Video of Brandt Jean’s profound extension of forgiveness to Amber Guyger during his brother Botham’s murder trial has gone viral. Rightly so. But, some have lamented that the boys’ mother Allison Jean’s response to her son’s murder should have done so as well. And yet it hasn’t. That’s a shame, because Mother Jean was pretty incredible. Like her son, she spoke with a bearing and strength that I only flatter myself to think I’d be capable of in a similar situation. But whereas Brandt spoke eloquently about grace, Mother Jean gave a bracing amen-and-hallelujah sermon on justice. Both are essential to a Christian understanding of forgiveness.

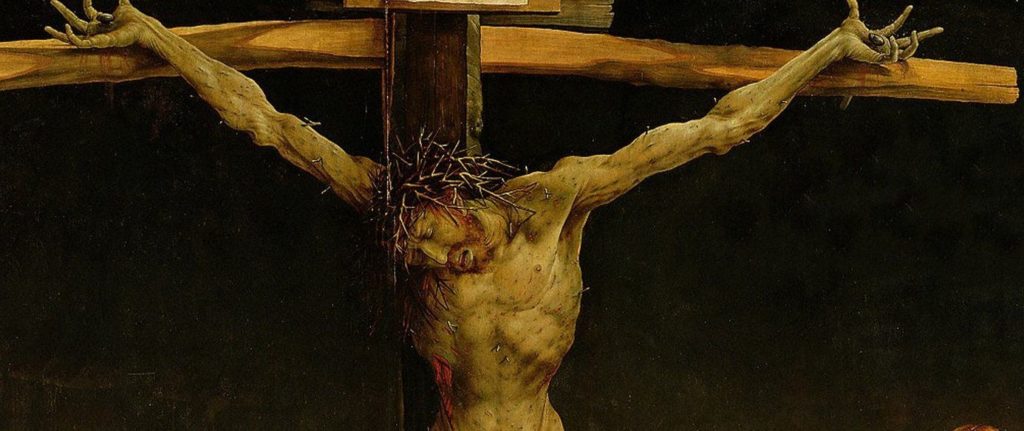

IRD’s Faith McDonnell has already written about Brandt’s extraordinary witness. I want to focus on where Brandt’s and his mother’s witnesses intersect. Taken together the Jean family statements give a more complete understanding of the gospel than either can in isolation. Much of the public response appears to grasp this. Not everyone has been exactly cock-a-hoop about Brandt’s clement embrace of Guyger. As is commonplace nowadays, some of the criticism laments the specter of white supremacy supposedly evident in the public adoration of Brandt. Why, some wonder, is it always blacks forgiving their white assailants and not the other way around? Other—more temperate—criticism is grounded in the concern that Brandt risks distorting the message of the cross by elevating grace over justice, focusing only on the forgiveness of Christ while forgetting about his scourge-pulped body. The worry is that too many of us—including or especially too many of us Christians—are overly eager to focus on Brandt’s magnanimity at the expense of Mother Jean’s pain.

I have fretted elsewhere that Western Christians traffic in increasingly maudlin theology. We believe in God, but this God we believe in is sanitized and sentimentalized. He is a God of love, fine, but our understanding of this love is grounded in a soil untilled by the biblical witness. This has had a devastating effect on our theology and consequent moral and ethical frameworks—including our understanding of forgiveness.

The Oxford professor (and Providence contributing editor) Nigel Biggar helpfully describes Christian forgiveness as proceeding in two discreet steps, or moments. These moments map quite well onto the grace and justice embodied respectively by Brandt and Mother Jean.

The first step is “forgiveness as compassion.” In one sense, it has nothing whatsoever to do with the offending agent, and everything to do with the victim. Forgiveness as compassion is where the victim allows her resentment of the crime against her to be moderated by the acknowledgment of certain truths. One of these truths is that none of us ever stand opposite another human being as wholly righteous versus unrighteous. We are all of us sinners. In each of us, our personal histories and our depraved or weakened wills marble together, leaving us more or less equipped than others to resist common temptations, common pressures, common fears, and common appetites. Sometimes, some of us are fated to find ourselves trapped in situations where only a superhuman moral heroism could keep us from committing terrible abuses against our neighbors. This does not excuse the abuse. It only reminds us that we rarely know the entire story. We can—and must—respond to our abuser’s actions, but we cannot read their heart. Empathetic humility reminds us that but for the grace of God, the offense might our own. Forgiveness as compassion issues in the kind of sentiment exhibited by Brandt: a desire for the offender’s good, a wish that they would not cleave to their offense, an openness to the possibility of reconciliation. This is a burden, to be sure. But, as Biggar notes, even victims, too, have responsibilities. One of them is to acknowledge truths like these, even in the midst of raw anguish.

But while this first moment of forgiveness is unilateral, the second moment is not—must not—be. “Forgiveness as absolution” is perhaps what we most commonly think about when we talk about forgiveness. It is the moment in which “I forgive you” is stated and reconciliation becomes possible. Forgiveness as absolution has everything to do, up front, with the offending agent and their own credible articulation of remorse, repentance, and an obvious and credible demonstration that they have turned away from their wrongdoing and have no intent to do further harm. Indeed, absolution offered before the wrongdoer has repented involves a profound violation of Christian love. It is a violation in two ways.

First, it is unloving to the victim of the crime by denying their right to vindication—to have their value accounted for and the offense against their value acknowledged. Not even the victim of a crime is free to offer absolution to their unrepentant offender. Every human being is loved and valued by God. As Christians we are to love and value what God does. So, we are to love and value ourselves. We have no right to deny our own God-given worth by allowing offenses against us to be absolved without the wrongdoer acknowledging the offense.

Second, to absolve an offense before repentance is offered is unloving to the offender. It risks short-circuiting that process by which the offender can—through the grace of guilt and sorrow—come into full recognition of the violation they have committed, acknowledge their sin, repent, and turn from their wrongdoing. To be sure, forgiveness as compassion can be a part of that process to bring a wrongdoer to repentance. But absolution can only ever be the culmination of that process.

As I see it, Brandt’s testimony gets the sequence of forgiveness right. Importantly, his offer forgiveness began with a crucial caveat that did not make it into every video-clip I have seen. But in the fuller version, he prefaces his statement with the words “If you truly are sorry…”. This qualification links together the possibility of not just forgiveness as compassion but, perhaps, of absolution as well.

I do have one criticism of Brandt. When he—compassionately—says to Guyger “I want the best for you” he adds that he doesn’t even want her to go to jail. That is too much. He is right, of course, to not want to “see her rot in prison.” But even when we are repentant, consequences most often must remain. While even retributive justice ought to aim at restoration, restoration is not the only aim. Important, if secondary purposes of punishment such as restitution (including the vindication of victims), protection, and deterrence are still in play. Taking the Divine cue, human judgment ought to be tailored to promote the goods of restraint, repentance, and a changed life. In this sense, it might well be to Amber Guyger’s own good that she be punished. As Mother Jean said, prison will hopefully be the crucible in which Guyger fully confronts herself.

Brandt’s critics are right that we often make a hash of forgiveness. They are wrong to think Brandt has. They are also wrong if they think that the hash is always made by those over-eager to absolve prematurely. For every person too quick to forgive, there is on the other side a Javert or a Shylock demanding that no quarter be given. Both imbalances are an offense to the cross.

Also wrong are those who think it is only ever blacks who forgive whites. The perception, if honest, is noteworthy and deserves to be addressed. But even a cursory google search proves the perception false, yielding such stories as those of Kevin Ramsby, Mandy Bass, and Debbie Baigrie. That none of these stories went viral does not make them less true. Indeed, one of the most audacious examples of forgiveness came before the social media age. Reginald Denny, whose brick-shattered skull was broken into a hundred pieces, forgave his unrepentant assailants after they dragged him from his truck and brutalized him in the midst of the LA riots.

None of this is meant to be a play at one-upsmanship. It is only to suggest that we take care to check our perceptions. It would appear that even in the midst of so many divisions in our broken society, human beings of every kind—all of them made in the image of God—have a desire to not be so divided after all. Even as we stumble our way through our partially efficacious attempts at grace and justice we have cause to look forward in hope to that great and terrible day of perfect judgment.

—

Marc LiVecche is the executive editor at Providence: A Journal of Christianity & American Foreign Policy and the just war and Christian ethics scholar at IRD. He is currently in Oxford, where he is the McDonald Visiting Scholar at the McDonald Centre for Theology, Ethics, & Public Life at Christ Church College. His book, The Good Kill: Just War & Moral Injury, is under contract with Oxford University Press.

No comments yet