“A man should hear a little music, read a little poetry, and see a fine picture every day of his life, in order that worldly cares may not obliterate the sense of the beautiful which God has implanted in the human soul.”

― Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832)

In the spirit of this magnificent quote, I share with you “a little music” to inspire that “sense of the beautiful which God has implanted in the human soul”.

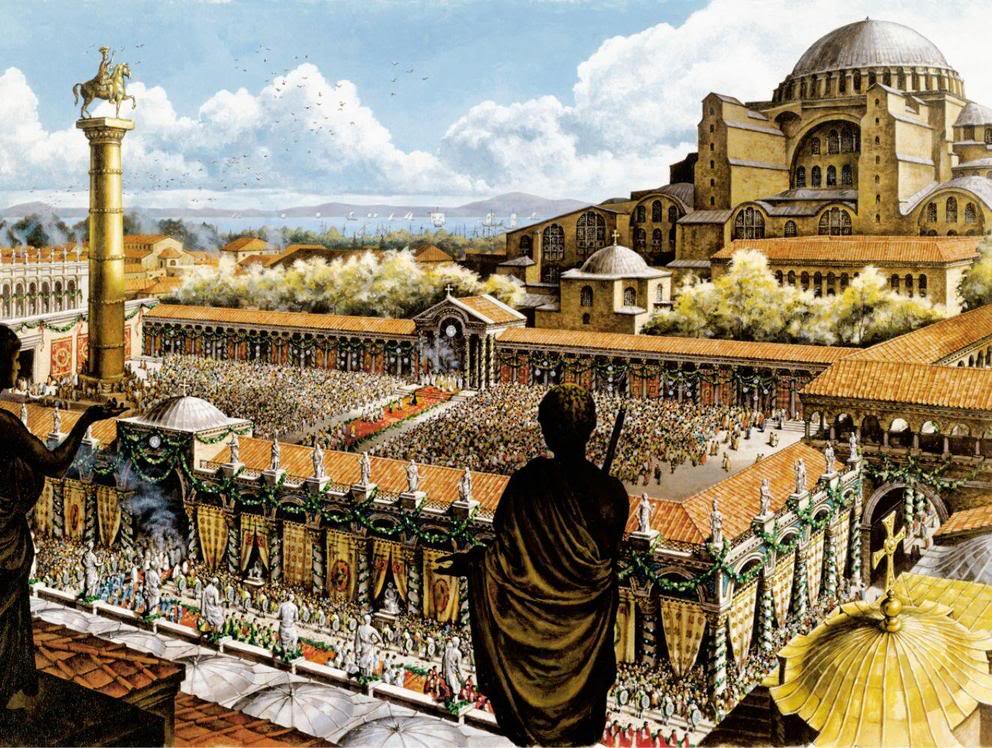

On May 29, Orthodox Christians worldwide remember the Fall of Constantinople to the forces of the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II Fetih (“the Conqueror”) on that date in 1453, over 560 years ago. Using the haunting text of Psalm 79, a survivor of the city’s brutal sack, Byzantine choralist Manuel Doukas Chrysaphes (Greek: Μανουὴλ Δούκας Χρυσάφης, active from 1440–1463) composed this profoundly transcendent lament for the fall of the Great City, the “Eye of the World”.

The Portland, Oregon-based Byzantine choral ensemble Cappella Romana sings this otherworldly lamentation. Here is an excellent review of Cappella Romana’s performance of the lamentation by The Oregonian’s Barry Johnson.

Most musical historians regard Manuel Chrysaphes as the most prominent Byzantine musician of the 15th century. He was a renowned singer, composer and musical theoretician who served as a master choralist at the courts of the last two Byzantine emperors, John VIII and Constantine XI. His surviving treatise, “On the Theory of the Art of Chanting” is an invaluable guide to Byzantine music and the evolution of courtly singing in the late Palaiologan period.

One of the most traumatic events in Christian history with lasting repercussions to this day for Greek-speaking people in particular, Constantinople’s fall to a multi-confessional, multi-ethnic army led by Sunni Muslim Turks was also one of the pivotal turning points in Western and Ottoman history.

While the city had declined in population, power and prestige to become a shadow of its former self, and was in fact little more than a series of loosely connected villages huddled behind the ancient Theodosian walls when Mehmed’s forces breached them, its fall came like the crashing of a giant in the Christian consciousness.

With the death of the Emperor Constantine XI on the walls of the city, the Empire whose citizens had simply called themselves ‘Romans’, whose official name was Βασιλεία Ῥωμαίων, the Roman Empire, or Ῥωμανία, ‘Romania’, came to an end after 1100 years. When one thinks of the city’s repeated attacks and sieges by the Huns, Persians, Arabs, then-pagan Vikings and Russians, Bulgars, Crusaders, Seljuk Turks, and finally the Ottomans, it is remarkable that, until its first sack by the Crusaders in 1204, Constantinople presided over an empire which achieved an extraordinary integration of three main influences: Greek culture, Roman political organization, and Eastern Orthodox, or ‘Byzantine’ Christianity.

Byzantium synthesized an extraordinary ancient cultural and philosophical legacy from classical Greece and the Hellenic kingdoms with that of Roman law, political theory and imperial government structure, preserving thousands of classical and legal texts which would have likely been lost in the West. Crucially, Constantinople’s endurance of many centuries of external pressure, including intermittent hostility with the northern Italian mercantile states after 1204, especially Venice and Genoa, served to prevent major Muslim expansion into Europe..

From an Orthodox Christian perspective, Constantinople’s stature as the patriarchate second in honor as the New Rome after the Old caused it to become the center of what came to be called Byzantine, or Greek, orthodox Christianity with a vast contribution in liturgical tradition, Patristic writings, homiletics, mystical theology, and spiritual phronema. The fall of Constantine’s City profoundly shocked all of Christendom, especially Rome, as the ancient patriarchate which had been second in honor in the Christian oikoumene was now transformed into the capital of the world’s most powerful Muslim empire which was to menace the Christian West for centuries.

For the Ottoman Turks, the conquest of Constantinople in 1453 marked the crowning inauguration of their hegemony in the eastern Mediterranean and their transformation from a powerful Turkish kingdom into a burgeoning world empire which had conquered the Second Rome and soon threatened all Christendom with a kind of reverse Crusade. They finally gained the prize which they had been encircling for over a century since their fourteenth century conquest of most of Anatolia and their expansion behind Constantinople into Thrace and Serbia.

From Constantinople, successive sultans began to expand Ottoman territory ever further into Central Europe, with the forces of Suleiman the Magnificent (1494-1566, r. 1520-66) only repulsed in 1529 after nearly conquering Vienna. Throughout the Ottoman empire, Turkish magistrates enforced the infamous devisherme system which exploited local Christian populations by forcibly conscripting numerous boys as janisarries (the sultans’ elite shock troops) or court eunuchs, and Christian girls for the imperial harem.

Within a century of overtaking Nova Roma on the Bosporus, Ottoman forces had conquered much of the Kingdom of Hungary, continuing to threaten the Habsburg-controlled Holy Roman Empire until the end of the seventeenth century when they last attempted to conquer Vienna. Unsurprisingly, historians traditionally date the end of the Middle Ages to the fall of Constantinople, from which they also mark the official opening of the Renaissance and the early modern era as Greek refugees poured into Italy.

Comment by Gabe on June 5, 2014 at 11:57 pm

The fall of Constantinople to Mehmet Fatih was an absolute shock to the rest of Christendom. While the Catholics and Orthodox acrimoniously split in 1054, there were many Venetian (and other European) Catholics led by the famed soldier Giovanni Giustiniani who were willing to stand with Emperor Constantine to defend the Turks. As formidable as the Turkish army was, with the relenting pounding of the walls by their massive cannons, the Greek defenders and their allies held out for 50 days, repairing walls as necessary, sallying out to repel attacks, and praying that assistance would come from Western European armies.

Ironically, before the light rose on Tuesday May 29th, 1453, it wasn’t the final push by Sultan Mehmet II’s men that overwhelmed the defenses and led to the city’s fall. In fact, the defenders held off the Turks to the frustration and desperation of the Sultan. The end came when someone had forgotten to relock the door of Kerkaporta on the northern edge of the city’s fortifications on the Golden Horn. A band of Turkish janissaries cautiously entered this unguarded door convinced it was a trap. Moving slowly into the city, they discovered that their entrance was a Greek oversight as nearly all of the defenders had locked themselves into a section in the central part of the wall to meet the attackers. The janissaries rushed up wall and planted the Turkish flags on the wall. While these flags were quickly taken down by a group of Greek troops, the sight of the enemies flags within the city melted the strength of the defenders who started to flee. Both Giustiniani and Emperor Constantine were killed in the rout.

Constantinople is long gone, and yet as Christians, there are lessons for us to learn out of it. We know that as followers of Christ, this life is like a battle. The apostle Paul commands us to put on our spiritual armor because we are not playing on a neutral playing field. This means that in our personal lives, our spiritual lives, and our societal lives, we must constantly guard our defenses. Yet those who mean us harm do not always attack from the front, but will hit us from a side where we were least expecting us. You think that you are seeing temptations in one area recede in your life and they hit you in another area. You know the sin in your life and face it head-on only to have an unexpected frustration/desire/temptation attack you. My prayer is that we are constantly asking God and other believers to show us the Kerkaportas in our life that we can always be fixing the defenses so that we can run the good race and fight the good fight.

If you are interested in learning more about the fall of Constantinople, pick up the book “1453” by Roger Crowley, you won’t put it down!

Comment by Jose Fernandez on April 15, 2015 at 12:58 am

The reply to this is KILL. Bring a new Crusade. AND i will gladly put the shield on. The muslims are heretics and should be killed, like they kill our Christian brothers. Revoke vatican 2, give me liberty against the infidelis.