By Mark Tooley (@MarkDTooley)

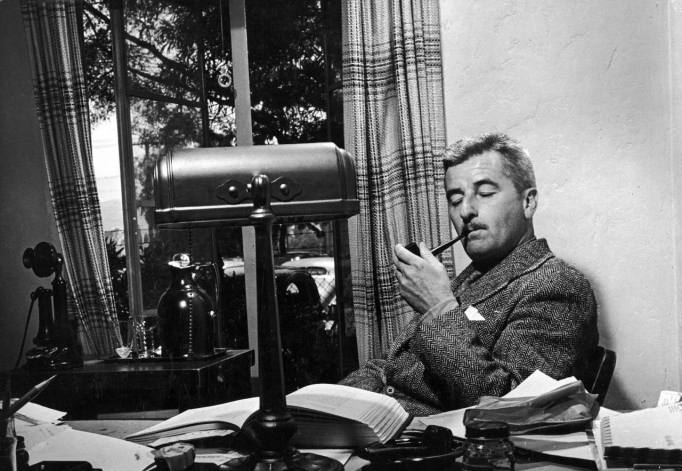

Sadly, Dean Faulkner Wells died last year shortly after publishing her delightful memoir about her uncle, famed Southern novelist William Faulkner. Every Day by the Sun: AMemoir of the Faulkners in Mississippi was favorably reviewed. It would be hard to write an uninteresting book about her colorful, eccentric family. She did several media interviews and then was felled by a stroke, age 75, appropriately expiring in the Mississippi Faulkner hometown of Oxford, which was the fictionalized backdrop for many Faulkner novels. Wells was partly raised by the Nobel and Pulitzer Prize winner, her father, William’s younger brother, having died before her birth in a plane crash. She assumed her uncle was long plagued by guilt, having given his brother the plane, which her father piloted in the 1930s as a stunt flyer for Southern rural audiences. Wells was the last of Faulkner’s immediate family, his daughter and step-daughter already deceased.

A recent visit to Oxford, home to the University of Mississippi, fulfilled expectations of a gentile courthouse town full of ghostly, Faulknerian memories. In Faulkner’s novels, it became the thinly veiled 19th century and early 20th century town of Jefferson, county seat to Yoknapatawpha County, where generations of Snopses, Bundrens, Sartorises, and Hightowers roamed across the pine studded landscape. Many of the characters were loosely or not so loosely based on Faulkner’s own family, ancestors, and neighbors. In her book, Wells laments the town’s recent gentrification, its charm and literary celebrity having made it a tourist destination and a home for well-heeled retirees. The town square still looks much as Faulkner would remember it, except there is a seated statue of him, plus an assortment of nouveau cuisine restaurants catering to a more upscale clientele. Wells remembered one New Year’s Eve when the one option for her family was a diner serving only cheeseburgers and peach pie. Doubtless frustrated by Oxford’s limited social, cultural, and dining choices, Faulkner in his later years lived part time in Charlottesville, Virginia. But he always returned to his antebellum home, Rowan Oak, in Oxford. The Confederate statue outside the court house, an iconic symbol of Southern timelessness in his novels, still looms over the town square.

Faulkner had his vices. As a young man and under-employed World War I veteran who never saw combat, he visited Memphis brothels, often accompanied by his underage younger brother, Wells’s father, who waited in the parlor while Faulkner was behind closed doors. He had numerous adulterous affairs with ever younger mistresses who revered and exploited Faulkner’s fame. He was also a frequent inebriate, frequently hospitalized across the decades for alcoholic excess. Wells claims she never saw him drunk. Faulkner seems to have been most of the time a thoughtful father and uncle. He drove the children to school, hosted their parties, paid for their travel and education, and presided over their weddings. Faulkner provided for not only the children but siblings, in-laws, and his long-lived mother, with whom Wells also lived. He was nearly always courtly to friends and strangers though was partly a social recluse who was indifferent to his celebrity. He brushed off a phone call from CBS journalist Edward R. Murrow once when Wells answered the phone. And he avoided Vincente Minnelli when the Hollywood director was filming a Faulkner story in Oxford. When Clark Gable professed not to know Faulkner was an author, he reciprocated by asking Gable’s profession. Wells recounts she did not appreciate her uncle’s fame until a movie based on his novel Intruders in the Dust, debuted at Oxford’s only movie theater. Faulkner attended the opening night but declined to address the audience. When a later Faulkner-based novel appeared on screen, he curtly told the audience it bore no resemblance to his work and walked out.

Faulkner seems not to have been conventionally religious. He was raised sort of Methodist, married in a Presbyterian church, and later became an infrequently church-attending Episcopalian. But intrinsically as a Southerner, religion permeated his works. His fictional religious characters were often absurd or despicable. Calvinists were especially mocked, and he liked to assert that there was no music in a Presbyterian hymnal. Rev. Hightower of his novelLight in August infamously is driven into seclusion by the predestinarianism of his faith, hauntingly obsessed with his grandfather’s role in a Civil War skirmish in Jefferson decades before his birth. But religion itself was for Faulkner enduring and inescapable. A sort of faith permeated his 1950 Nobel acceptance speech in Stockholm, where he insisted transcendent humanity would prevail against the threat of nuclear war.

Wells recounts her sadness when Faulkner died in 1962 at age only 65. The funeral was at Faulkner’s estate. Writer Shelby Foote afterwards joined Wells on the front porch, telling her of first knocking on Faulkner’s door as a stranger 30 years before, with a young and slightly embarrassed Walker Percy waiting in the car. Only a few months later in 1962, Oxford became globally infamous when thousands of rednecks descended on the University of Mississippi campus to prevent enrollment of the school’s first black student, James Meredith. Several hundred law enforcement officers and rioters were wounded in the ensuing riot, and two persons were killed. Wells watched and welcomed federal troops marching down the street. She also witnessed an elderly black man wrung from his car, which attackers then set on fire. Her uncle, she remembers, was the family’s nearly lone racial progressive, his novel Intruders in the Dust having foreshadowed To Kill a Mockingbird by featuring an innocent black man charged with a felony and under threat of lynching.

The 15th anniversary of Faulkner’s death and the Ole Miss riots over Meredith passed relatively quietly this year. Having dramatized in literature the old, pre-desegregation South for the whole world, Faulkner left this world just as a new more racially enlightened South was born. Wells doesn’t directly comment on the symmetry but must have recognized it. She died before enjoying the full reception of her book. But at least she survived to produce the final memoir about her uncle, the South’s most famous novelist.

Read the original article here. Also, follow the Institute on Religion and Democracy on Twitter! We are @TheIRD.

Comment by Mark on December 17, 2012 at 11:33 am

Wow! Did this article ever bring back memories for me. As a student at Emory University around 1980 I accompanied Faulkner biographer Floyd C. Watkins to Oxford in order to interview Faulkner’s nephew, Jimmy Faulkner. Jimmy showed us around Oxford, taking us to Rowan Oak, etc.

It was a fascinating trip, particularly in view of the fact that we had already read most of Faulkner’s novels and could see some of the inspiration for Faulkner’s narratives.

Thanks for this article. Supporting the IRD has multiple benefits!

Comment by TheLadyJournal on January 7, 2013 at 12:40 pm

I’m going through Faulkner right now and just read an amazing book regarding your comment! It’s called Above the Treetops by Jack Sacco. I encourage you to read it and it would bring back your own memories.

God Bless,