“The scandal of the evangelical mind is that there is not much of an evangelical mind.”

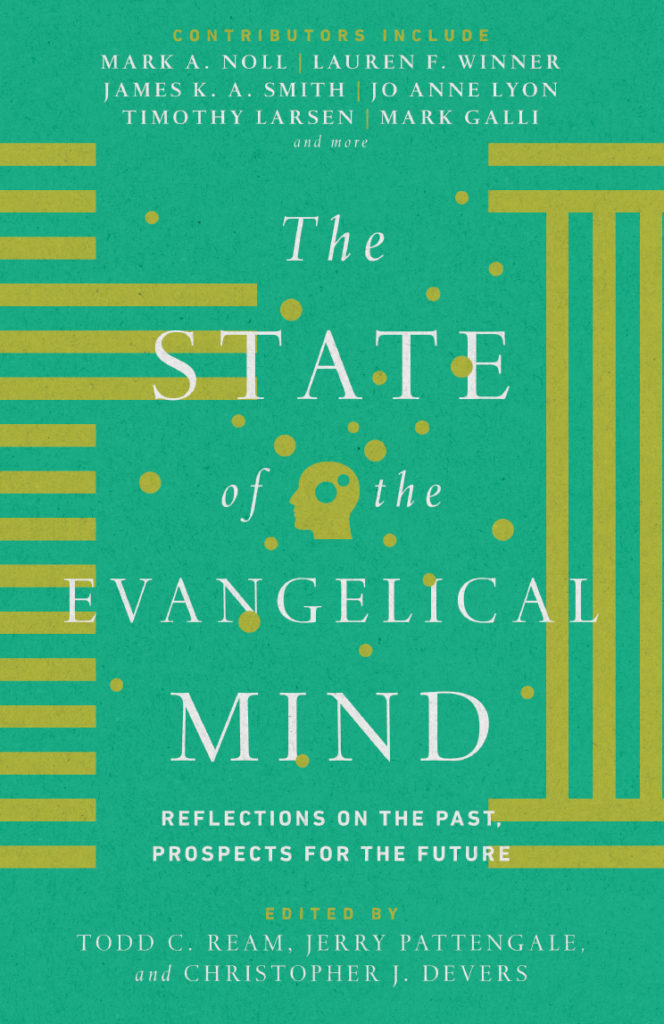

With that scathing notion, Mark Noll kicked off his 1994 book, The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind, which aggressively critiqued evangelicals’ lack of intellectual scholarship. This year, he published a sequel, The State of the Evangelical Mind to determine whether anything has changed. The new book features a collection of essays, with different writers for every chapter.

This latest evaluation of the evangelical mind was mixed. Noll himself quipped, “In a word, it is the best of times, and it is the worst of times.” Some of the authors seemed even to disagree about what the term “evangelical mind” means.

Sometimes, they meant the intellectual contributions that evangelical scholars have made in the larger academic community. Many of these contributions, especially in the sciences, would naturally be non-sectarian. The book generally affirmed that evangelical scholars have individually made progress over the last 24 years, although their institutions often struggle to keep doors open.

In contradiction, sometimes they meant the intellectual contributions unique to the particulars of evangelicalism. This interpretation seemed odd, as some marks of evangelicalism (the book mentioned revivalism and pietism, in particular) are inherently emotional, not intellectual. Other marks of evangelicalism, such the emphasis on Scripture or the Gospel, will likely be treated as folly by non-Christians (1 Corinthians 1:18).

The book mentioned some other problems evangelicals face. Much evangelical energy which could have advanced intellectual projects has tied itself up in partisan politics. Additionally, like the rest of society, they fear evangelicals are being dumbed down through social media, extremist ideologies, racial antagonism, and “artificial tenderness” in universities. Such broad, sweeping claims cannot possibly describe every corner of evangelicalism, but may accurately summarize a large portion of it.

Due, I think, to miscommunication among the various authors, the book neglected to address some important topics. Four of the book’s six chapters were supposed to analyze evangelical progress in specific institutions. Chapter 2 (churches) summarized the ongoing activism of parachurch organizations. Chapter 3 (parachurch organizations) showed how such organizations are still alive and well on university campuses, and are one way that people blend evangelicalism and the life of the mind. That chapter also featured a second author, who mainly critiqued Noll’s 1994 book. Chapter 4 (colleges and universities) expertly defended the need for Christian colleges to offer a classical liberal education in the 21st Century, but failed to mention evangelicals. Chapter 5 (seminaries) explained the role seminaries ought to play without saying evangelical seminaries are doing so. Having read the book, I’m confident that evangelical parachurch organizations are still as strong as ever, but I’m unclear on whether the authors think evangelical churches, colleges, universities, and seminaries are contributing to the life of the mind.

I was disappointed that the book’s authors missed an opportunity to highlight the neo-Reformed movement among evangelical churches that is attempting to reclaim an intellectually rigorous, Reformation-era Protestantism. Churches in this vein feature long, expository sermons after the style of Jonathan Edwards and other Puritan ministers. The elders model serious, theologically grounded prayers and personal intellectual engagement with Scripture. They sing hymns that drip doctrine like honey from a comb—both old (by Isaac Watts, Charles Wesley, even some from the 7th Century) and new (by Sovereign Grace Music, Keith and Kristin Getty). In a 2004 article, Mr. Noll renewed his call for “intellectual seriousness, intellectual integrity, and intellectual gravity” among evangelicals, and I believe such churches fit the bill—both in terms of worship and in the professional lives of their laity.

Perhaps Mark Galli (one of the only evangelical contributors) had such churches in mind in the concluding chapter when he defended the intellectual capacity of evangelicals. For example, Galli defended the “inductive Bible study” technique taught in these churches. For those who may be unfamiliar, the inductive Bible study method encourages Christians to approach every passage of Scripture by 1) observing what the passage says, 2) interpreting what it means, and 3) applying it to their lives. It formalizes the emphasis on personal Bible reading that was a major theme of the Protestant Reformation. Noll discounted inductive Bible study in his 1994 book because he said it was too similar to scientific empiricism, but Galli pointed out that it trains a church’s laity to engage with the biblical text at a level that even a secular graduate school professor would call “impressive.” Even while he defended the intellectual capacity of some evangelicals, Galli also acknowledged that it often looked more generically Christian or Protestant, without any particular distinctives of evangelicalism.

Given the lingering criticism of evangelicals, it’s fair to ask what sort of evangelical life of the mind would satisfy these scholars. They seem wistful for a broad cultural influence that mainline Protestantism enjoyed in the mid-20th Century, with public intellectuals such as Reinhold Niebuhr. But as mainline Protestants influenced the secular culture, the culture influenced mainline Protestants. Today, it’s hard to tell the difference—and it seems like many mainline Protestants are now taking their cues from the secular culture. Their lack of distinctiveness has contributed to the decline of many mainline Protestant denominations, even while evangelical members hold steady. If evangelical churches are supposed to follow the model of mainline Protestants to influence the culture, what will prevent them from suffering the same reverse influence and then declining membership?

Over the past 25 quarter century, evangelicals have made some progress in undoing the instinct to anti-intellectualism. The challenge moving forward will be in how to cultivate a distinctively Christian life of the mind that can engage the world with the message of the cross without succumbing to its foolish, fickle fads.

Editor’s note: The original version of this article erroneously attributed the contributions of Mark Galli to James K. A. Smith.

Comment by Ric on January 12, 2019 at 5:36 pm

Mr Arnold,

Could you please clarify your comment that Mark Galli is “one of the only evangelical contributors”? I’m not clear whether this means the only contributors were evangelical or that that few of them are. If the latter, please explain why you came to that conclusion. I’m genuinely puzzled.