Former San Francisco 49ers Player Colin Kaepernick, apparently still riding the endorphin-high triggered by his beating up on a pair of sneakers, has now gone after the whole of American independence.

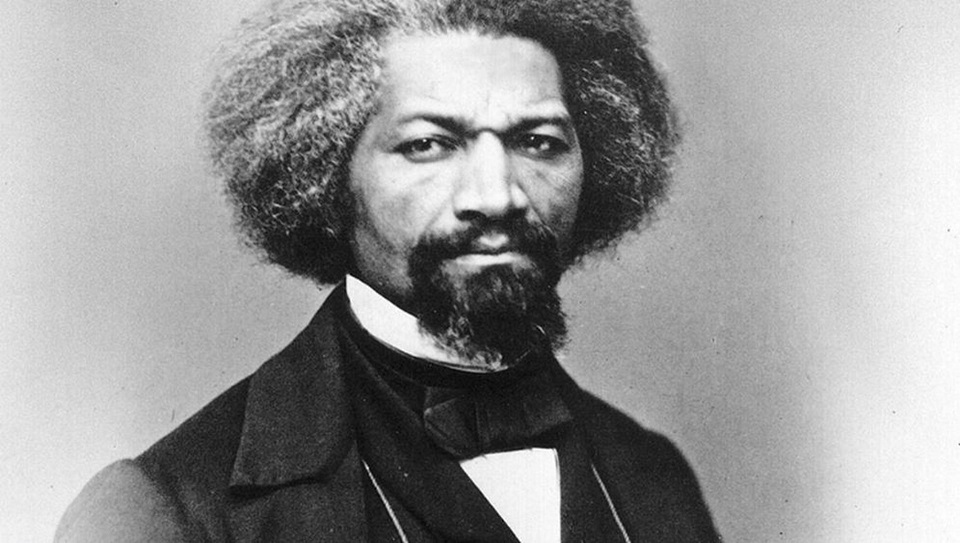

In a now-infamous tweet, Kaepernick quoted Frederick Douglass’ “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” speech, pairing it with a video showing scenes of slavery, civil-rights era abuses, and apparent police brutality against African Americans. A voice-over features the narration of James Earl Jones reading a portion of the Douglass speech. The video makes the poisonous accusation that American independence does not include black Americans. Kaerpernick posted it on the Fourth of July.

Whether or not Jones approves of the use of his reading, I don’t know—he recorded it for another context. What is apparently clear is that Kaepernick neither appreciates nor exemplifies the incredible character of Frederick Douglass.

Douglass was an American patriot who very much loved this country. Like all good lovers, Douglass hated those evils that harmed the object of his love—including not simply those evils that pose external harm to the beloved, but those evils with which the beloved is complicit. Regarding America, Douglass rightly hated the continued reality of slavery. Kaepernick recognizes this. His tweet captures this in his use of Douglass’ speech:

What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence? Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us?

The video’s narration captures even more:

I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity, and independence bequeathed by your fathers is shared by you, not by me.

These are difficult words to read on Independence Day. They cut. They shame. And they should. In Kaepernick’s hands, however, the quotations are so divorced of their context as to be misleading. Wonderfully, U.S. Senator Ted Cruz took to Twitter to help correct the record.

Douglass’ speech was delivered on July 5th, 1852. Importantly, as Cruz rightly points out, this is to say that Douglass delivered his words prior to the American Civil War. This matters.

In the antebellum period, whites throughout the country marked the Fourth in much the same way many Americans do now: family feasts, community parades, and, well, plenty of booze. Even without football, celebrations managed to impress a European visitor witnessing the festivities to proclaim the Fourth “almost the only holy-day kept in America.” But it’s true, as Kaepernik’s usage of the Douglass quote suggests, that black Americans demonstrated considerably less enthusiasm for the holiday. As CSU Fresno historians Blain Roberts and Ethan Kytle note, those blacks who did observe the holiday preferred—as Douglass himself preferred—to do so on July 5th. This served both “to accentuate the difference between the high promises of the Fourth and the realities of life for African Americans.” Not trivially, it also helped blacks in the South to avoid confrontations with drunken white revelers.

But by July 4th, 1865, the situation in the South had reversed itself. Having failed in a bloody four-year effort to defend slavery by breaking free from the United States, Confederate sympathizers were in no mood to celebrate American independence. But while southern whites “shut themselves within doors,” southern blacks embraced the Fourth with new zeal. As Roberts and Kytle write, “from Washington, D.C., to Mobile, Alabama, they gathered together to watch fireworks and listen to orators recite the Emancipation Proclamation, the Declaration of Independence, and the Thirteenth Amendment.” For the next ten years, in Charleston, celebration of the Fourth was a predominately black phenomenon:

The city’s annual celebrations commenced with a parade down Meeting Street, featuring brightly dressed citizens, politicians, brass bands, and uniformed members of the South Carolina National Guard, which, in the post-war era, was composed almost exclusively of formerly-enslaved black men. The parade ended at White Point Garden, where thousands of people would gather for a great picnic and a shady rest. The focal point of these events was a public reading of the Declaration of Independence, followed by political speeches delivered by the black Republican leaders of the day. After all the official business was over, the citizens would eat and drink, nap, frolic, and dance.

Some more revisionist views of this history want to suggest that what the black celebrants were really going on about was black emancipation, not American independence, per se. The apparent ubiquity of reading the great founding documents—such as the Declaration of Independence—disproves such speculation.

It is, of course, also true that Southern black celebrations of the Fourth did not proceed with such exuberance for long. In under a decade, after Northern occupation forces departed, bigoted whites would begin to reclaim power over their black neighbors. Brutalities against blacks during July 4th celebrations would help usher in a dark, violent, and cruel era.

Even so, the moral example of Frederick Douglass should not be lost. Kaepernick would have done well to read Douglass’ entire July 4th Speech. He might have been surprised to see that Douglass uses the phrase “fellow-citizen” no less than twelve times, this to an audience made up mostly of whites. Douglass spends the first half of his talk reminding these fellow-citizens of their shared history—emancipation from the tyranny of England, the great American men who rose up to create a great America, their willingness to forgo a life of ease and, instead, to pursuit justice, life, liberty, and human flourishing. Douglass does not deny any of this.

Indeed, he uses it to demonstrate his sorrow for having to make the denunciations that lie ahead. Moreover, he takes this great national history and grounds his own personal history within it. Noting the privilege of addressing the assembly he says:

The distance between this platform and the slave plantation, from which I escaped, is considerable — and the difficulties to be overcome in getting from the latter to the former, are by no means slight. That I am here to-day is, to me, a matter of astonishment as well as of gratitude.

It is only then that Douglass embarks upon his damning assault against slavery. His rhetoric is far more incandescent than anything that could ever be conveyed via Twitter. He is astonishingly brilliant in his condemnation. And yet, through it all, his tactic is to remind America that when it comes to slavery America has betrayed herself. Douglass deploys American virtue to attack American sin. His venom is what love looks like on the assault. Because of everything he has said about the greatness of America, his end-game is clear: he means to rescue America. He means to return to her the full measure of her goodness.

Unlike Kaepernick, moreover, Douglass does not lose faith in America: “Allow me,” he writes, “to say, in conclusion, I do not despair of this country.”

Allow me to say, in conclusion, notwithstanding the dark picture I have this day presented of the state of the nation, I do not despair of this country … There are forces in operation, which must inevitably, work the downfall of slavery … the doom of slavery is certain … I, therefore, leave off where I began, with hope.

Douglass, happily, would live to see an America that made good on his faith in her righteous spirit. In fact, by calling his fellow black Americans to enlist with the Union in the Civil War, it was a task in which he encouraged his brothers to take part. As President Trump said in his own July 4th speech:

Devotion to our founding ideals led American patriots to abolish the evil of slavery, secure Civil rights and expand the blessings of liberty to all Americans …This is the noble purpose that inspired Abraham Lincoln to rededicate our nation to a new birth of freedom, and to resolve that we will always have a government of, by, and for the people.

Kaepernick—and those who cheer him on—do not stand in the tradition of Frederick Douglass. In their eagerness to scold, their apparent refusal to accurately describe the reality around them serves only to divide, not too unite. They are a part of the problem, not the solution.

Christians must follow Douglass’ example. We should not shy away from denouncing evil where we find it. But we must not shy away from acclaiming goodness either. When both are found in the same person, or movement, or nation, or any other entity—who should lay aside the easy task of polemical hyperbole and carefully trod the harder path of speaking truth in love.

Marc LiVecche is the editor at large for Providence, and the McDonald Visiting Scholar at the McDonald Centre for Theology, Ethics, and Public Life at Christ Church, Oxford.

Comment by David on July 6, 2019 at 8:17 am

Slavery in the UK was abolished in 1833/4. Pennsylvania passed a gradual abolition of slavery in 1780 that seems to have eliminated slavery by 1847. Whether a slave benefited from American independence depended on where they lived. Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclaimation only freed slaves in the Confederacy where he had no authority. Slaves in Maryland and Delaware, both Union territories, had to wait. Some also claim that Native Americans would have benefited from British rule. So July 4th is a mixed bag.

Comment by td on July 9, 2019 at 9:21 pm

July 4th is not a mixed bag for me; i am an American and proud of it, and i am proud of our nation’s great history.

Have we done some things wrong? Sure thing. But to decide that the whole thing is rotten because we haven’t always lived up to our ideals is cynicism and pessimism at its worst. My heart aches for those who find nothing worth celebrating about our country.

Comment by Dan W on July 6, 2019 at 3:04 pm

Excellent article Marc! July 4th 1776 wasn’t the day the 13 colonies became independent. It was the day the Continental Congress approved the final wording of the Declaration of Independence https://tinyurl.com/og4lrfm . You could say we celebrate the ideas enshrined in the Declaration on July 4th.

Comment by dewey boyd on July 6, 2019 at 3:34 pm

Why Should African Descendants Of Slaves Celebrate America’s Independence Day ?

I am in support of Colin & Fredrick Douglas

Comment by td on July 8, 2019 at 6:00 pm

If perfection is the standard that has to be met to celebrate our nation’s founding, then no one should celebrate it. Let’s just give up this whole democracy experiment thing. Have people in our country sinned? Have people in our country excelled? Do we have ideals in common that we can celebrate collectively?

I can’t give you a reason to personally celebrate it, and no one is forcing you to.

Comment by Search4Truth on September 1, 2019 at 2:09 pm

It’s hard to keep a straight face. You are for up and down at the same instant?