Discussion at last evening’s Moving Faith Communities to Fruitful Conversations about Race panel at Wesley Theological Seminary in Washington, D.C. wavered between practical solutions to certain effects of racism to vague calls for guilt, discomfort, and conversation. At a panel made up primarily of United Methodist church leaders and journalists, the US attorney for the District of Columbia, Ronald Machen Jr., stood out as the only participant to present clearly defined problems and solutions.

Machen discussed the distrust and fear of law enforcement that is often in place in African American communities – emotions that, given the Justice Departments exposé of racism in Ferguson, are often justified. This is, for Machen, a problem because without relationships with law enforcement, people do not get involved with crime prevention. Without trust that law enforcement is there for their good rather than merely to lock people up, people do not come forward as witnesses to crimes. Machen’s solution – a solution he and his office are putting into practice – is to create relationships between law enforcement and communities.

A large component of that solution is a clergy ambassador program where law enforcement maintains relationships with clergy in the community who then help build trust for law enforcement within their congregants. These clergy can then also be a voice from the community to law enforcement when the community feels that something is amiss. Other aspects of the solution are to involve law enforcement in crime intervention and prevention programs, again with the intention of creating relationships. Also important is developing community policing models where neighborhoods are patrolled by officers who live in those neighborhoods. Machen went on to assert that these efforts were working, that incarceration rates were down. He expressed his hope that the success of such programs would be the best way to win over the opposition; this conversion through demonstrable success was the method championed by Booker T. Washington.

Machen had to leave the panel early, and was replaced by Principal Assistant U.S. Attorney Vincent H. Cohen, Jr. who continued the discussion of practical solutions. Cohen asserted that there is no major change in the US without the participation of the faith-based community. Because all citizens make up the jury pool and the pool of potential witnesses, it is important for law enforcement to develop relationships with churches and, through them, their communities. He highlighted the need to educate clergy about clergy privilege, elder and domestic abuse recognition, and how to teach their congregants to be courageous in addressing injustice. Cohen concluded by imploring churches to urge cooperation with law enforcement in testifying against criminal defendants, citing a recent murder on a basketball court whose 20 witnesses refused to testify.

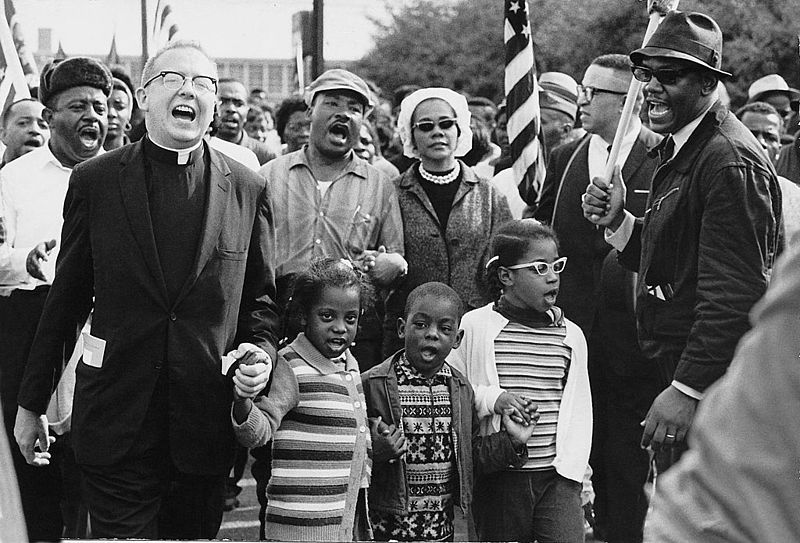

The rest of the conversation remained in the abstract. While several of the panelists noted that churches and clergy were often at the forefront of civil rights agitation, nearly all of them castigated churches for not doing enough in the present to address the alleged racial divide. Michel Martin, a journalist, recognized that polling shows people think race relations have gotten worse in recent years, but argued that “disquiet” and “being uncomfortable” is not failure because it can lead to “conversation.”

“Conversation” seemed to be the primary desire of most of the panel. Krista Tippett, another journalist, argued that churches and seminaries need to create spaces for conversation rather than remaining dependent on politicians or the media for that space. The Rev. Dr. Joseph W. Daniels Jr., a district superintendent for the United Methodist Church, expressed his disappointment that neither his denomination nor his bishops had an official statement on race; presumably, the words of Scripture are not enough. The Rev. Rachel Cornwell, Lead Pastor at Silver Spring United Methodist Church, expressed fear that, being a very diverse congregation, her church would feel safe and affirmed rather than uncomfortable and challenged. The Rev. Tom Berlin, Senior Pastor of Floris United Methodist Church spoke about the connection between hiring a Pakistani pastor and getting South Asian attendees to volunteer for the preschool.

Throughout the conversation, the assertion was made that if the church wanted to remain relevant – in an age of millennials and decreasing white majorities – it must become more diverse and focus on diversity conversations. Yet the proposed solutions were vague at best. When asked what concrete steps the seminary could take, panelists responded with “build a biblical worldview into students and community,” “help people to be courageously faithful,” “create risk-takers,” “notice who is missing from the conversation who should be there,” “pray and move your feet,” and hold seminary classes out in community buildings and on the street.

Unhelpful to the progress of the discussion was the lack of definitions. None of the panelists defined the race problem as they saw it, nor did they discuss what racial harmony would look like. Missing those crucial elements of problem solving, it is unsurprising that their calls to action remained abstract. Also cloudy was their understanding of the nature of the church. Does the church exist as an instrument of socio-political change? Or is the church intended for the administering the means of grace and for the pastoring of souls? Does the parish model – one centered on particular places – fail to meet the mission of the Gospel? Is there ever an end to the “conversations” about race that ought to be happening in our churches, or are we condemned by the Gospel to being challenged and uncomfortable? Without a clear understanding and diagnosis of the problem and a clearly delineated solution, these questions can never be addressed.

Comment by Byrom on March 19, 2015 at 11:28 pm

There is a saying in the black community that color trumps integrity. Martin Luther King Jr. longed for a day when a person would be judged by the content of his character and not by the color of his skin. Unfortunately, “black” has become a victim class that can do no wrong. In Ferguson, an “unarmed” black youth was shot by a white police offer who had been beaten by that person. All the officer wanted to do was ask Michael Brown to not walk in the street, but Brown assumed that the officer knew that Brown had just committed a crime. An unarmed person of the right size and temperament can beat a person to death with his bare hands. I find it reprehensible that some in the black community, plus outside agitators, will riot over alleged white-on-black crime, but every day tolerate black-on-black crime and black-on-white crime.

Churches have no business supporting and joining in this foolishness. I am a non-racist white church member, and I do not need anyone trying to tell me otherwise. I have always judged every person I meet based upon the content of his or her character, whatever the race or ethnicity of that individual. And I have taught my children the same lesson.