Broad American support for international religious freedom as an ideal and goal of American foreign policy against often violent persecution continues to exist, but presenting religious freedom as an ideal is complicated by the domestic controversy concerning liberty of conscience. This was clear at a panel discussion of “Tolerance: a Key to Religious Freedom,” presented by the Religious News Foundation/Religion News Service. The discussion was hosted by Thomas Gallagher, CEO of the Religious News Foundation, and moderated by Thomas J. Reese, Chairman of the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom. Panelists included former U.S. Representative Frank Wolf, Rabbi David Saperstein, former Ambassador-at-Large for International Religious Freedom, Dr. John Sexton, President Emeritus of New York University, and Joyce Dubensky, Esq., CEO of the Tanenbaum for Interreligious Understanding.

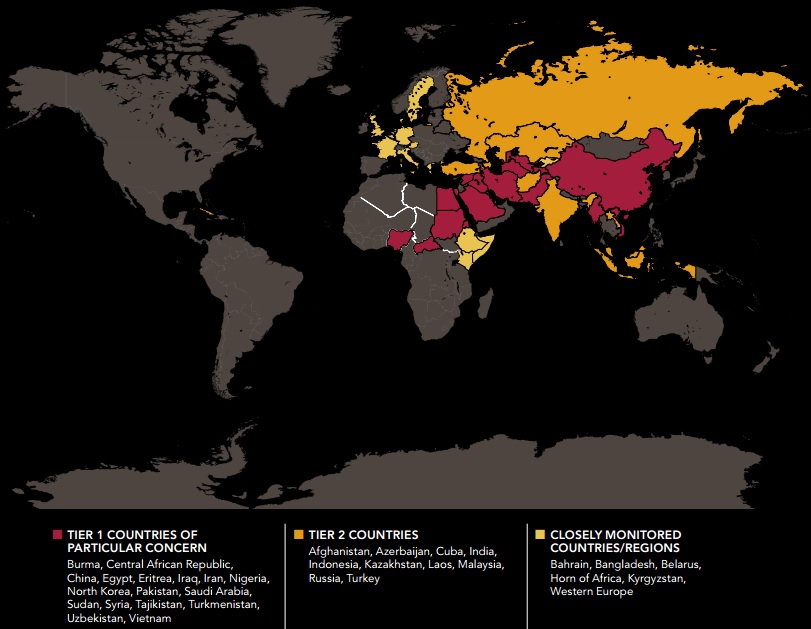

Reese gave numerous examples of the denial of religious freedom in the contemporary world, such as ISIS’ savage attack on religious minorities in Iraq and Syria, Pakistan’s blasphemy laws, and Russia and other post-Soviet states’ favoritism to familiar and preferred religions as against government treatment of other religious groups with suspicion. In general there are two motivations for religious persecution, Reese said. First, disfavored religions are deemed to threaten state power or a state ideology. North Korean repression of all religious activity, the persecution of Rohingya Muslims in Burma, the Chinese government deeming house churches to be desperate cults, and its attack on Tibetan Buddhists and Fulan Gong are examples of this first kind of motivation. Secondly, there are religious states that persecute religious dissidents, adherents of other religions, and unbelievers based on the state’s theology. Iran and Saudi Arabia fall into the second category.

Former Congressman Wolf expressed appreciation to Rabbi Saperstein for his efforts in having the designation of “genocide” applied to Christians and other religious minorities in Iraq. In reviewing the many religious freedom hot spots in the world, Wolf noted that China is an “equal opportunity persecutor,” persecuting, among others, Uighurs and Tibetan Buddhists. The disinterest of the world in the plight of the Uighurs has led to their radicalization, Wolf said, while Tibetan Buddhists monks have burned themselves alive “because no one is advocating for them.” In China itself, 900 churches have recently been “burned or destroyed.” Wolf called the Boko Haram based in Nigeria the “most dangerous terrorists group in the world.” The breakup of Nigeria, which is now possible because of Boko Haram’s terrorism, is an “existential threat to Europe,” as it will result in many more refugees. He said that the world “missed genocide” in Rwanda and Srebrenica, as well as Iraq, where the Christian population has been reduced by death and emigration from 1.5 million to 250,000. “We are seeing the end of Christianity in the cradle of Christendom,” Wolf said. In the Iraqi conflict, 3,900 Yazidi women are reportedly still held by ISIS. We need to follow past practice, Wolf said, of going to foreign countries where religious freedom is denied, as was done with the Soviet Union in the past, with lists of prisoners, and press for the humane treatment in prison and release. By publicizing to the wider world of prisoners of conscience, their situation improves. Testimonies of former political prisoners confirm this to be effective. Wolf said that we should “restore the covenant” for the persecuted.

While of far less magnitude, America is not immune from religious violence, Wolf said, as Jewish students on American college campuses are targeted for violence. He emphasized support for international religious freedom is and must be bipartisan, supported both by conservative Republicans and liberal Democrats. Both Former Democratic Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi and conservative Republican Representative Chris Smith agree on international religious freedom, he said.

Dubensky said we need to consider what real freedom means for people in everyday life. Religious freedom means the right to believe or not, to be able to share those beliefs or not. It would seem obvious, however, that what religious freedom must also mean in real life is more than this. If state accommodation of religious commitments is serious, there is also the right to act on religious beliefs. Dubensky continued by saying that supporting religious freedom means we must “combat religious prejudice and violence.” Societies should be “safe for religious difference.” Children are bullied in schools for reasons connected with religious freedom, she maintained, and working with teachers will help, training them in skills and providing education concerning religious freedom. A misconception, she said, is that teachers think they cannot talk about religion. She concluded that “religious freedom is a very big idea.”

Sexton observed how broken the world is and how much there is to be done. But he recommended that despite this, we should maintain an idealism about what can be done, in the “spirit of Don Quixote.” The world should live as a “community of communities.” Individual communities should consider “how the world sees us.” He maintained that law is the “sacred religion of America.” He believes that in the contemporary American situation, religious and secular dogmatism are in a feedback loop, one reinforcing another. There should be a “healthy disrespect for authority.” If we take the “long view,” he believes that we will see “the core problem” is “the mindset of certitude and triumphalism.” This mindset can be secular or religious.

There seemed to be an implicit universalism in what both Dubensky and Sexton said. They tended to indicate that the idea of religious freedom is part of a larger universalist theology, in which all religious roads lead to God. If American law is now acting as a kind of state religion in the conflict over liberty of conscience, it is secular dogmatism that is the driving force, insisting that the inclusive values of the state override the religious conscience. The only “dogmatism” of traditional religious believers is their insistence that they be free to live their lives according to their own religious precepts, regardless of who is offended. They are not requiring that others believe or live as they do.

Saperstein praised Frank Wolf as having made a tremendous difference for international religious freedom. Saperstein believes that religious freedom can be either a doctrine of “tolerance” or “pluralism.” There are “tolerable deviations” and “intolerable deviations” from commonly accepted ideas and values. Toleration presumes a disagreement. We tolerate what we think may be wrong. While he seemed clear that there should be freedom for exclusivist religions, Saperstein said that in stating that Jews are acceptable to God without accepting Jesus as the Messiah, as it recently did, the Vatican has moved from toleration (mandated by earlier church pronouncements) to pluralism.

There is a problem with religious freedom if there are limits in religious belief and practice “beyond which people won’t go.” In the American understanding of religious freedom, the government can override religious freedom only for a compelling state interest, exercised in the least restrictive way. In many other countries, Saperstein said, there is a lower standard of religious freedom, in which religious freedom is granted, but it must not offend the prevailing doctrines in society. This is simply toleration, not freedom. (This observation certainly invites the conclusion that this lower standard of religious freedom is what is being applied to bakers and florists in this country when they decline involvement in homosexual behavior).

Saperstein said that an important insight in western religious freedom is the understanding that the government cannot give or take away fundamental rights. This, he said, is a “revolutionary notion.” But again, it appears that taking away fundamental rights is what is happening in the baker and florist liberty of conscience cases. Fundamental rights are indispensable to a free market of ideas, Saperstein maintained. This inalienable freedom, or pluralism, is again, different than toleration. He said that exceptions taken by national governments to the international religious freedom provisions of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCR) lead to “overbroad” interpretations that substantially deny religious freedom by some countries. He pointed out that James Madison believed that people should enjoy the fullest tolerance based on conscience. Dictates of conscience are important, he maintained (as this writer has argued repeatedly, the right of conscientious objection, or declining actions understood to be evil, should be absolute).

In a question and answer session, Reese asked Wolf “what can the U.S. do to influence China for religious freedom?” Wolf said that we must “alter our behavior.” The President should speak out on international religious freedom here. President Reagan spoke for international religious freedom at the Danilov Monastery to Mikhail Gorbachev. Reagan told the Russians to tear down the Berlin wall. Wolf again said that the President and diplomats should go to problem countries with a list of persecuted people.

Reese then asked “What can corporations do to lobby for religious freedom in China?” Dubensky said businesses are in business to do business. A lot of companies have learned that when religious freedom is respected, it is good for business. Multinational corporations have influence greater than that of many small countries, she said. These companies should be rewarded with good talent due to their support for international religious freedom.

Sexton said that we should develop critical thinking to advance international religious freedom. Half of students in China had a hard time understanding what religious freedom is. Education about religious freedom is therefore important, he said.

Reese asked, “What is the good news?” Saperstein pointed to two things: 1) Work with prisoners of conscience, which encourages them; and 2) Congress has substantially increased programmatic activities. These efforts have done such things as getting Vietnam to move from an approval system to a notification system in the assignment of priests, so that the government need not be involved in internal church affairs. We need to address as well the situation of people who are second class citizens simply because of their religious beliefs, he said.

Wolf said that in developing good religious freedom policy “personnel is policy,” i.e., it matters to good policy who is in a decision making capacity. Also, “politics is downstream from culture,” so that the public must have a good understanding of religious freedom for strong religious freedom policy. Travel is important, Wolf said. Nothing changes minds and brings commitment more than actually going to areas where there is religious persecution and seeing the people and situations involved – this was true for him, and was also true for others. Travel is not a “junket to Paris,” but to places like Nigeria, Wolf said.

A questioner asked if the issue of the legal consequences of the sexual revolution versus religious freedom should be raised to the level of a government religious freedom concern. Dubensky said that core beliefs are in conflict; the question is how we can accommodate both adherents of traditional religious sexual morality and those committed to other understandings of sexual morality. She gave as an example a Catholic hospital with Jewish woman for whom abortion is recommended in an emergency situation. The questioner responded that people from other countries are saying that the domestic religious freedom conflict in America makes it difficult for Americans to press for international religious freedom in other countries. If America ceases to be an example for religious freedom, how can other countries look to America to see what religious freedom should be?

Saperstein said that there is very liberal and very conservative support for international religious freedom in American politics. Can domestic religious freedom be the same? He said he takes very seriously the claims of traditional Christians and other traditional religious believers not to be complicit in what they consider to be immoral, while at the same time taking very seriously the claims of LGBT identifying persons not to be treated as disfavored minorities were in the past. Saperstein said that violent persecution in other countries is much worse than the current Western conflict of conscience over the sexual revolution.

This openness to the claims of conscience is encouraging, but as this writer has noted in the past, the claims of conscience should prevail, because it is clearly the party of whom action is required who is being imposed on in a moral conflict, and declining service is based on religious objections to the service requested, not the identity of the customer.

The issue of liberty of conscience against the sexual revolution appeared in this presentation, as in others, as a nagging problem at the heart of an otherwise broad consensus in favor of religious freedom across the American political spectrum. Colonial America was founded in no small measure by people seeking the freedom to live according to their religious consciences, and is thus a large part of the basis for American civilization. Similarly the American founders made religious freedom the first freedom of the First Amendment of the Constitution, and since it is concerned with what is ultimately right and wrong, it is very reasonably the freedom that informs all others. If it turns out that the consciences of millions of traditional religious believers in America are an “intolerable deviation” from a prescribed American way of life, then American commitment to religious freedom will be severely restricted, and the meaning of America, both for itself and for the world, as a land of the free will become a hypocritical ideal, destroyed by the “certitude and triumphalism” of the sexual revolution. Only if America continues to hold the religious conscience to be of primary importance can the country consistently advance the ideal of religious freedom in the world.

Comment by Joseph O'Neill on February 26, 2017 at 12:59 am

US pays apartheid Israeli regime $3.8 billion [per year to kill Chritian and Muslim Palestinians.