The story of Methodism is larger than often imagined. For many years the story was told as though it began and sometimes even ended with John Wesley. He repeatedly told the story this way himself. But Methodism was always bigger than Wesley. The story is actually one of international scope, of war-fatigued nations and peoples, of historical memories both good and bad, and of men and women swept up by the Holy Spirit in seemingly random outbursts of revival over the course of decades. Those who encountered this dynamic work of the Spirit often spent the rest of their lives in wonder, just trying to describe what happened.

Our story begins not with Wesley, born in 1703, but earlier with the Glorious Revolution of 1688. It could easily start before that time, but the Revolution of that year ended – for the most part – the struggle caused by shifting cultural, political, and ecclesiastical power in the centuries following Henry VIII’s departure from Rome, or when the church in England became the Church of England. This was a watershed moment. It was at the Glorious Revolution, named quite blatantly by those who claimed victory, that Protestant monarchs William and Mary unceremoniously replaced James II, a Roman Catholic. What was odd about this is that new monarchs usually replace dead ones, or even defeated ones, and James was neither. He was absent.

James was the son of Charles I and brother to Charles II. His royal pedigree was unimpeachable. But he had embraced the Catholicism of his mother rather than the Protestantism of his martyred father. England by the late 17th c. had had enough of religious strife and so the support that he needed to reign as monarch evaporated. This strife was behind the beheading of Charles I earlier in the century after a series of civil wars that led to his defeat and the rise of Oliver Cromwell and his Puritan-inspired Commonwealth. But that eleven-year experiment with monarch, bishops, and Prayer Book banned was of little success. The monarchy was restored in 1660. But in a few decades the fragile balance that held this peace together was beginning to fray. It’s hard to hold together a Protestant establishment, including its state church, when the one at the top appears to be playing for a different team. And so at the invitation of Parliament, William and Mary acceded to the throne. By 1701 the laws of the land mandated that only Protestants will ever do so.

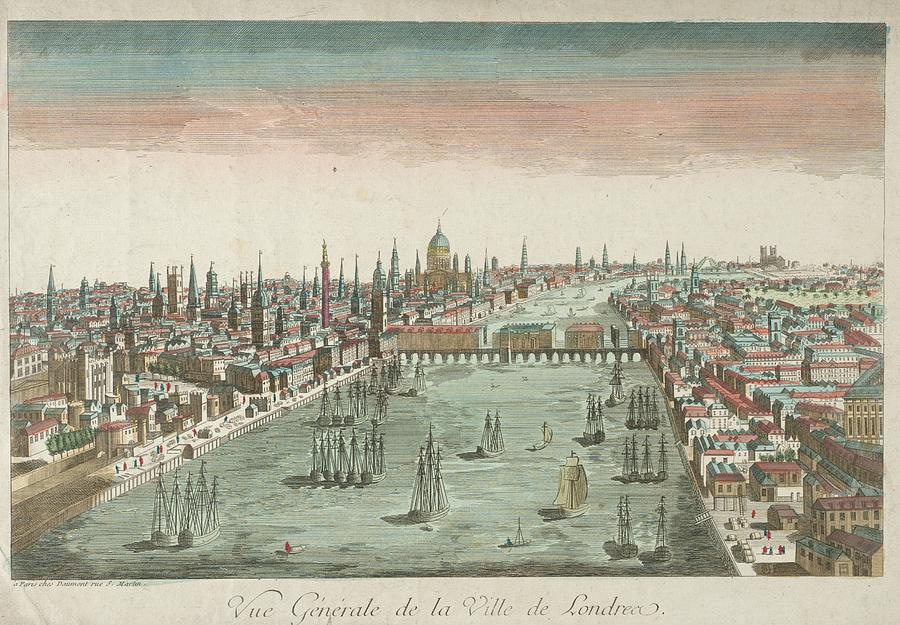

The struggles of the 17th c. changed England and led to a deep-seated desire in the English heart to restore that which had been lost. But they weren’t interested in simple mimicry. That alone wouldn’t do. So as this period unfolds, the English embraced a vision of progress that can be described as restoring the best of the past in the present. In the political realm, this meant restoring the monarchy with the safeguards of Parliament. In the religious realm, this meant restoring the order of the church, its liturgy, its structure, and taking their cues from the good and great of church history, particularly the early church fathers. Even their architecture reflected this view of progress, taking its direction from ancient Greece and Rome. Restoration was the order of the day.

Continue reading at Firebrand here.

Ryan Danker is the director of the John Wesley Institute, publisher of Good News magazine, and associate lead editor of Firebrand.

No comments yet

Leave a Reply