“I am pleading against those principles that naturally tend to anarchy and confusion; that directly tend to unhinge all government, and overturn it from the foundation.”

Russell Kirk once named John Wesley, along with T.S. Eliot, as one of the great figures that succeeded in restoring the religious imagination of a people. Kirk said of these men that they moved “minds and hearts toward the transcendent again, opening eyes that had been sealed.”

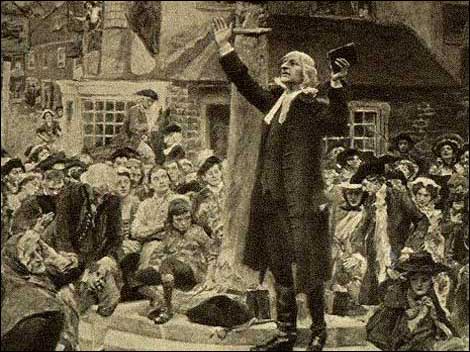

Wesley, of course, is known for sparking religious revival in both England and America. However, he also had a great deal to say about the politics of his time. He was a self described Tory, which to paraphrase his words, consisted in believing that men are to fear God and honor the King.

He once gave a concise introduction to his political beliefs by simply stating, “Now, I cannot but acknowledge, I believe an old book, commonly called the Bible, to be true. Therefore I believe, ‘there is no power but from God.’” It is important to remember that Wesley, like his contemporary Edmund Burke, lived in an age of revolution, when people were beginning to act on the belief that power originates with the human person. Wesley foresaw this belief leading to a morality based on consent, and noted, “It is allowed, no man can dispose of another’s life but by his own consent. I add, No, nor with his consent; for no man has a right to dispose of his own life. The Creator of man has the sole right to take the life which he gave. Now, it is an indisputable truth, none gives what he has not. It plainly follows that no man can give to another a right which he never had himself; a right which only the Governor of the world has.”

Even though Wesley’s political affiliations put him at odds with Edmund Burke, a Whig, Wesley struck what can only be described as a Burkean tone when he declared that others may “rejoice in the common rights of free men. I rejoice in all the rights of my ancestors.”

Furthermore, Wesley had a more classical understanding of liberty than most today. Put simply, liberty is doing what you ought, not what you want. In his tract Observations on Liberty, he extensively criticized the failure to distinguish between licentiousness and true liberty. Once again sounding a very Burkean tone, he concluded that no one has the right to break the laws of his own country. As long as man has the ability to work, enjoy the fruits of his labor, and serve God, then he is free. We improve our liberty “by devoting all we have, and all we are, to God’s honorable service.”

In a passage that is particularly offending to modern sensibilities, he derided the idea that “To be guided by one’s own will, is freedom; to be guided by the will of another, is slavery” as nothing more than “barefaced” ideology. He further asked, “If this is true, how free are all the devils in hell, seeing they are all guided by their own will! And what slaves are all the angels in heaven, since they are all guided by the will of another!”

Wesley’s continuing theme is that we must look higher than the individual with all his wants and passions. Man cannot be the source of his own goodness. Rather than deifying humanity, Wesley relied firmly on the doctrine of original sin in concluding that temperance and prudence must be the primary political virtues. He saw in England a rampant “epicureanism,” and knew that individual self-control is the foundation of public order. “Every glutton,” he predicted, “will, in due time, be a drone.” He also derided laziness, and noted that in previous generations Parliament would meet at five o’clock in the morning. Imagine how Congress would look if that were still a habit.

This understanding of liberty made Wesley largely unsympathetic to those who come into the public square claiming rights. The proper stance is to come accepting duties. Cicero believed that Piety was the foundation of all virtues. Similarly, Wesley believed “Impiety is the first and principal cause of our misery” Piety can be defined simply as being reverent or religious, but it is certain kind of reverence. It is reverence given to those things that are, by their nature, more excellent than we are. For the liberal and modernist, man is the measure in that there is nothing higher than human person. All things exist to serve man because there is nothing more excellent than he. In order for piety to even exist, we must recognize that there are many things more excellent than us. We may call these the transcendentals, the Natural Law, or simply God, from whom all excellence flows; yet the important thing is to humble ourselves enough to recognize that excellence makes demands on our lives even though we do not consent to it, and even though we cannot make demands on it in return.

Wesley did not shy away from condemning the evils of his day. Yet, he knew that true regeneration must begin at the individual level. Only the nation of pious individuals can be the good society, and for Christians, as always, this means leading by example. When we enter the public square, we must adopt that piety and humility that requires “each of us lay his hand upon his heart and say, ‘Lord, is it I?’”

Comment by exultnu on July 11, 2014 at 1:04 am

Excellent article Brian.