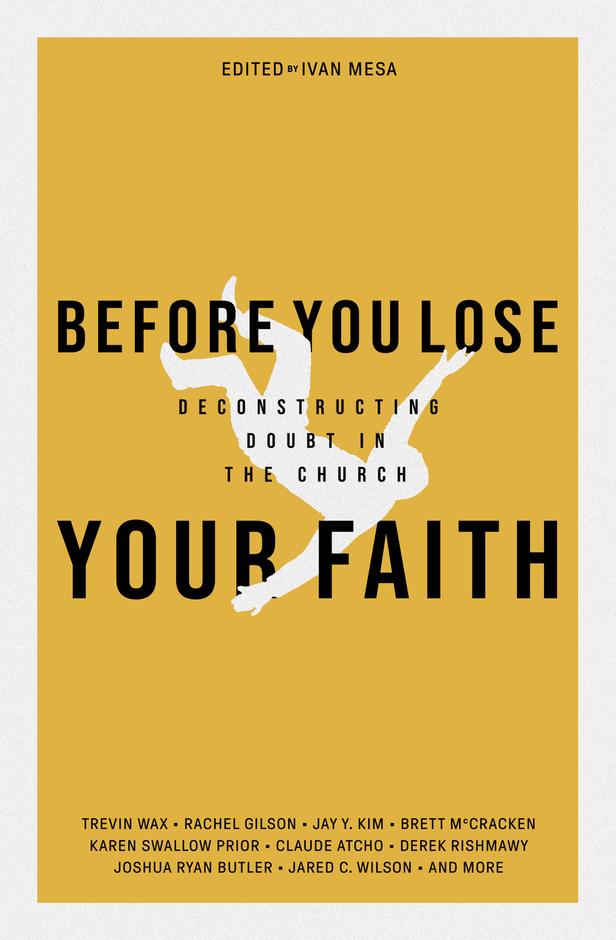

Before You Lose Your Faith: Deconstructing Doubt in the Church is a collection of 15 short essays recommendable to precocious youth group attendees and older believers alike. It compellingly defends orthodox Christianity against some of the most common reasons for leaving the faith; from appeals to science as the only truth to the replacement of religion with watered-down spirituality to worship of politics. Conversational in tone, many of the essays felt like those discussions one would hope to have in a church or Christian college.

Importantly, the book is published by The Gospel Coalition (TGC), an international network of Reformed evangelicals associated with Pastor and Author Tim Keller. They often advertise as community churches or non-denominational, yet hold to a specifically Calvinist belief, sometimes identified as “Young, Reformed and Restless.” Though deeply in the Reformed tradition, many eschew denominational heritage and prefer simply identifying as orthodox Christians. For example, the words “Protestant”,“Reformed” and “Calvin” appear nowhere and “Presbyterian” offhandedly once despite the strong Calvinist influence. This “simply orthodox” framing causes disagreements with Neo-Calvinist theology to be framed as disagreements with orthodox Christianity. Though most of the essays have value regardless of denominational affiliation, there were two that were overly oriented from a new-calvinist framework.

In “Don’t Deconstruct – Disenculturate Instead,” Fellowship Denver Church Pastor Hunter Beaumont argues that American culture and Christian theology can be conflated, so we must “disenculturate” ourselves to see the true Gospel. True enough! Yet I’m less certain of the possibility of anyone really disenculturating themselves and disagree with Beaumont and TGC more broadly about how to save Christianity from culture.

Beaumont points to the work of missionaries as a model for disenculturating; to transmit the Gospel to a new culture, he argues, one must be able to separate the kernel (true religion) from the husk (human culture). Once you learn to disenculturate you will see when a church’s culture is shaped by the Gospel, not vice-versa. “So cling closely to the Gospel and loosely to religious subculture” and so that you can “differentiate what parts [of Christianity] to keep and what to let go.”

Yet Beaumont also recognizes that there’s no such thing as a non-cultural expression of Christianity: “Disenculturation shows us it’s possible to differentiate the gospel from culture, but it doesn’t mean the gospel can be experienced without any culture.” But this presents a paradox: how to determine what’s truly divinely inspired if our theology is always colored by our culture? If there is no theologically objective viewpoint, who judges?

Roman Catholics answer this question with appeals to Papal authority, but for Protestants that doesn’t work. Instead, Lutheran, Anglican, Methodist and Reformed Christians can look to the small-c catholic tradition for authentic expressions of Christianity, in form and content. This means church culture should be ordered around ritual, liturgy and sacrament, which anchor our moral and aesthetic imagination to Christians across time and space.

Yet TGC’s statement of faith actually includes the warning: ”…we often see the celebration of our union with Christ replaced by the age-old attractions of power and affluence, or by monastic retreats into ritual, liturgy, and sacrament.” While this may sound surprising, it’s actually the New Calvinist view that liturgy is a distracting cultural projection onto the Gospel. This is why Reformed theologian J. Todd Billings believes New Calvinists “tend to obscure the fact that the Reformed tradition has a deeply catholic heritage [and] a Christ-centered sacramental practice.”

New Calvinists prefer church in the vernacular with minimal barriers between sacred and secular, whatever that entails. This is where church can feel like a rock concert and the sermon, regardless of content, looks like a Ted Talk or whatever’s popular. Even if the theological message is solid, the cultural medium of its delivery is too important to neglect. This is why the best way to save church from negative culture is to love and appreciate positive cultural expressions of Christianity rooted in past traditions. Instead of holding loosely to your Christian subculture or denominational identity, I argue that you should dive into it.

Another problematic essay was entitled “Politics: Just Servant, Tyrannical Master” by Samuel James of Crossway Books. Like Beaumont, his claim seems uncontroversial enough: Americans should not confuse politics with God. The issue is the way James’ essay flattens political disagreement into platitudes like “No political party has a trademark on the truth claims of Jesus Christ.” Or, in explaining the dangers of excessive political engagement, he cautions “The idol of politics promises a feeling of control over this intimidating world. In reality, though, it amplifies fear by keeping our eyes off the Sovereign ruler of history.”

From James’ perspective it looks like trying to accomplish anything politically amounts to “keeping our eyes off the Sovereign ruler of history.” He probably doesn’t mean to go this far, yet the rhetoric of God’s sovereignty over history seems like an excuse for inaction or for arbitrarily chiding anyone he sees as too engaged. There is a golden mean of thinking and caring about politics; it has its proper place, but it’s a complicated debate James oversimplifies. The cliche of God not belonging to any party is also tiresome; clearly God isn’t a partisan, but that doesn’t mean we can equate Democrats or Republicans with the Chinese Communist Party or Vladimir Putin. I recently spoke with a co-parishioner who, to my horror, was enthused about Marine Le Pen, the French far-right politician. The appropriate response is not equivocation.

Fascinatingly, the theme of postmodernism and its counter to the Enlightenment’s purported monopoly on knowledge came up in close to half the essays. Postmodernism rejects appeals to universal reasoning in favor of analyzing human experience through lenses like class, race, gender and anything else related to worldview. Modernism and the Enlightenment, in contrast, argue for objective knowledge.

For example, Trevin Wax of the North American Mission Board writes in “Deconstruct Deconstruction,” that “Instead of finding… identity and purpose within the story of the Bible, [we] have adopted a faith that follows the contours of the Enlightenment’s story of the world.” Derek Rishmawy, a writer at Christianity Today, writes that “Sociologists and philosophers have been telling us for decades that we think of our lives in terms of stories, dramas, and scripts.” He references Charles Taylor, a Catholic philosopher known for his critiques of the Enlightenment.

Brett McCracken of TGC invokes language that sounds surprisingly Marxist: “[new-age spirituality] is simply a bourgeois iteration of mainstream consumerism. Capitalism loves it, because it means more products and experiences to sell to ever-hungrier consumers… To ditch religion in favor of bespoke spirituality (or no spirituality) is thus a bourgeois choice fully in keeping with comfortable consumerism.” Jeremy Linneman of Trinity Community Church uses similar language and basically makes a case for communitarianism, a philosophy critical of modernism. Ultimately Karen Swallow Prior, Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary professor, was the only essayist to explicitly defend a postmodernism, arguing that ”While this new paradigm carries risks, it also opens up the possibility for a more holistic understanding that sees reason and faith as less opposed than once thought.”

I’m not opposed to more Christian engagement with philosophers and philosophies that are considered anti-Enlightenment or postmodern. While this discussion may seem esoteric, philosophy, like history, is always political. Most who have read about critical theory or postmodernism recently have probably done so in the context of contentious debates over race and history. I recently summarized a talk with Princeton historian Allen Guelzo who stridently defended America’s Enlightenment founding against any kind of postmodernism. Guelzo blames all of the evil of the 20th century, including Jim Crow, Fascism and Communism, on anti-Enlightenment philosophy.

Guelzo’s position is probably shared by most Christians if directly asked about critical theory or postmodernism. Yet, there’s a hard-to-ignore trend among Christian writers, whether academics or pastors, invoking rhetoric that philosophically borrows from postmodern arguments. Even my own Anglican Church in North America (ACNA) catechesis a year ago began with readings from Charles Taylor and Alasdair MacIntyre, another Catholic critic of the Enlightenment. My experience with philosophy students and faculty at Wheaton College also demonstrated more interest in medieval and postmodern (or nonmodern) thought than the Enlightenment.

Christian critical discourse such as found in Before you lose your faith, on consumerism, classism and worldview is being argued in a way that looks suspiciously like a critical theory. However we rethink the relationship between religion and the postmodern, one thing seems certain: a collision is coming between defenders of modernity, especially in defense of America’s founding, and postmoderns seeking to overthrow secularism into a postsecular world. The dissonance must eventually become too hard to ignore. While an easy read for those who are newer to their Christian faith, it would have been a more compelling book if the authors had thoughtfully interrogated their own foundational beliefs.

No comments yet

Leave a Reply