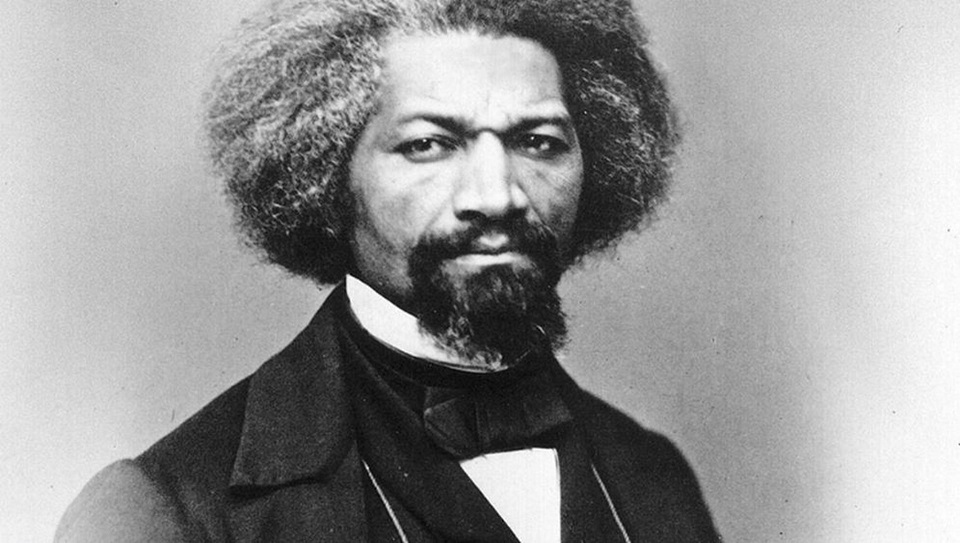

In January 1862 Frederick Douglass, former slave who became America’s greatest socio-political prophet of the nineteenth century, declared that America was facing Armageddon. “The fate of the greatest of all Modern Republics trembles in the balance.” God was in control of the nations, and America was particularly a subject of his providence.

“We are taught as with the emphasis of an earthquake,” Douglass told his listeners at Philadelphia’s National Hall, “that nations, not less than individuals, are subjects of the moral government of the universe, and that … persistent transgressions of the laws of this Divine government will certainly bring national sorrow, shame, suffering and death.”

Douglass was describing America during the Civil War. In his mind the War was God’s way of providing atonement for America’s great sin—slavery.

If white Americans repented of this great sin, the nation could experience a rebirth. “You and I know that the mission of this war is National regeneration,” he told audiences from city to city across the North in 1864. The nation would have to pass through “fire” for the new birth to begin.

The fire came of course, with the death of six hundred thousand Americans and the destruction of much of the South. But the national regeneration which Douglass sought came, if at all, only in its beginning stages. The War brought a forcible end to slavery, but lynching and segregation continued. Douglass kept reminding Americans for the next forty years that their nation was in covenant with God, and that God would hold them accountable for the ways they treated their ex-slaves and their descendants.

According to Douglass’ biographer David Blight, this idea of national covenant was central to Douglass’ long career as America’s principal prophet. “For the story in which to embed the experience of American slaves, [Douglass] reached for the Old Testament Hebrew prophets of the sixth to eight centuries B.C. … Their awesome narratives of destruction and apocalyptic renewal, exile and return, provided scriptural basis for his mission to convince Americans they must undergo the same.”

Racial relations in America have come a long way since Douglass’ time when lynching was a regular occurrence. The Civil Rights movement of the 1960s put an end to legal segregation. Affirmative action programs in government, corporations, higher education, and the media have opened access to women and minorities in unprecedented ways. Twice our nation has elected a black president.

Yet recently it has seemed that we are going backward as a nation. As Gerald Seib has put it, race remains “the great unresolved issue” in our country. “The country may have thought it had moved beyond its racial problems when the slaves were freed, when blacks were allowed to vote, when the army was integrated, when drugstore counters were desegregated, when civil rights legislation was passed or when an African-American man was elected president. But racial tensions keep recurring, like a virus that runs through the bloodstream long after you thought the disease was gone.

If Douglass were around today, he would insist that our racial dilemma cannot be understood properly without a religious perspective. Racism is sin, and one of our national sins—perhaps our greatest–has been slavery. Slavery did not begin here, and our nation’s history is filled with the quest for human rights. But Douglass was probably right. America has been sent into a kind of exile because of this massive iniquity against God’s covenant with this nation. Our continuing racial conflicts show that this exile continues. What must we do to come out of exile?

No doubt Douglass would echo Martin Luther King’s profound declaration that we should judge people not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. This implies that whites and people of color are united in their God-given humanity and can share a common character, either good or bad. It presumes that blacks and whites share the capacity to think and understand each other, if they would only make the effort.

Douglass would also point us, as he did his countrymen one hundred fifty years ago, to the national covenant. This tradition proclaims that God can forgive and heal, not only an individual but a whole society. In the Hebrew Bible God appeared to Solomon in the night and declared to him, “If my people who are called by my name humble themselves and pray and seek my face and turn from their wicked ways, then I will hear from heaven and will forgive their sin and heal their land” (2 Chron 7.14). This vision in the night from God suggests that whole societies can be forgiven and healed. It also suggests that healing depends on people turning to God in freedom and humility. This is the spiritual dimension to our nation’s division that can never be mandated by a government. There is no room for coercion here–only prayer and humility.

Our nation is hurting. In many ways it is broken. And racial division is a big part of that brokenness. But there is hope. The source of hope is spiritual, not political. It comes from humility and prayer and seeking God’s face. The God of Israel is Lord, even of this hurting land. Our racial divisions suggest that we have experienced covenantal judgment and exile. But our nation can also experience covenantal forgiveness and healing.

Gerald McDermott is the editor of Race and Covenant: Recovering the Religious Roots for American Reconciliation (Acton Books)

Comment by Mark Connolly on February 3, 2021 at 8:28 am

This is another marvellous article. Thank you, Gerald!

I have a podcast, More Christ, where I discuss the life and works of my favourite Christian writers. I had your friend, Dr Michael McClymond on and would love to speak with you. Is that something you might be interested in?

Your edited book on Race and Covenant has been most helpful, your works on Israel most fascinating, and Everyday Glory is one of my most favourite books.

Thank you and kindest regards,

Mark