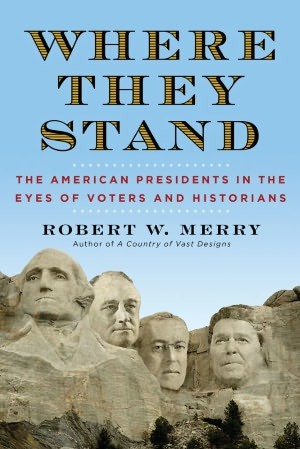

Monday evening I attended a talk at “Politics and Prose,” a Washington institution, by “National Interest” editor Robert Merry, author of “Where They Stand: The American Presidents in the Eyes of Voters and Historians.” Joining the presidential ratings game, Merry tries to assess former chief executives based on what voters thought of them rather than relying exclusively on what later historians decided. Merry ascribes success to presidents who managed to achieve election twice while also ensuring their successor came from the same party. Such presidents include Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Jackson, Lincoln, Grant, McKinley, both Roosevelts, and Reagan. He also has special regard for Polk, about whom he wrote a biography, since Polk achieved so much while declaring from the start he would not seek reelection. Merry readily grants that rating presidents has no finality, and writers will draw their own evolving judgements until the end of time.

Why do Americans attach so much importance to their presidents? For better or worse, they symbolically serve as the high priests of American civil religion. Even Americans who oppose a particular president still expect him to fulfill certain priestly duties that affirm the history and principles of the republic. Washington of course was the first such high priest, a role he created masterfully. Jefferson and Lincoln provided the civil scripture that defined American democracy. Generals who became presidents such as Jackson, Grant and Eisenhower validated civil religion by their sacrificial service on the battlefield and later in the White House. The most popular presidents have fully lived up to their priestly roles. As Eisenhower would later grouse, FDR spoke via radio as though the voice of God. No wonder he was elected 4 times and had he lived, certainly could have gained a fifth term.

This symbolic priestly role for presidents obviously should not be seen as a substitute for faith in and worship of the authentic Deity. Many Anabaptist wannabes irritably denounce any reference to civil religion as idolatrous. But civil religion, in its proper place, serves a legitimate public need for transcendent moral purpose to guide the state and reassure the people. Absent it, or a state church, government operates in a moral and spiritual void. The totalitarian horrors of the last century were one alternative to democratic civil religion.

It’s no coincidence that most of the most successful presidents who preformed their priestly roles so well were themselves fairly serious in their faith and attracted to the pageantry and devotions of church life. Washington, Jackson, Lincoln, McKinley, the Roosevelts and Reagan were sometimes publicly vague about their faith, as politics sometimes demands, but were privately serious. Jefferson, a Unitarian who commonly attended Anglican churches, thought religion essential for morality. Madison, perhaps more theologically orthodox, thought likewise. Grant attended Methodist churches much of his life and spoke the language of 19th century faith, professing a conversion of sorts on his death bed.

All of these presidents were shaped by Mainline Protestantism, which provided the framework for most of America’s civil religion. With the Mainline now in its 5th decade of collapse, and the Episcopal Church, once the mother of presidents, now embracing transgenderism, it’s not apparent what will replace it as the new mediator for American political priestcraft. Maybe a combination of evangelicalism and Roman Catholicism will together perpetuate the tradition.

Comment by Campbell Marlene on July 10, 2012 at 12:08 pm

Well, that is too bad, as both evangelicalism and Roman catholicism believe in absolutes, sometimes avoiding the spirit of the Christian message. This can be dangerous as well.