“In Washington, I was to confront a foreign policy establishment dominated by hardliners who had viewed the Soviet Union as an implacable foe for decades, as well as some who saw a political upside in heightened tensions. My interest in and study of Russian culture, art, and the religion of the Russian people made me not only an unusual voice, but, indeed a unique one in the foreign policy establishment. Their opinions often contrasted diametrically with mine. I found the accepted orthodoxy about the Soviet Union limiting and in many instances just plain wrong. My position was always clearly very different and not popular in the official circles of both nations; I was anti Soviet regime but pro Russian people.”

—Suzanne Massie, prologue to Trust But Verify: Reagan, Russia and Me (p. 18)

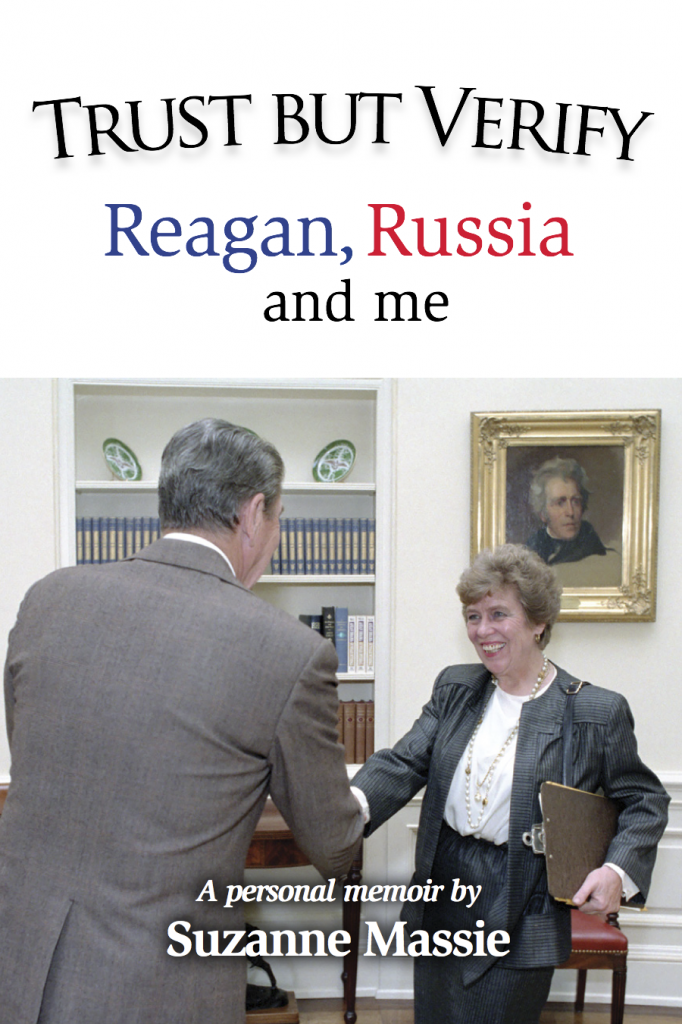

Suzanne Massie never imagined that she would one day come to play a crucial role in the end of the Cold War, nor that Ronald Reagan would praise her in his diary as “the greatest student I know of the Russian people.” By the time she first sat down with President Reagan in January 1984, the best-selling author and historian had established herself as a leading authority in the field of Russian cultural history. Still, as she writes in the prologue of her gripping memoir Trust But Verify: Reagan, Russia and Me (Maine Authors Publishing), she was far from a conventional choice to advise the President at the height of tensions between the regime Reagan had recently condemned as the “evil empire” and the United States:

“I was not a traditional PhD-carrying academic, and my views were far from the establishment view of the time. This was the result of what had happened to me over several years in the frigid Cold War period of little or no close contact between Americans and ordinary Russians. I had traveled often to the Soviet Union and had been lucky enough to get to know a wide variety of Russian people in their own environment, to share their conditions of life, learn about their problems. I was deeply touched by them and what I had experienced. I learned firsthand how Soviet propaganda and our isolation from their long-suffering people had blinded us to the harsh reality of their lives. In fact, it is not too much to say that we in the United States had swallowed Soviet propaganda more completely than the Russians themselves.” (17).

It was Massie’s conviction—born from her lifelong love of Russian culture and her life-changing encounters with ordinary Russians living behind the Iron Curtain—that there existed a crucial distinction between the official mask of the Soviet regime, and the reality of life as lived by the Russian people, that impelled her to action. “From personal experience”, she writes, “I had learned how much Russians hated being referred to as a synonym for a regime that most felt had been imposed on them by force. Russian citizens regularly referred to their government as them and themselves as we.” (18).

At the time she began meeting with Reagan, Massie’s understanding of this critical distinction was completely foreign to senior administration officials, and, as a result, absent from U.S. foreign policy toward the Soviet Union. Worse than that, Massie came away from her first meeting with the President and his advisers incredulous that no one had evidently informed him about the crucial role the Orthodox Church had played in the formation of Russian national identity and continued to play in Russian life despite its ongoing persecution. While she understood from her studies and travels to Russia that the Church was “inextricable from Russian history, and lies at the core of Russian identity” (135), Reagan had been unaware that it had even managed to survive:

The one thing that startled me most about my first meeting with President Reagan was that the President of the United States did not know how important religion had been—and still was—to the Russians, or even it seems, that the Orthodox Church in Russia continued to exist. Evidently no one had ever told him. But how could this be, with the army of experts and specialists available to him in Washington?

The moment impressed me so strongly, especially because when I met him in 1984, despite all the persecutions of their faith, some 55 million Russians were ready to state that they were Orthodox, more than three times the members of the Communist Party, which then numbered 18 million. This made Brazil, the United States, and the Soviet Union the three largest Christian countries in the world.

For me, this gap in the President’s knowledge was striking because, of all the developments I witnessed between 1967 and 1991 announcing the end of the communist regime in the Soviet Union, none was more significant in that officially atheistic nation than the clear signs of a renewed search for faith and morality and the steady return of Russians to the Orthodox faith of their ancestors. Yet despite mountains of information and intelligence reports, nothing was more ignored, or, if noticed at all, dismissed by our Soviet specialists.” (134).

Reflecting on her first Oval Office meeting with the President—in which she faced not only Reagan, but a host of intimidating, exclusively male senior officials staring at her expectantly—Massie was shocked to realize that no one at the highest levels of power in Washington had understood the significance of these two factors. She understood that no progress could be made in Soviet-American relations without the President coming to understand the distinction, in human terms, between the indomitable Russian people and the Soviet regime which terrorized them, as well as the perseverance of the Orthodox Church despite seven decades of brutal repression. Fortunately for Massie, and the cause of world peace, she had a star pupil, as Reagan instinctively understood that, where the godless communist regime was concerned, “religion might very well turn out to be their Achilles’ heel.” (135).

It seems almost unthinkable today that senior administration officials had no understanding of these things. While they certainly viewed the Soviet Union as a tyrannical regime, how could they not have bothered to see the disconnect between the communist rulers’ propaganda and the actual perceptions of the ruled, or understood that the Church, as “the only non-Marxist-Leninist organization to exist at all” (138) in the USSR, represented for Russians not only their spiritual patrimony, but their last living link with their own history prior to the Revolution?

The only possible answer is that, until Reagan, our leaders simply were not bothering to try to really understand Russians, their history, or their culture. In Trust but Verify, Massie offers incisive insight into how many U.S. diplomats, rather than seeing the Orthodox Church in strategic terms as the ultimate enemy of communism, instead dismissed it as hopelessly compromised, infiltrated, and irrelevant. “Throughout the Cold War”, she writes, “the common refrain in the United States establishment was that Orthodoxy was a dead religion in the Soviet Union, a dusty relic of the tsarist regime, and that the majority of the population was not interested.” (139). Yet Massie understood something no one else did at the time, that a significant factor behind this disconnect was the complete unfamiliarity of Americans, on a cultural level, with the notion of a nation being founded on one religion:

“There were reasons for our official blindness, among them that in the United States we have the tendency to see everything as a reflection of our own beliefs. Being “like us” is equivalent to being “right.” We in America can choose our religion as if we were shopping for a new car, changing at will, and harbor thousands of offshoots and sects. Because our history is founded on personal choice for all religions we have no experience or understanding of a religion that represents a nation, and we find this somehow disturbing. The history of Russia is the opposite, and the communist regime of the Soviet Union always understood this fact completely.” (135).

Massie offers profound insight into another reason why the U.S. political and intellectual establishment failed to understand the crucial importance of the Orthodox Church in Russian history and national life. Because American political culture reflected “the ironbound principle of separation of church and state”, U.S. policy-making consequently took place in a completely secular atmosphere, with the result that

“the effect of God and religion was banished from serious discussion of policy or relations between nations. Indeed, so secularized did our policy makers and media become that it was almost considered a mark of naivete, lower class, or right wing [ignorance] to mention religion at all. I believe this to be one of the most important reasons that we completely missed the political importance of the Catholic revival in Poland when it began and the role of Orthodoxy in the fall of communism in the Soviet Union, as well as the fundamentalist movement in Iran. As it has throughout human history, religion remains one of the strongest forces in the world. . .” (139).

It seems extraordinary that so many of our brightest officials were somehow unaware that, in that beleaguered institution, the Orthodox Church, lay the seeds of Russians’ resilience, and their post-Soviet identity and cultural reawakening. Given the complete absence of such insight from within his inner circle, it was Massie’s unique awareness of the Church’s crucial importance to Russian history and culture that made her an invaluable adviser to Reagan.

Writing of the extraordinary disconnect between the Soviet propaganda and the reality of life for ordinary Russians, Massie notes that, far from any kind of socialist paradise, “communist law had declared that each citizen was entitled to only nine square meters (eight and a half by ten feet) of living space”, with the result that “whole families often lived in one room and used a communal kitchen” while “people were routinely called in for interrogations. . . [or] thrown into psychiatric hospitals for a harrowing weekend or longer.” (29).

Yet, despite the atmosphere of constant uncertainty and fear of repression, she also discovered Russians’ profound “humor, generosity, ingenuity, and courage.” (29). Refusing to be told what they could or could not listen to, or how or when they could dance, Massie took note of the significance carried by even seemingly small acts of rebellion: “People would go far into the countryside for a chance to hear the Voice of America, and once, in a distant park, we danced to Duke Ellington’s music.” (30).

Unbeknownst to her at the time, Massie first came to the White House when relations between the two superpowers were at their lowest point during the Cold War. During President Reagan’s first term, she writes, he was “a fervent anticommunist surrounded by hard-liners” (17), and, with poor communication on both sides, the world came perilously close to the precipice of nuclear holocaust. By December 1983, in the wake of a massive U.S. military buildup and the Soviets’ shooting down of a Korean airliner with Americans aboard, the Soviets had broken off all arms negotiations.

It was into this unenviable climate of an all-time high in tensions that Massie entered as a complete newcomer, “a virtually unknown person who had never served in government” (19). Against all expectations, most of all her own, she set out to share with the President what she knew of the Russian people, and, in the course of sixteen extraordinary meetings, she offered a perspective unlike any of his other advisers. Communicating much-needed insight on the values, outlook, and dreams of the Russian people whom she had come to love so deeply, Massie believed that Reagan would also come to love them, if only he could come to know them apart from their hated regime.

Part II of my review for Suzanne Massie’s memoir Trust But Verify will be published here on Monday, December 2.

Comment by Deborah Herz on February 8, 2014 at 6:53 pm

Hi Ryan,

Thank you so much for posting your interview with Ms. Massie. I plan to interview her in the next week and wonder if you might be able to share some of your most impressionable moments with her … Quotes, anecdotes, and your experience working on this story with her. She is a national treasure.

Thank you and best wishes,

Deborah Herz

Managing Editor

Salve Regina University

Comment by Ryan Hunter on September 13, 2014 at 6:02 pm

Hi Ms. Herz,

Thank you very much for your message. Unfortunately, I only came across it now. I hope your interview with Ms. Massie went well! She’s a delightful woman, and a treasure-trove of information on Russian cultural history.

With best wishes,

-Ryan