The debate over illegal immigration has intensified recently after a massive increase in unaccompanied minors crossing the U.S.-Mexican border. U.S. officials and lawmakers are now struggling to deal with an estimated 52,000 Central American children, mostly from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. The motivation behind this mass migration remain unclear, but the leading causes appear to be gang violence, poverty, and the belief that the federal government is issuing “permisos” granting citizenship to undocumented children. This most recent surge adds a new, unique layer to the illegal immigration debate, with some advocating for their deportation and others advocating for amnesty.

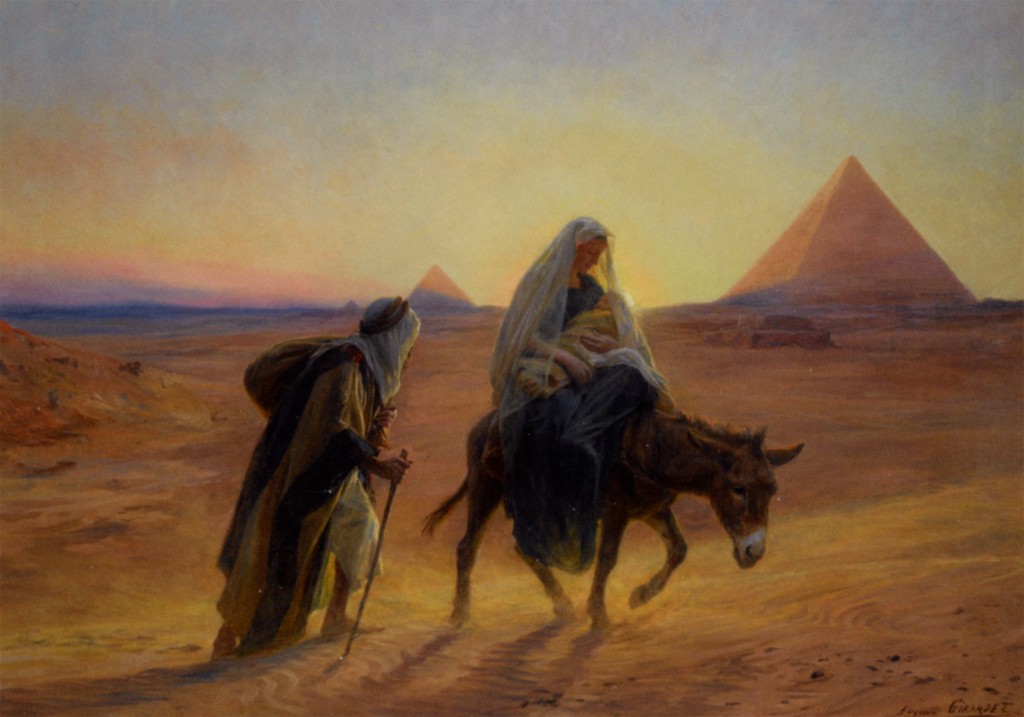

In an opinion piece for Religion News Service titled “Christians worship a child who fled violence in his home country,” the president of the Episcopal Church’s House of Deputies Rev. Gay Clark Jennings makes the case that Christians should support granting asylum to the children because Jesus Christ himself was a migrant fleeing violence. “As politicians focus on midterm elections rather than on children in crisis, it’s worth remembering: Christians worship a child who fled from violence in his home country… Just like parents in Central America who are sending their children away, Mary and Joseph took great risks so their son could survive.”

There is much I agree with in Rev. Jennings’ piece, and much I disagree with. What stood out to me above the political and personal elements of the op-ed was the inference that Christians should care for these children because Jesus was in a similar situation. Rev. Jennings is certainly not the first person to articulate the general idea; Southern Baptist thinker Dr. Russell Moore went even further in saying that Jesus was an illegal immigrant. But after considering the issue, I’ve come to the conclusion that Jesus’ immigrant status is simply irrelevant to today’s immigration debate.

To begin with, the circumstances of Jesus’ migration and modern-day illegal immigration into the United States are not identical. Since Egypt and Judea were both Roman provinces, Jesus wasn’t even an “immigrant” strictly speaking, and contra Dr. Moore, Mary and Joseph likely wouldn’t have been breaking any laws. There is also no indication that Jesus was one of millions of people in a mass migration, or that Egypt had in place any sort of social welfare that might be strained by his arrival, or that Jesus jumped the line while others were in a waiting list, or that any of the other morally murky factors of today’s immigration debate were present.

But let us suppose that there are at least significant enough similarities to entertain the comparison between Jesus’ flight to Egypt and the Central American children crossing our borders. I still tend to be skeptical of demographic appeals to the life of Jesus for political or ideological reasons. Yes, Jesus was at one point a migrant. But as Michael Novak once pointed out, Jesus was also a small businessman. For some reason, that factoid never really caught on in liberal circles.

Jesus was also at various points: a carpenter, a laborer, a winemaker (of sorts), a healer, a son, a brother, a bachelor, an unborn child, an infant, a teenager, an adult, male, homeless, a traveler, a death-row prisoner, a Jew, a Roman subject, a teacher, a student, and a rabbi. Which of these identities should we stress, which should we contextualize, and which are irrelevant?

Obviously, if there was a national dispute in which a major player was a carpenter’s union, no one would seriously say we should favor one side because “Jesus was a carpenter!” I also assume that a female priest like Rev. Jennings would disapprove of the importance of Jesus’ maleness in the priestly traditions of the Catholic and Orthodox Churches. And what about when Jesus’ “identities” conflict? For example, you have those claiming that “Jesus was a Palestinian,” but also those who remind us that Jesus was a Jew. Gosh, now how am I supposed to boil down a complicated, multifaceted international conflict into a soundbite?

Put simply, my pet peeve is “Jesus-as-ammunition,” where personal traits about Jesus are stressed solely to score points in a debate. We see something similar with historical figures like Adolf Hitler, where there are endless debates whether Hitler was conservative or liberal or a Christian or an atheist. For every serious historian involved in these debates, there are probably a hundred partisans who just want to smear their opponents with accusations of Nazism. Jesus-as-ammunition is the prettier side of the same coin, conferring holiness by association instead of guilt by association. Either way, it’s just as intellectually hollow.

Logicians refer to this way of thinking as the association fallacy. My mother was an immigrant. So was Hitler. So was Jesus. So were the 9/11 hijackers. So were some of the 9/11 firefighters. Immigrants, in short, are people; people with the full spectrum of human emotions and tendencies. To support a political position affecting millions based on personal admiration or animus towards a specific immigrant– even the Son of God– is to substitute rationality for sentimentality.

Let’s all be completely honest with ourselves. Suppose, in some alternate reality, the Gospel of Matthew was devoid of any mention of the flight to Egypt. Does anyone really believe that Rev. Jennings would be less likely to champion asylum for 52,000 displaced children? Does anyone doubt that conservative Christians would be just as skeptical about such proposals? The underlying principles, beliefs, and life experiences informing our stances do not rise and fall on whether or not Jesus crossed a border at some point in his life.

I don’t doubt that there are probably a few people who would be more likely to empathize with immigrants after learning that Jesus was one. However, those people are operating under a fundamentally unchristian approach that needs to be corrected. Jesus doesn’t want us to care for the poor, the strangers, and the sojourners because they look like him, act like him, or have the same life experiences as him. He wants us to do so because it’s the right thing to do. If we really want Americans to honor Jesus, remind them that whatever is done to the least among us is done to Jesus Christ (Matthew 25:40), and urge them to emulate Jesus’ actions towards outsiders (John 13:15) rather than fixating on his earthly qualities.

There are plenty of strongly-worded commands in the Bible to care for the strangers and sojourners among us (Leviticus 19:34, Exodus 23:9, Hebrews 13:2). Any Christian must approach the immigration debate with these verses in mind, even if they consider them in light of those verses stressing the rule of law (Romans 13:1, 1 Peter 2:13). It is true that too many Americans, including self-described Christians, do not approach the issue with compassion for illegal immigrants. But we need not sacrifice our God-given reason in our zeal to correct their error.

Comment by matt860 on July 28, 2014 at 10:02 am

Hi Alexander: Thanks for your article. I agree — we must balance our care for the stranger with our own immigration laws and how we enforce them. Here’s a quote from a piece written by a Catholic priest in the diocese of Arlington, VA: “In

the first place, the current immigration laws must be seen in their proper

context. They are human, positive laws,

so called because they are “posited” or put forth by a human legislative authority. Antecedent to the positing of particular

human laws, there is the moral law, or natural law, which is man’s

participation, through right reason, in the eternal law of God. … the

natural law itself does not specify what precise juridical conditions are to be

placed on the exercise of the right to immigrate. However, according to the natural law,

political authorities are to make a determination, for the sake of the common

good, as to what those juridical conditions are to be. To the extent that the particular human laws

setting forth those conditions are just, that is, in accord with right reason,

they are human laws that have a basis in the natural law and are morally

binding. Note that the law or set of

laws at issue may be far from the ideal law or set of laws; it suffices simply

to be a reasonable determination in furtherance of the common good.” see http://www.arlingtondiocese.org%2Foutreach%2Fdocuments%2Fillegal_immigration.docx&ei=3FTWU4zJK6PLsQSM0YLwBg&usg=AFQjCNEQ-KW__hq5IY8V6B_xtwG9x02PMg