years ago, I should have seen this coming. I was invited to give a talk out at the Christian studies center at the University of Virginia about my book on Dante, and they all knew that I was about to start working on a book about the Benedict option, and they were eager to have me back there to interview them about some of the really innovative and interesting things they were doing as a Christian community. And before I was able to get back there, there was a sermon given about Black Lives Matter at the Intervarsity Christian Fellowship annual meeting, and I criticized the young woman giving the sermon. I said that this is racialized in the gospel in ways that I find to be contrary to the gospel. The fact that I criticized her on my blog ended up getting me blackballed at this study center. And I couldn’t figure out what it was. And it turns out that most of these young people, they’re all white evangelicals, almost all white evangelicals, were so down with pumping out so-called critical race theory that they wouldn’t even talk to someone who criticized it, a fellow Christian who criticized it. And I found it to be absolutely extraordinary. But I should have realized that, this may have been 2016, but I, this, was a presentiment of what was to come for all of us.

Tooley: Yes, and many, not just young Christians, are susceptible, because when they address these issues, too often there are not constructive, theologically deep Christian resources that they can look to.

Dreher: Yeah, that’s true. And again, it’s an absence of leadership. I mean, one thing that helped me a lot as I was working on this book is to think about the difference between social justice, as it is called in our secular culture today, and a Christian idea of social justice. The term itself, it’s Christian. I believe it originated with the 19th century Jesuits. Now for Christian social justice, society is one that is constituted along biblical lines, and that makes it possible for individuals to live up fully to what God has made them to be. What God has called us to be. And it may intersect with secular ideas of social justice, but often it doesn’t. And the secular idea that’s so strong today, social justice as a matter of equity among groups, identity groups. And it should be pretty clear how that clashes with Christian ideas of social justice. When I was looking at the so-called social justice warriors and how they, how much they have in common with the early Bolsheviks in late 19th and early 20th century Russia, I was really starting to see how much they were so moralistic and so apocalyptic. But they divided the lines between good and evil between people according to their classes. And for the Bolsheviks, it was social class, and for the SJWs, its identity groups race, sexual identity, and so forth. But they work along the same lines to identify the human person as primarily, or even solely, with their identity class. And that is a tremendously important distinction. Solzhenitsyn, as you know, said that when he came out of the gulag the thing he learned was that the line between good and evil goes not between classes. Social classes become the middle of every human heart. This I think is what true Christianity can bring to the social justice discussion, but these voices who espouse this are either too timid, or they’ve been silenced.

Tooley: So, as you say, Christians who survived in the old Soviet Union, or under the old Eastern Bloc European regimes, what they faced certainly was exponentially greater than what Christians face today in America. Nonetheless, there are instructive lessons from their example and their survival. So, as they faced tremendous pressure from their government, and from there subverted churches, and from their whole surviving culture, what were the secrets of the survival of their Orthodox faith?

Dreher: That’s what the whole second half of my book is about, just sitting down with them and getting their stories so we can apply them to what we’re facing. One of the most important things I learned was the importance of small groups. I dedicate the book to a Catholic priest named Father Tomislav Kolakovich. He was a Croatian priest who was doing anti-Nazi work in Zagreb in 1943 when he got a tip that the Gestapo was coming for him. He escaped the country, went to his mother’s homeland Slovakia, adopted her last name Kolakovich, and taught at the Catholic University. He told the students that the good news is the Germans are going to lose this war. The bad news is that by the time it’s over with, the Soviets are going to be ruling this country, and the first thing the Communists are going to do is come for the church. So, he prepared them by forming small groups of really dedicated Catholic students who would come together for studying scripture for prayer, but also to study the problems in their society and deliberate among themselves about how to act to defend the church in the coming darkness. He spread these groups all over Slovakia. The bishops were against it. They told him like you really are alarming people, things won’t get that bad, but Kolakovich understood the Soviet mind. Sure enough and the Iron Curtain fell over Czechoslovakia. The only churches that were allowed to work as churches where the underground groups that Father Kolakovich had founded, because the communists came after the formal structures of the church, came after priest Kolakovich, which is the best example in his group. But I heard this over and over again in Russia, in Poland, and in Slovakia that small groups and small fellowships were important for Christians, so they would also have a place to experience a sense of freedom from the oppressive state. The most important lesson though, and is in the last chapter of the book, it’s about the importance of suffering. I heard this over and over again from the people I spoke to, most powerfully from a Russian Baptist pastor standing in the street in Moscow in the snow. He said, “You go home and tell Americans that if you’re not prepared to suffer than your faith is hypocrisy, you’re not going to make it.” Their point is that if you’re not willing to endure slander, maybe losing your job, losing your freedom, ultimately your life for the sake of the gospel, then you won’t be able to withstand what the totalitarian system is going to throw at you. And this is something that hit me really hard as an American Christian, because we’ve had it so easy for so long. And so much American Christianity across the churches is what Christian Smith, the sociologist of religion, calls “moralistic therapeutic deism.” In other words, it’s all about making us feel comfortable and happy. This is precisely the kind of pseudo-Christianity that is going to be crushed by what’s coming. And this is the most emphatic warning from the Christians who lived through hard totalitarianism, is that if we can’t suffer, we’re not going to kind of survive this.

Tooley: So, for example, the prosperity gospel probably will not fair very well?

Dreher: You know it won’t fair well at all. And not only the prosperity gospel, but the sort of Christianity that so many of us have a church on Sunday, which is not necessarily bad, but it’s kind of moralistic, maybe helps us feel better about getting through the day and all that. It’s okay. But that’s not the same thing as the gospel itself. And if we are not looking to the church, the church of the martyrs, whether it’s going back to early Christianity or studying the martyrs in our own time and other places around the world, particularly in the Soviet bloc, then we’re completely, our imagination just can’t, we can’t comprehend what it would be like to lose status. To suddenly find ourselves, because we’re Christians, pushed out of professions. Our kids pushed out of universities and so on. You know, I tell the story in the book about Vaclav Havel, who was not a Christian, but he was a good man. A good liberal. I mean that in the best sense. He tells a story about the shopkeeper, the “little green grocer,” and under communism, who decides one day not to follow the other shopkeepers in putting a sign in his shop window that says “Workers of the world unite.” You know, the communist slogan. He says, “I’m not going to put it there. I don’t believe in this. I’m not going to go along.” Well, what happens to him? He loses his shop. his kids can’t go to college, he’s out of work, and on and on and on, because he’s defied the ideology, the ruling ideology. But what he has done by taking a stand for freedom, says Havel, is he’s gained an important moral victory, because he has shown that it is possible to live not by lies. It is possible to live as an honest man in this dishonest system. And if one man can do it, then he will perhaps inspire other men and women to do this. This was the experience of the underground church in Russia. By the way, I spoke to a man who was one of the late dissidents there. He was sent to prison in the 70s because of his work in his 20s as a Christian in Moscow. And he said that so many people came to them, their little small Christian group in Moscow in the 70s, because they were completely burned out with Soviet society, and they were desperate to join somebody who had some reason to live and to live in truth. The fact that these Christians are willing to stand for their faith and suffer for their brave, send a message to so many lost souls there in Russia, that these people have something worth living for.

Tooley: Finally, Rod, you mentioned the priest who was confident that the Nazis would be defeated. I assume he was also confident that communism itself would eventually pass. It seems key to the Christian idea that there is always hope that whatever we’re enduring, it too will pass, and God’s kingdom always prevails in the end, too. How do we as American Christians incorporate this confidence, and how do we live out our faith?

Dreher: You know, it’s funny Mark, not one of the Christians I talked to over there believed that communism was going to end in their lifetimes. They knew it would end at some point. But they didn’t think they would live to see it. They did what they did because it was the right thing to do, because as followers of Jesus Christ, they knew that they had to live in his truth no matter what it cost them. And they were telling me that look, don’t assume that everybody over here was like that. Most people, even in the church, conformed because it was so hard not to conform. But if you believed, as we did, you knew that you had no choice. That you had to be willing even to give your life for the sake of Christ. I think the lesson that we should take from them, Mark, is that we shouldn’t be optimistic. We don’t know how long this is going to last. If we’re optimistic, we think everything’s going to work out in the end. And let’s not worry about it. That can be really unrealistic and can give you some false hope about what to expect. Rather, I think we should be hopeful for as Christians, our hope tells us that things might work out in the end, and ultimately in the fullness of time they will. But even if we don’t live to see it, if we join our suffering to Christ, then the Lord can use that suffering for our redemption. Their attention of others, and that is our hope that our suffering has meaning, has ultimate meaning. I had to tell this story in the book, Mark, about this guy I mentioned to you who was in prison and really at a low point in the gulag, in solitary confinement, really beginning to wonder whether God had abandoned him. And he had spent his time in prison prior to that, when he was in with general inmates giving testimony and trying to lead some of the hardest men in Russia to Christ. One day he was awakened from his sleep by an angel. And he said the angel showed him a vision of man, a prisoner, walking, being led away by guards from behind with his hands, being led to his execution. He couldn’t figure out why he was allowed to see that. And then over and over again every night he was shown a different man in the same way by an angel. And he’s telling me this in the lobby of a luxury hotel in Moscow last fall, and he starts to cry, and he says “The Lord showed me. I came to understand that each one of those men that was being led to their death are men that I’d witness to, and they were going to be with him in paradise because I was there to preach the gospel to them. And suddenly I understood why the Lord had allowed all this suffering to come into me because he had his purposes.” I don’t think that any of us will ever suffer that kind of persecution that he did. I hope we don’t. But whenever any small thing happens to us, we have to keep our eyes on the fact that the Lord can use this to bring us individually to deeper conversion, and also to bring the world to know him and to serve him. That has to be our hope.

Tooley: Rod Dreher, author of Live Not by Lies, a Bangalore for Christian resistance, thank you very much for a challenging and inspiring interview.

Dreher: Thank you, Mark, for having me.

Comment by Douglas E Ehrhardt on October 30, 2020 at 7:43 am

Great interview . The killing of George Floyd was the only problem. George killed himself.He was dying if an overdose when the police arrived.Spent years working in drug treatment. As soon as I saw his behaviors I thought ,wait for the autopsy.And then there was the bodycam. Dead man walking. Made for a great excuse for looting and rioting though.

Comment by Search4Truth on November 6, 2020 at 9:52 am

While we do know the of the story, we still cry out with the saints, “How long, Lord?” We are now awaiting the results of the election and the very real possibility of the enaction of the Equality Act. If/when this happens, the experiences you cover in your book will become all too real in this country also.

Comment by Search4Truth on November 6, 2020 at 9:53 am

“the end of the story”

Comment by Rocky on March 18, 2021 at 6:23 pm

Mark, loved the interview. Just loved it because now it’s March 2021 and so much of this is happening at an accelerated pace. We’ve joined a non denominational, Bible based church that preached this Gospel and all the Bible. So much different from my old Methodist Church and BETTER!

Only one criticism, someone should have proof read the interview for Mr. Dreher’s wording. It was pretty difficult to follow him due to the choice of written words and misspelling, etc.

God Bless,